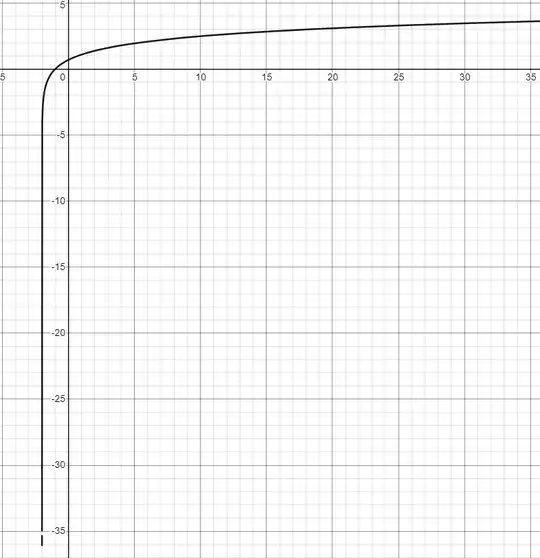

Let's assume you mean $y = f(x) = \log(x+2)$, so that at $x = -2$ the function is undefined and $\lim_{x\rightarrow -2^+} f(x) = -\infty$.

In reality, $f(x)$ is a continuous and in fact surjective function, meaning that every $y$-value is obtained by some $x$. This means a perfect drawing should have no gap as you notice.

However, for very large negative $y$, the solution to $y = f(x)$ will be very close to $-2$. For example, for $y = -15$, we solve $-15 = \log(x+2)$ to get $x = e^{-15}-2 = -1.99999969\ldots$; this means that the solution to $f(x) = -15$ will likely not be found by a grapher. Assuming that the grapher functions by plotting points $(x, f(x))$ for $x$ uniformly spread on a grid, ie $x = a + k(b-a)/n$, where $a$ and $b$ are the left and rightmost end-points and $n$ is the number of points to be drawn, and assuming $a$ and $b$ are integers, we would not be near such a point unless $n$ is on the order of $1/ .0000003059 \approx 3$ million values. In other words, when plotting the points $(x, f(x))$, the grapher doesn't see any value of $f(x)$ near $-15$ and so does not plot any such point simply because the granularity of is the chosen $x$ values to plot not fine enough. For example, the algorithm might graph the function based on a table like

\begin{align*}

(-2.01, \text{undefined}) \\ (-2, \text{undefined}) \\ (-1.99, -5.6\ldots)\\

(-1.98, -3.91\ldots )\end{align*} which skips over

$$(-1.99999969\ldots, -15)$$ entirely.

Of course, if some more sophisticated plotting algorithm is used this argument does not apply; I don't know about other curve-drawing algorithms so I will not venture a guess in that case.