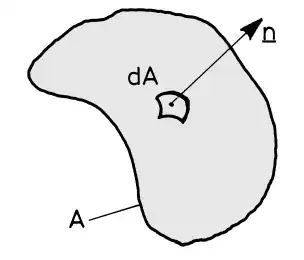

I consider a closed area $ A $ and a piece of area $dA$ from it. Now let be $ \underline{n} $ the normal vector of $ dA $. Then we call $ d\underline{A}:=\underline{n}\cdot dA $ the area vector.

Now here are my problems:

1.) I don't see why $ \oint d\underline{A}=\underline{0} $.

2.) I struggle with this weird notation just writing the symbol $ d\underline{A} $ into to this integral. I'm used to use this notation like this for example $ \int f(x)\space dx $.

3.) Is there some (physical) interpretation for the integral $ \oint d\underline{A} $ ?