[...] It seems entirely trivial by comparison to the long chain of formal manipulations given as the solution, so I assumed it had to be faulty. [...]

The problem with your assumption is that formal proofs from scratch need to prove every single bit of the reasoning involved. In particular, how exactly do you justify that either "there is someone who is not asleep" or "there is not anyone who is not asleep"? Depending on your specific chosen formal system, this may be an axiom called LEM (law of excluded middle) or require a few lines of proof. Similarly, to get from the latter to "everyone is asleep" again may be allowed in one inference step or require some more lines of proof.

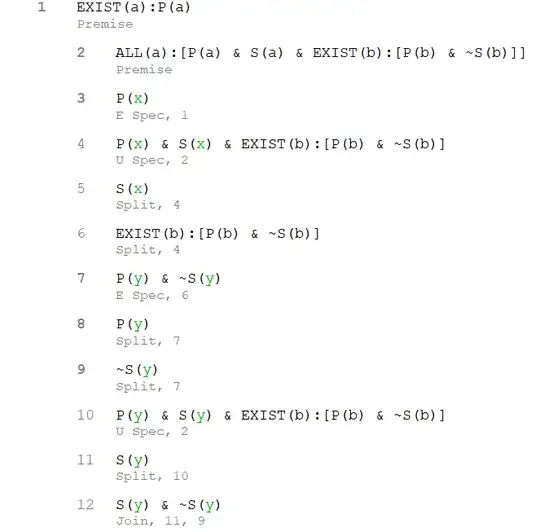

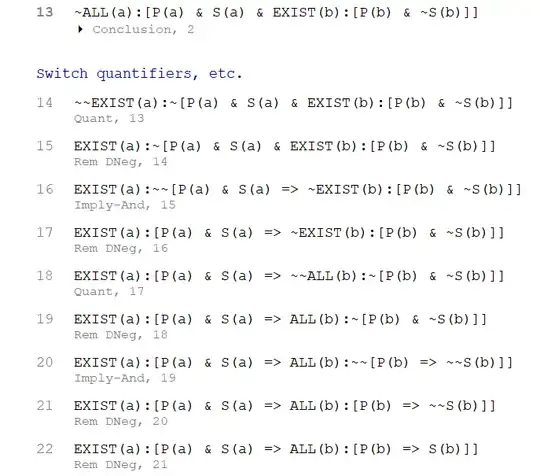

Here is a completely formal proof using a Fitch-style natural deduction system with LEM. The key to get an intuitive proof is to use LEM, so if the system does not support LEM then you simply prove the instance of LEM that you need! Shorter proofs in a formal system may be less intuitive.

If ∃x∈People: [✰]

∃y∈People ( ¬Asleep(y) ) ∨ ¬∃y∈People ( ¬Asleep(y) ). [LEM]

If ∃y∈People ( ¬Asleep(y) ):

Let c∈People such that ¬Asleep(c).

If Asleep(c):

Contradiction.

∀x∈People ( Asleep(x) ).

Asleep(c) ⇒ ∀x∈People ( Asleep(x) ).

∃a∈People ( Asleep(a) ⇒ ∀x∈People ( Asleep(x) ) ).

If ¬∃y∈People ( ¬Asleep(y) ):

Let d∈People. [from ✰]

If Asleep(d):

Given any x∈People:

If ¬Asleep(x):

∃y∈People ( ¬Asleep(y) ).

Contradiction.

Asleep(x).

∀x∈People ( Asleep(x) ).

Asleep(d) ⇒ ∀x∈People ( Asleep(x) ).

∃a∈People ( Asleep(a) ⇒ ∀x∈People ( Asleep(x) ) ).

∃a∈People ( Asleep(a) ⇒ ∀x∈People ( Asleep(x) ) ).

Important note: The statement in your question is actually not a logical tautology. As you should see from the above proof, it depends crucially on the assumption that there exists some person, otherwise it is trivially false.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Also, contrary to popular belief, the apparent paradox here is not really due to any mismatch between the English "if" and logical "if"! Rather, it is due to incorrect translation of the English sentence, due to the use of the generic present tense! Notice that the following sentence is actually true when interpreted according to standard English:

There is someone such that, if he or she is asleep at midnight on 16 Mar 2021, then everyone is asleep at midnight on 16 Mar 2021.

The problem with the original sentence was that because it used the present tense without a context specifying a single time, the time ended up being quantified outside the "if", and so it ended up being interpreted as:

There is a person A such that, at every time t, if A is asleep at time t, then everyone is asleep at time t.

Such implicit quantifiers do not go past explicit quantifiers, which is why it did not go all the way to the outside. Note that the logical tautology corresponds precisely to that:

At every time t, there is a person A such that, if A is asleep at time t, then everyone is asleep at time t.

I hope this partly linguistic explanation satisfies your inquiry into the apparent paradox, and yes as you guessed it is a quantifier swap, though not quite involving sleep-states but involving time. On the other hand, be aware that in general it is difficult to set down any rules to translate English into logical form. After all, there are still many people who insist on saying "All that glitters is not gold." instead of "Not all that glitters is gold."...