Let a real-valued function $f$ be continuous on $[0,1].$ Then there exists a number $a$ such that the integral $$\int_0^1\frac 1 {|f(x)-a|}\, dx $$ diverges. How to prove that statement?

-

: whats source? – M.H Jun 01 '13 at 10:13

-

10@Maisam Hedyelloo: The human mind. – user64494 Jun 01 '13 at 10:25

-

1There might be two cases of interest. 1) when $f$ vanishes on $(0,1)$; and 2) when it does not. If it does vanish, pick $a=0$ and the integral should diverge. If it does not, then pick $a=f(x_0)$ for some $x_0$ in $(0,1)$? – Cameron L. Williams Jun 01 '13 at 21:01

-

1Interesting question! I do not know the answer, but a counterexample must be quite pathological. – André Nicolas Jun 02 '13 at 02:43

-

f(0) and f(1) seem to work. – Abhimanyu Pallavi Sudhir Jun 07 '13 at 02:21

-

@CameronWilliams take $f(x) = \sqrt x$. It vanishes in zero yet $\int_0^1\frac{dx}{\sqrt x}$ exists. – TZakrevskiy Jun 07 '13 at 15:24

-

@TZakrevskiy I made the restriction that the zero lies on the interior for that reason. – Cameron L. Williams Jun 07 '13 at 18:09

-

@CameronWilliams All right, take $f(x)=\sqrt{|x-1/2|}$. By your suggestion take $a=0$, which yields a convergent integral. – TZakrevskiy Jun 07 '13 at 21:06

-

@TZakrevskiy after I wrote what I did, I realized my error. You're absolutely right. – Cameron L. Williams Jun 07 '13 at 21:18

4 Answers

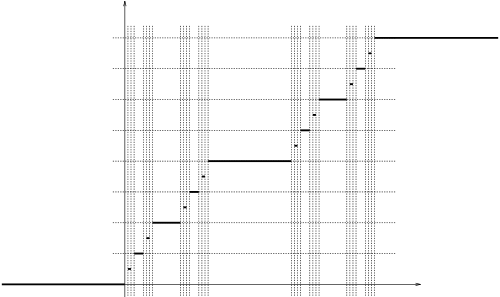

Take a nondecreasing rearrangement $r(x)$ of the function $f(x)$ (some discussion of this may be found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convex_conjugate). This involves finding a measure-preserving transformation of the interval $[0,1]$ that transforms $f$ into $r$. In particular, your integrals $\int_0^1\frac 1 {|f(x)-a|}\, dx$ are all preserved (for every $a$). Now apply the result that every monotone function is a.e. differentiable (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monotonic_function). Take a point $p$ where the function $r$ is differentiable. Then $a=r(p)$ does the trick, because $r(x)-a$ can be bounded in terms of a linear expression.

Note that the existence of a nondecreasing rearrangement of a function $f$ admits an elegant proof in the context of its hyperreal extension $^\star f$, which we will continue to denote by $f$. Namely, take an infinite hypernatural $H$ and consider a partition of the hyperreal interval $[0,1]$ into $H$ segments, by means of partition points $0, \frac{1}{H}, \frac{2}{H}, \frac{3}{H}, \ldots, \frac{H-1}{H}, 1$. Now rearrange the values $f(\frac{i}{H})$ of the function at partition points in increasing order, and permute the $H$ segments accordingly. The standard part of the resulting function is the desired monotone function $r$.

Note 1. I should point out that one does not really need to use the result that monotone functions are a.e. differentiable. Consider the convex hull of the graph of $r(x)$, and take a point where the graph touches the boundary of the convex hull (other than the endpoints 0 and 1). Setting $a$ equal to the $x$-coordinate of the point does the job.

- 47,573

-

What if the derivative is 0 at every differentiator point, as in the Lebesgue function of a cantor set? – Brian Rushton Jun 06 '13 at 14:14

-

1The constant functions are obvious counterexamples, so to make the problem meaningful in this case one could declare that the integral $\int_0^1 \frac{1}{0}dx$ "diverges". – Mikhail Katz Jun 06 '13 at 14:32

-

There are strictly monotonic functions whose derivative is 0 at every point where it is defined. – Brian Rushton Jun 06 '13 at 14:33

-

If one lets $a$ be the value of the function at that point, the integral $\int \frac{1}{f(x)-a}dx$ will indeed diverge. – Mikhail Katz Jun 06 '13 at 14:38

-

-

@ user72694: Why does the nondecreasing rearrangement preserve the Lebesgue measure? Could you give a reference? – user64494 Jun 06 '13 at 14:48

-

-

The formula for a nondecreasing rearrangement may be found here: http://math.stackexchange.com/questions/95277/nondecreasing-rearrangement-is-equimeasurable and as far as the integral is concerned, it diverges for the same reason that $\int \frac{1}{x}dx$ diverges near 0, as already discussed on this page. – Mikhail Katz Jun 06 '13 at 15:20

-

-

I was just pointing you to a formula which is given there. A reference for rearrangements is Lieb, Elliott H., & Loss, Michael (2001). Analysis (Second ed.). Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. There is a good discussion of this at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symmetric_decreasing_rearrangement – Mikhail Katz Jun 06 '13 at 15:33

-

-

It is not so simple. You use the relation $\int_0^1 \frac {1}{|f(x)-a|} dx = \int_0^1 \frac {1}{|f^*(x)-a|} dx.$ In order to base it, one can apply formula (3) on page 81 in the book you refer to (A copy of this page can be downloaded from RapidShare.). But formula (3) is valid if $\phi$ is of bounded variation. The function $\phi(t):=1/|t-a|$ does not possesses this property. Fortunately, there is a workaround: to take $\min(1/|t-a|,A)$ with big $A$. Without loss of generality one may assume $f$ to be positive. I accept the answer. – user64494 Jun 07 '13 at 04:41

-

@user64494: Thanks for the precise reference but I am unable to download from RapidShare. Would you happen to know on what page formula (3) can be found in the Russian edition of Lieb-Loss? – Mikhail Katz Jul 25 '13 at 07:04

-

The (nonstandard-analysis) tag is for questions that explicitly ask about NSA, (infinitesimals) if they mention infinitesimals but not NSA specific, and neither tag otherwise. If the answers use those concepts it does not affect the tagging of the question. – zyx Sep 03 '13 at 16:33

-

Here's a proof that $\int_0^1\frac1{\lvert f(x)-a\rvert}dx = \infty$ for every $a$ in the image of $f$ and outside of a meagre set. In particular, if $f$ is not constant, then there are uncountably many such $a$ in every neighborhood of the image of $f$. [Note: I also agree that user72694's proof works fine, and is completely independent of the proof I'll give here.]

First, define $g(a)$ to be the given integral, and let $[a_0,a_1]$ be the image of $f$. Assuming that $f$ is non-constant, we have $a_0 < a_1$. Letting $b_0 < b_1$ be in $[a_0,a_1]$ then Fubini's theorem gives, $$ \int_{b_0}^{b_1}g(a)\,da= \int_{b_0}^{b_1}\!\!\!\int_0^1\frac1{\lvert f(x)-a\rvert}\,dxda =\int_0^1\!\!\!\int_{b_0}^{b_1}\frac1{\lvert f(x)-a\rvert}\,dadx=\infty. $$ Here, the integral of $1/\lvert f(x)-a\rvert$ wrt $a$ is infinite whenever $f(x)$ is in $[b_0,b_1]$ (because $1/x$ is not integrable at the origin), which happens for $x$ in a nontrivial interval, so the double integral is infinite. This means that $g$ is not integrable (and, hence, is unbounded) in any nontrivial interval $[b_0,b_1]$ in the image of $f$.

Next, for each $K > 0$, set $S_K=\lbrace a\in[a_0,a_1]\colon g(a) > K\rbrace$. As $g$ is unbounded in the neighborhood of any point, the set $S_K$ is dense in $[a_0,a_1]$. Furthermore, $S_K$ is open for each positive $K$. To see this, note that $g_n(a)\equiv\int_0^11_{\lbrace\lvert f(x)-a\rvert > 1/n\rbrace}/\lvert f(x)-a\rvert dx$ is a sequence of continuous functions increasing to $g$, so $g$ is lower semicontinuous.

Hence, we have $$ \left\lbrace a\in[a_0,a_1]\colon g(a)=\infty\right\rbrace=\bigcap_{n=1}^\infty S_n, $$ which is a countable intersection of dense open sets in $[a_0,a_1]$ so, by definition, its complement is meagre.

- 34,429

-

-

Both answers to the question under consideration, which belongs to mathematical folklore and is authored by S. Konyagin, are right and nice. Unfortunately, I cannot share bounty between the two answers. – user64494 Jun 07 '13 at 04:55

-

2That's interesting. His wiki page that you linked does not say anything about the question. Can you elaborate? – Mikhail Katz Jun 07 '13 at 07:22

I don't think this statemnt is correct if $a\in[0,1]$. Maybe I'm wrong but you can take the counter example $f(x)=\frac 1 {|sin(x)+cos(x)|}$. So let's make two points: 1.looking at $|f(x)-a|$,notice that $f(x)=sin(x)+cos(x)$ is continious but moreover is nonegative. if $a\in[0,1]$ the integral is well defined. 2.Then the antriderivative of the function is wel defined according to maple and for all a in [0,1] the claim is correct.

EDIT: Let's try reductio ad absurdum and assume $\int_0^1 \frac 1 {|f(x)-a|} dx$ converges to $L\in\mathbb R$. Also let $a\in \mathbb R,f:[0,1]\rightarrow\mathbb R$. since the function is defined on a closed interval $\exists x_0 \in \mathbb R$ s.t $x_0$ is a maximum (concluding from weirestrass first lemma for continious function on closed intervals) . since $|f(x)-a|\leq |f(x_0)-a| \Longrightarrow \frac {1}{|f(x)-a|}\geq \frac {1}{|f(x_0)-a|}$. and taking $a\to f(x_0)$, $|f(x_0)-a|\to 0$ but then $ \frac 1 {|f(x_0)-a|} \to \infty$ and finally $L=\int_0^1 \frac 1 {|f(x)-a|}dx\geq \int_0^1 \frac 1 {|f(x_0)-a|}\to \infty$ which is undifined in contradiction for that we assumed that $L\in\mathbb R$.

-

2Thank you for the interest to the question. Unfortunately, you did miss the point. The statement does not assert that $a \in [0,1].$ – user64494 Jun 01 '13 at 10:04

-

-

Mmh i think there are some flaws in the proof (hope,that I'm not wrong) 1) You can't assert that exists $x_0$ s.t. $f'(x_0)=0$ only because f is defined on a close, maxima can be reach on the extremis of the interval and therefore the derivate is always $\neq 0$. Just take as counterexample $f(x)=x-\frac{2}{3}$. 2) the disequality about absolute value is not true in general, consider the previous $f$, if you take the maxima $=\frac{1}{3}$ and $a>0$ and a random point in $[0,\frac{2}{3}]$ you obtain a contradiction. – Riccardo Jun 01 '13 at 21:11

-

a. the derivative does not matter for the question. The important thing is you have a maximum (extreme value therom which is also explained here http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extreme_value_theorem). b. I don't think you can take the maximum from $[0, \frac 2 3]$ since you choose $x_0$ from $[\frac 2 3,1]$. if f is non-negtive the claim is correct. for the counter-example you wrote since the claim is correct in [\frac 2 3, 1],since the $\int_{\frac 2 3}^{1}$ diverges the whole integral divereges. For negitve function take $x_1$, the minimum of the function in almost a same way. – Jun 02 '13 at 02:28

-

If $x_0$ is a maximum for $|f(x)-a|$ then $a$ is (by implicit assumption) fixed, so you can't make $a\to f(x_0)$ and expect the inequality $|f(x) - a|\leq |f(x_0)-a|$ to continue to hold for all $x\in [0,1]$. – Nick Strehlke Jun 02 '13 at 02:42

-

That's not what I said: You have maximum/minimum of f, you take a in a close enough interval and than you get the desired result. or more clearly the method is: 1)you give me a continious f and I 2)Find maximum (minimum) in positive(negative) intervals 3)Take $a$ in a close enough interval. Hope it helps. If that's still not clear, give me one example it doesn't work. – Jun 02 '13 at 02:53

-

My point is that if $|f(x)|$ attains a maximum at $x_0$, then the inequality $|f(x) - a|\leq |f(x_0)-a|$ need not hold for all $x\in[0,1]$ unless $a = 0$. – Nick Strehlke Jun 02 '13 at 02:57

-

the maximum is for $f$ as I wrote twice. again, you still don't choose the a but only the x (statement is $\forall x\in[0,1] |f-a|\leq|f(x_0)-a|$ and NOT $\forall x\in[0,1]\forall a\in\mathbb R)$ $. for example you can't say that for $f(x)=x$, $|x-a|>|1-a|$since you choose only x. only after this level you choose the a. – Jun 02 '13 at 03:16

-

Are you not saying that ${1\over |f(x) - a|}\geq {1\over |f(x_0)-a|}$ as $a\to f(x_0)$ in order to conclude that $\int_0^1{1\over |f(x) - a|},dx \geq \int_0^1 {1\over |f(x_0)-a|},dx$ as $a\to f(x_0)$? What I'm getting at is that I don't see why these inequalities should be valid in the limit $a\to f(x_0)$. – Nick Strehlke Jun 02 '13 at 03:31

The Devil's staircase is a counterexample. When the integral is defined, it converges. For instance, at 0, the Devil's staircase is approximately between $(C_1 x)^{\frac{\ln 2}{\ln 3}}$ and $(C_2 x)^{\frac{\ln 2}{\ln 3}}$ (the curves connecting the left endpoints of intervals and right endpoints, respectively), and so your integral converges if $a=0$. Near any other point where the integral is defined, the integral converges since the set is self-similar, so all such points are like 0.

All of this is in Chapter four of Frank Jones' Lebesgue integration book, as well as pages 521.

- 13,375

-

-

-

4The constant functions are obvious counterexamples; so to make the problem meaningful in this case one could declare that the integral $\int_E \frac 1 0 dx$ over the set $E$ of positive measure diverges. This is a usual convention in real analysis. – user64494 Jun 06 '13 at 15:09