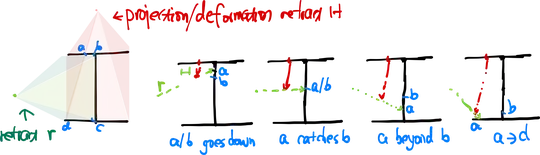

In the first pages of his "Algebraic Topology" book, Allen Hatcher describes a 2-dimensional subspace of $\mathbb{R^3}$, a box divided horizontally by a rectangle in two chambers, where the south chamber is accessible by a vertical tunnel (in green in the picture) obtained punching down a square from the ceiling of the north chamber, while viceversa the north chamber is accessible by a similar tunnel dug from the bottom of the box. Also, two vertical rectangles (in pink) are inserted as support walls as shown in the figure below:

Such space (we call it $X$) is contractible, and the author proves it in the following way (here $\simeq$ means homotopy equivalent and $=$ homeomorphic):

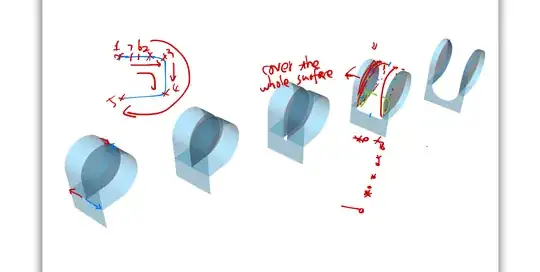

To see that $X$ is contractible, consider a closed $\epsilon$ neighborhood $N(X)$ of $X$. This clearly deformation retracts onto $X$ if $\epsilon$ is sufficiently small. In fact, $N(X)$ is the mapping cylinder of a map from the boundary surface of $N(X)$ to $X$. Less obvious is the fact that $N(X)$ is homeomorphic to $D^3$, the unit ball in $\mathbb{R^3}$. To see this, imagine forming $N(X)$ from a ball of clay by pushing a finger into the ball to create the upper tunnel, then gradually hollowing out the lower chamber, and similarly pushing a finger in to create the lower tunnel and hollowing out the upper chamber. Mathematically, this process gives a family of embeddings $h_t: D^3 \to \mathbb{R^3}$ starting with the usual inclusion $D^3 \hookrightarrow \mathbb{R^3}$ and ending with a homeomorphism onto $N(X)$. Thus we have $X \simeq N(X) = D3 \simeq point$ , so $X$ is contractible since homotopy equivalence is an equivalence relation. In fact, $X$ deformation retracts to a point. For if $f_t$ is a deformation retraction of the ball $N(X)$ to a point $x_0 \in X$ and if $r : N(X) \to X$ is a retraction, for example the end result of a deformation retraction of $N(X)$ to $X$ , then the restriction of the composition $r f_t$ to $X$ is a deformation retraction of $X$ to $x_0$.

With the help of a computer simulation, this link and some imagination, I think I might figure out a possible deformation retraction (towards the center of the box) for $N(X)$ (the "tick" box surrounding $X$):

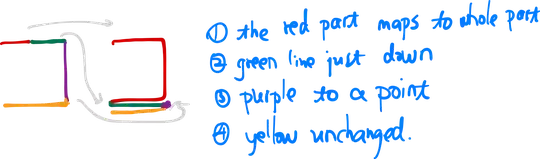

(1) Let take a first deformation retraction $f_1$ of the "tick" $\epsilon$ wall of $N(X)$ surrounding the rectangle $P1-P2-P3-P4$ that brings the segment $P4-P3$ onto $P1-P2$, leaving the faces of the vertical wall intact and digging a fissure in the middle of it, without tearing off the bottom of the wall below the segment $P1-P2$.

(2) Let's do a second deformation retraction $f_2$ on the same volume but now in the horizontal direction, so that point $P1$ is brought onto $P2$.

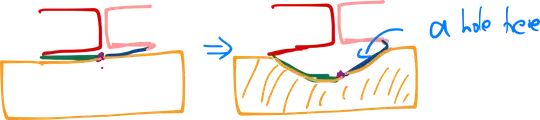

(3) Let's operate a third deformation retraction $f_3$ that now starts from the neighborhood of $P2$ and hollows a hole in the rigth wall of $N(X)$ towards the bottom, eventually developing a "free edge" from where the box can further collapse.

The same deformation retractions can happen on the other side of the box (for central simmetry) and from this point on what is left of $N(X)$ has some free faces enabling it to collapse on the central point.

First question then: is this sequence $f_1 \to f_2 \to f_3$ a correct deformation retraction for $N(X)$?

Here is my second matter. When it comes to consider, as suggested by the author, the composition $r \dot (f_1 \to f_2 \to f_3)$ restricted to $X$, I notice that during $f_1$ nothing happens to the structure of $X$, apart from $P3$ moving towards $P2$ and $P4$ moving towards $P1$, while portions of the ceiling in the $\epsilon$ neighborhood of $P4 - P3$ are mapped continously on the vertical pink wall. A similar behaviour appears during $f_2$, while $P1$ moves towards $P2$, but the vertical wall stays intact (at the end of $f_2$, we have that all the four points $P1, P2, P3, P4$ coincide, while the vertical wall is still intact and "made of" the images of points of $X$ belonging to the $\epsilon$ neighborhood of the rectangle). When $f_3$ finally starts, and the point $P2$ moves towards the bottom, a growing hole is produced in the external wall of $N(X)$, however the restriction to $X$ of the composition of such reformation retraction with $r$ produces a "hole" in the external wall of $X$ as well! Growing portions of the green segment to which $P1$ initially was belonging to are mapped (seemingly continously, as far as I can tell) on the border of the hole that is being produced in the external wall of $X$.

I'm not sure that the transformation I am describing is a correct homotopy, but if so, being it a deformation retraction of $X$ how can it be that a "hole" is produced in the external wall? Would not this imply that the homotopy type of the retracting space is changing? Where am I wrong?

Apologies for the long winded question, but I hope my points were clear and not too terribly distant from a rigorous approach.

thanks

- the hole that appears in the house may not be the hint that the homotopy type has changed, precisely because the whole set will later contract to a point. not every "hole" is responsible for non contractibility, see for instance a sphere with a point removed that happily contracts to a point.

– latelrn Jan 08 '22 at 10:14