The following text describes a construction of the unit sphere $\mathbb{S}^{3}$.

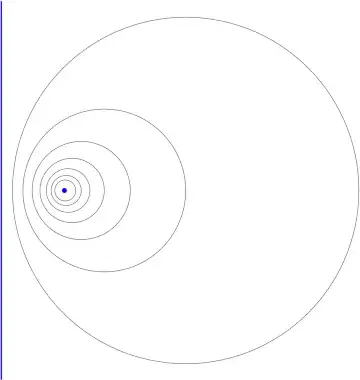

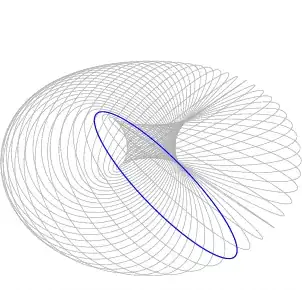

To consider the next example, it is helpful to practice visualizing $\mathbb{S}^{3}$ as consisting of two "polar" great circles $\{(z,0): z \in \mathbb{S}^{1} \subset \mathbb{C}\}$, $\{(0,w): w \in \mathbb{S}^{1} \subset \mathbb{C}\}$, together with a family of nested Clifford tori interpolating between them. Thinking of $\mathbb{S}^{3}$ as the unit sphere in $\mathbb{C}^{2}$, these Clifford tori are $$ T_{\alpha}:=\left\{(z \cos \alpha, w \sin \alpha): z, w \in \mathbb{S}^{1} \subset \mathbb{C}\right\} $$ for $\alpha \in(0, \pi / 2)$. (Note that $T_{\alpha}$ is the set of points at spherical distance $\alpha$ from the circle $\{(z, 0)\} .$ ) If we stereographically project to $\mathbb{R}^{3}$, then the two circles become the $z$ -axis and the unit circle in the $x y$ -plane, while the nested tori $T_{\alpha}$ grow around the circle and shrink around the line.

I’ve been trying but could not visualize how the two circles and the Clifford tori describe $\mathbb{S}^3$. Is there an equivalent construction for $\mathbb{S}^{2}$?

The picture provided with the text looks similar to the last one in this answer. However the process described there is also not clear to me. What is the relationship between $\mathbb{S}^{3}$ and two solid tori?