In integral domains, prove or give a counterexample:

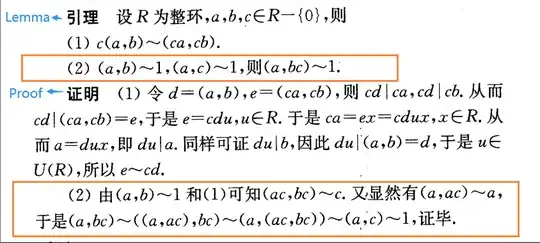

If $(a,b)\sim 1$, $(a,c)\sim1$, then $(a,bc)\sim1$.

That is to say, if $a,\,b$ are relatively prime and $a,\,c$ are relatively prime, then $a,\,bc$ are relatively prime.

Note that it needn't be a GCD domain. So usual proofs may not work here.

Any insights are much appreciated.

BTW:"$(a,b)$" is the abbreviation for "$\gcd(a,b)$" and "$x\sim y$" denotes the statement that $x$ and $y$ are associates. In integral domains, a gcd is often not unique when it exists. So "$(a,b)$" here denotes an arbitrary gcd of a and b. For the same reason, we use "$\sim$ " instead of "$=$".