Disclaimer: As a learner, I found this question confusing as well and was hardly satisfied with answers I could find. Then I posted an answer here myself, unfortunately that was wrong. But after deleting it and studying this again, I now have a better, even if lengthy, answer aimed at confused learners. Please let me know if there are still problems.

Clarification of question, intuition and sources

To clarify, in my book, it is formulated as:

Let $A, B$ be sets and $M_1$, $M_2$ $ \subseteq A$, as well as $N_1,N_2$ $ \subseteq B$. Let $f: A \mapsto B$.

Then it is asked, among other things,:

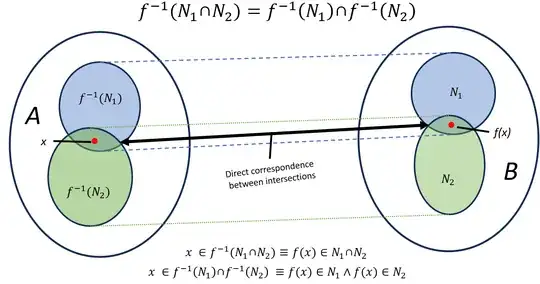

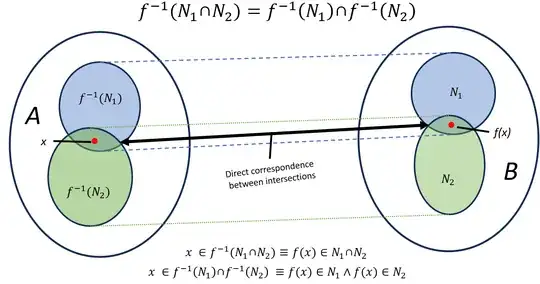

(1) Show $f^{-1}(N_1 \cap N_2) = f^{-1}(N_1)\cap f^{-1}(N_2)$

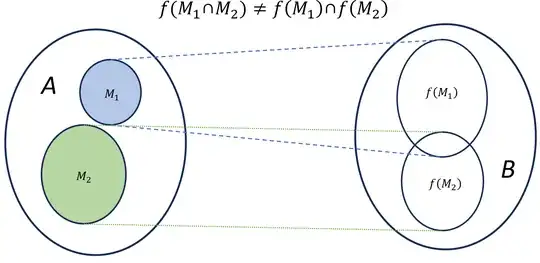

(2) Does in general also $f(M_1 \cap M_2) = f(M_1)\cap f(M_2)$ hold ?

Now, why does it hold for the inverse in (1) of $f$ but not $f$ itself in (2)? In (2) in this direction $\implies$ the domain is transformed through the map and you select an element $f(x)$ from $f(M_1 \cap M_2)$ so $x$ must be $ \in M_1 \cap M_2$ but the image of those two sets, when taken separately, might behave differently than the domain subsets. Hence you do not "know" yet what the map does to the elements and this is the exact problem you do not have with the inverse image where both intersections are predefined so to speak. I think it is easiest to understand through a couple of examples and visually. But first here are a few mathstackexchange links that clarify the question rigorously: A nicely written proof of (1). A proof of why (2) holds if and only if $f$ is injective.

First a counterexample with respect to (2)

We can easily construct a counterexample:

Let $A = \{1,2\}, B = \{3\}, M_1 = \{1\}, M_2 = \{2\}, f(1) = 3 = f(2)$.

Now here $f(M_1 \cap M_2) = \emptyset $ and $f(M_1) \cap f(M_2) = \{3\}$.

Note that this function specifically is not injective. And also note that still $f(M_1 \cap M_2) \subseteq f(M_1)\cap f(M_2)$ (here because $\emptyset$ is a subset of any set) but $f(M_1)\cap f(M_2)\nsubseteq f(M_1 \cap M_2)$.

Clarifying examples

Looking at the example we used as a counterexample above, we can observe that (1) still holds here because $N_1 = N_2 = \{3\}$ and so $f^{-1}(N_1 \cap N_2) = \{1,2\}$. Also $f^{-1}(N_1) = \{1,2\} = f^{-1}(N_2)$.

Let us take a look at another example.

Let $A=\{1,2,3,4\}$ and $B=\{a,b,c,d\}$ as well as $M_1 = \{1,2\}$, $M_2 = \{3,4\} \subseteq A$, as well as $N_1 = \{a,b\},N_2 = \{c,d\} \subseteq B$. Define $f: A \mapsto B$ via $f = \{(1,a),(2,d),(3,d),(4,d)\}$.

So all elements in $A$ are mapped to $d$ except $1$ to $a$. This function is clearly neither injective nor surjective. But (1) still holds. (2) is clearly violated again because $f(M_1 \cap M_2) = \emptyset \neq f(M_1) \cap f(M_2) = \{d\}$

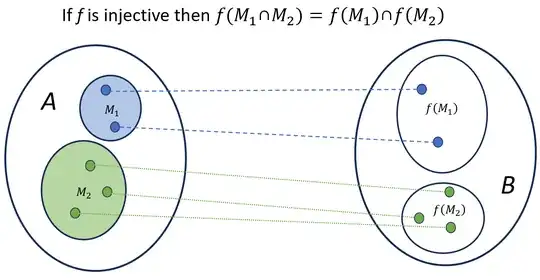

If however you had an injective function, (2) would hold. For instance adjust the counterexample so that you have an injective function by adding an element to the codomain and changing the map somewhat:

Let $A = \{1,2\}, B = \{3,4\}, M_1 = \{1\}, M_2 = \{2\}, f(1) = 3, f(2) = 4$.

Now here $f(M_1 \cap M_2) = \emptyset $ and $f(M_1) \cap f(M_2) = \ \emptyset$. So they are equal.

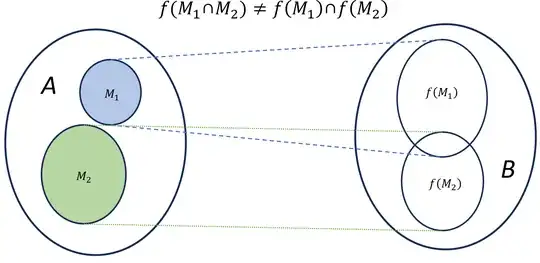

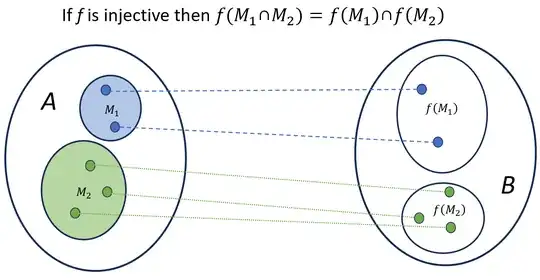

Schematics related to (2) and then (1)

First visualize a non-injective map.

Make sure you understand that if $f$ is injective (2) does hold.

In the inverse image if you select an element first from $f^{-1}(N_1 \cap N_2)$ or from $f^{-1}(N_1)\cap f^{-1}(N_2)$ does not matter since there is a direct correspondence or equivalence between these intersections (which is what you prove anyway of course). So in the end it comes down I think to really understanding the notation of the inverse image.