I have the following system:

\begin{equation} f(x) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} A_n(x-n x_0) g(x-nx_0) \end{equation}

where system functions $A_n(x)$ are known, and I am trying to express output $g(x)$ in terms of the input $f(x)$. We may assume that $A_n(x) = 0$ for $n > N$, such that the summation consists of finitely many terms. Also, the range of $x$ of interest can be restricted to a finite interval.

However, I am having trouble trying to invert the expression to determine $g(x)$. This is what I have attempted so far:

I suspect the answer will take the form

\begin{equation} g(x) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} B_n(x) f(x+nx_0) \end{equation}

So, it looks like I want to determine what coefficients $B_n(x)$ are, and I believe these coefficients will be dependent only on the coefficients $A_n(x)$: If I change the input, I expect the output to change while $A_n(x)$ aren't changed. By symmetry in the target inverse expression, $B_n(x)$ should also not change, i.e. it is not dependent on the particular values of the input and output functions, but only dependent on $A_n(x)$. Please let me know if you think this assumption is incorrect.

By substituting one equation into another, we obtain

\begin{equation} f(x) = \sum_{j=-\infty}^{\infty}\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} A_j(x-jx_0) B_k(x - jx_0) \, f(x -jx_0 + kx_0) \end{equation}

We can use the Kronecker delta to compact this equation into

\begin{equation} \sum_{j=-\infty}^{\infty}\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} \Big(A_j(x-jx_0) B_k(x - jx_0) - \delta_{jk}\Big)\, f(x -jx_0 + kx_0) = 0 \end{equation}

$A_n(x)$ and $B_n(x)$ should not depend on the input, and so we can consider $f(x) = 1$ to get

\begin{equation} \sum_{j=-\infty}^{\infty}\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} A_j(x-jx_0) B_k(x - jx_0) = 1 \end{equation}

This is as far as I've got, but I feel like an appropriate choice of $f(x)$ might reveal more relationships between $A_n(x)$ and $B_n(x)$ that would allow them to be solved.

Simpler(?) case

If the general problem cannot be practically solved, then the case I am particular interested in is when $A_n$ is constant for $n \ne 0$:

\begin{equation} f(x) = A_0(x) g(x) + \sum_{n \ne 0} A_n g(x-nx_0) \end{equation}

UPDATE

In the paper

Sandberg, H., & Mollerstedt, E. (2005). Frequency-domain analysis of linear time-periodic systems. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 50(12), 1971-1983.

the concept of a Harmonic Transfer Function is used to relate functions of frequency that follow the same relationship as above. In the terms used in the question, an infinite dimension vector is defined, whose elements consist of a function that is incrementally shifted as one goes down the vector:

\begin{equation} \mathbf{f}(x) = \begin{bmatrix} \dots & f(x+2x_0) & f(x+x_0) & f(x) & f(x-x_0) & f(x-2x_0) & \dots \end{bmatrix}^T \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \mathbf{g}(x) = \begin{bmatrix} \dots & g(x+2x_0) & g(x+x_0) & g(x) & g(x-x_0) & g(x-2x_0) & \dots \end{bmatrix}^T \end{equation}

That is, we have vectors whose elements are defined as $f_n(x) = f(x-nx_0)$, and $g_n(x) = g(x-nx_0)$, where $-\infty < n < \infty$.

Therefore, we can express the following:

\begin{equation} f_j(x) = \sum_{j = -\infty}^{\infty} A_{jk}(x) g_k(x) \end{equation}

where $A_{jk}(x) = A_{k-j}(x-kx_0)$. That is, we an infinite linear matrix equation:

\begin{equation} \mathbf{f}(x) = \mathbf{A}(x) \mathbf{g}(x) \end{equation}

Now, this looks like something we can invert:

\begin{equation} \mathbf{B}(x) = \mathbf{A}^{-1}(x) \quad\text{such that}\quad \mathbf{g}(x) = \mathbf{B}(x) \mathbf{f}(x) \end{equation}

where $B_{jk}(x) = B_{j+k}(x-jx_0)$.

However, we have two problems: the matrix elements are functions of $x$, and the vectors and matrix are of infinite dimension! Is there a practical way to invert an infinite matrix, and would the inversion need to be done separately for each individual value of $x$? I get the feeling it might be possible to choose a matrix that is large enough, and it would be sufficient to invert that.

Numerical example

For the simplest case where $A_n(x) = A_n$ (i.e. constant), then $A_{jk} = A_{k-j}$. Let's consider the following example:

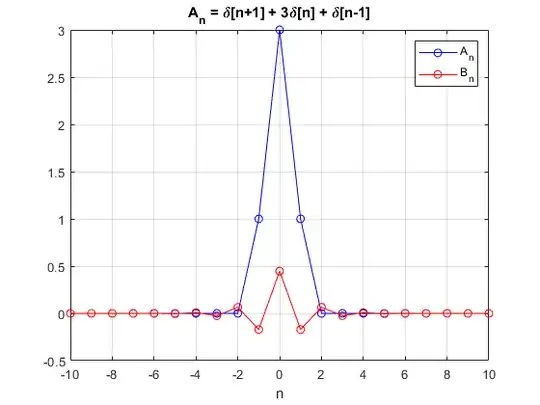

\begin{equation} A_n = \delta[n+1] + 3\delta[n] + \delta[n-1] \end{equation}

where

\begin{equation} \delta[n] = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{for $n=0$}\\ 0 & \text{for $n\ne 0$}\\ \end{cases} \end{equation}

That is,

\begin{equation} f(x) = g(x-x_0) + 3g(x) + g(x+x_0) \end{equation}

I obtain matrix $\mathbf{A}$, but I truncate it to a $201 \times 201$ matrix with the index ranging in $-100 \le n \le 100$.

Then I take the inverse of the matrix, and I extract the row at index $n=0$, which is $B_{0n} = B_n$. Using MATLAB to perform this inverse, I get

\begin{equation} B_{n} = \dots + 0.0652\delta[n+2] - 0.1708\delta[n+1] + 0.4472\delta[n]\\ - 0.1708\delta[n-1] + 0.0652\delta[n-2] + \dots \end{equation}

In other words,

\begin{equation} g(x) = \dots + 0.0652f(x + 2x_0) - 0.1708f(x + x_0) + 0.4472f(x)\\ - 0.1708f(x - x_0) + 0.0652f(x - 2x_0) + \dots \end{equation}

This appears to be what I want. Furthermore, it seems to show no discernible change whenever I increase the size of the matrix at truncation.

This is good, but I feel like this is still going to be quite clunky for the case where $A_0(x)$ is a function while $A_n$ is constant for $n \ne 0$. I don't want to have to invert a matrix for every value of $x$! Is there a way to extend the above numerical case to this slightly more complex case?

Aside

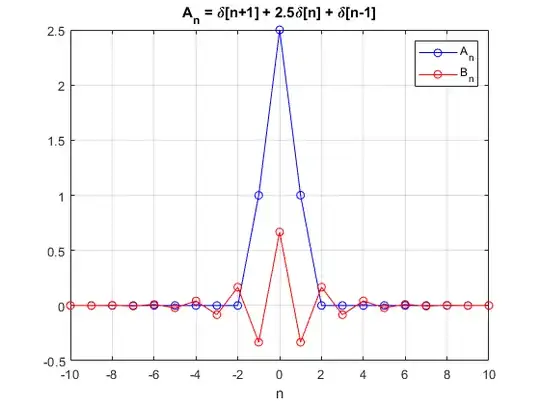

Interestingly, if I change the value of $A_0$ from 3 to a different value $m$, we get some interesting behaviour...

For $m = 2.5$:

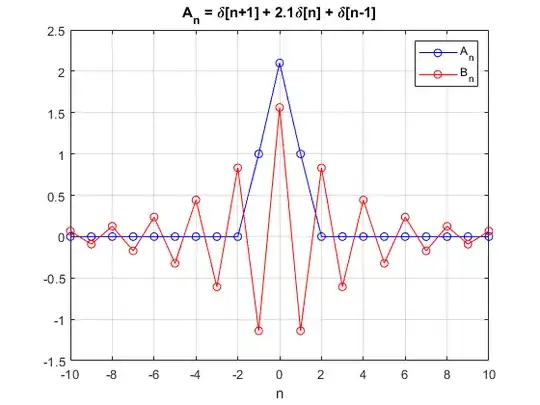

we see how the $B_n$ coefficients remain large over a larger span of index $n$. This is particularly noticeable for $m=2.1$:

As long as the coefficients drop off to zero before getting to the "edge" of the matrix, I think it is reasonable to assume these coefficients are the inverse that I'm looking for. However, for $m=2$, the coefficients do not die down sufficiently fast, only reaching zero right at the edge, and we see that the height of the coefficient $B_0$ is on the order of the size of the matrix:

If fact, $B_0$ seems to scale in proportion to the size of the matrix, suggesting that the untruncated infinite matrix would cause $B_n$ to blow up to infinity. This suggest certain systems of equations are singular, and cannot be inverted...