Consider the following process. For each integer $i \geq 0$, independently sample a Bernoulli distribution with probability $p = 1/2$, obtaining sample $x_i$. Then calculate $x = \sum_{i=0}^\infty x_i \theta^i,$ where $(\theta < 1)$. What is the distribution over $x$?

I see that if θ = 0.5 then this is a uniformly generated binary number between 0 and 2. This post is closely related, but I don't see how the method given there (with θ = 0.5) generalizes to arbitrary $\theta$. I am interested in values of $\theta$ close to 1, such as $\theta = 0.95$.

I am ultimately interested in a hypothesis test: $H_0=$ "$p = 0.5$" against the alternative $H_A=$ "$p \neq 0.5$". The motivation is, I am receiving an infinite sequence of 0s and 1s for which I only retain an exponentially weighted average (not recording the whole sequence). And based on this weighted average I want to decide whether the 0s and 1s were generated with equal probability or not.

Edit: based on an empirical test it appears to be roughly normally distributed. The following was generated by performing a 100,000 sample run with $\theta = 0.95$. It has mean 10 and variance 2.5.

5.9

6.0

6.1 *

6.2 *

6.3 *

6.4 *

6.5 **

6.6 **

6.7 **

6.8 ***

6.9 ***

7.0 ****

7.1 *****

7.2 *****

7.3 ******

7.4 ******

7.5 ********

7.6 ********

7.7 *********

7.8 *********

7.9 **********

8.0 ************

8.1 ************

8.2 *************

8.3 **************

8.4 ***************

8.5 ****************

8.6 *****************

8.7 ******************

8.8 *******************

8.9 *******************

9.0 ********************

9.1 *********************

9.2 **********************

9.3 ***********************

9.4 **********************

9.5 ***********************

9.6 ***********************

9.7 *************************

9.8 ************************

9.9 ************************

10.0 ************************

10.1 ************************

10.2 *************************

10.3 ************************

10.4 ***********************

10.5 ***********************

10.6 **********************

10.7 ***********************

10.8 **********************

10.9 *********************

11.0 *******************

11.1 *******************

11.2 ******************

11.3 ******************

11.4 ****************

11.5 ***************

11.6 ***************

11.7 *************

11.8 ************

11.9 ************

12.0 ***********

12.1 **********

12.2 *********

12.3 ********

12.4 ********

12.5 *******

12.6 ******

12.7 *****

12.8 *****

12.9 *****

13.0 ****

13.1 ***

13.2 ***

13.3 **

13.4 **

13.5 **

13.6 *

13.7 *

13.8 *

13.9 *

14.0

14.1

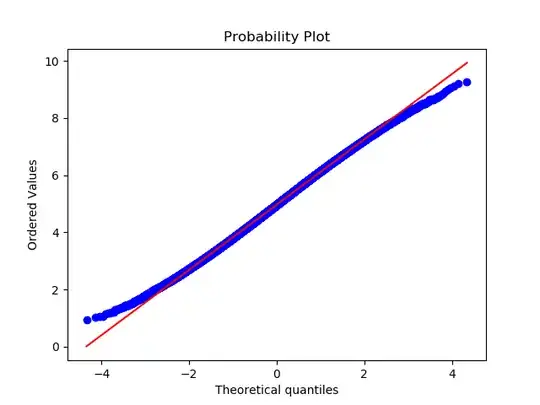

Normal quantile plot for $\theta=0.90$:

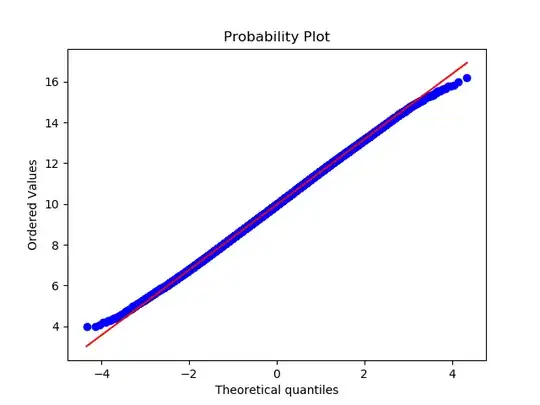

Normal quantile plot for $\theta=0.95$:

Normal quantile plot for $\theta=0.95$:

Looks like it has thin tails.