I'll use the Schoenflies Theorem: If $J_1$ and $J_2$ are Jordan curves in the plane (or sphere) there is an ambient plane (resp. sphere) isotopy sending $J_1$ to $J_2$. This is sometimes called the "strong" Schoenflies Theorem (it's a consequence of the Annulus Theorem). Let $\text{Int}(J)$ and $\text{Ext}(J)$ denote the bounded and unbounded complementary regions of $J$, respectively.

If $J_1, \dots, J_n$ are a collection of mutually disjoint Jordan curves, then call the collection simple if no $J_i$ is contained in any $\text{Int}(J_k)$. By induction and repeated use of the Schoenflies Theorem:

Observation 1: Any two simple collections of Jordan curves are ambient

isotopic if they have the same number of elements.

A continuum (plural continua) is a compact, connected metric space. We need the following theorem: A nested intersection of continua is a continuum, as proved in the body of the question here. Relevant is that since the Cantor Set is totally disconnected, it doesn't contain a non-degenerate continuum.

Let $B_\epsilon(x) = \lbrace y: |x-y| \leq \epsilon \rbrace$ and let $B_\epsilon(X) = \cup_{x \in X} B_\epsilon(x)$. If $X \subset \mathbb{R}^2$ is a continuum then let $X_\circ$ denote the filled in continuum obtained by adding each bounded component of its complement (it's a continuum since its complement is open and a sufficiently large disc around $X$ has the boundary bumping property).

Lemma 1: Let $C_1$ and $C_2$ be disjoint Cantor sets in the plane (or sphere).

Then there is a simple pair of disjoint Jordan curves $J_1$ and $J_2$

with $C_i \subset \text{Int}(J_i)$.

Proof: By Observation 1, it's sufficient to show that there are simple collections $\mathcal{A}_1$ and $\mathcal{A}_2$ containing $C_1$ and $C_2$ respectively such that $\mathcal{A} = \mathcal{A}_1 \cup \mathcal{A}_2$ is also simple, since in this case it is explicitly constructible after suitable isotopy. Since each $C_i$ is compact each $B_\epsilon(C_i)$ is a finite cover by Euclidean discs and thus each complementary component is a Jordan domain (apart from the unbounded one).

Letting $\epsilon$ be small enough that $B_\epsilon(C_1) \cap B_\epsilon(C_2) = \varnothing$, we get disjoint covers of each such that filling in their components produces covers by Jordan domains. However, it's possible that for some components $D$ of $B_\epsilon(C_1)$ and $E$ of $B_\epsilon(C_2)$, we have $D_\circ \cap E \neq \varnothing$, without loss of generality. In which case $E$ is contained in a complementary region of $D$ since it's disjoint from it.

In $D$, find a $\delta$ sufficiently small so that $E$ is no longer contained in any complementary component of $B_\delta(D \cap C_1)$. If none such existed, then for $\delta_n = \frac{1}{n}$ we have that $E$ is contained in a bounded complementary component of each $B_{\delta_n}(D \cap C_1)$, say of component $D_n$ respectively which are nested by construction. But this is impossible since it would imply the existence of a non-degenerate continuum in $C_1$, as $D_n$ cannot converge to a point while all separate $E$ from $\infty$ unless $D_n \rightarrow E$, but $D_n \subset D$ which is disjoint from $E$ and closed.

After doing this in each component of $B_\epsilon(C_1)$, by finite descent we have a simple collection $\mathcal{A}_1$ of Jordan curves with interior domains covering $C_1$ such that none intersect $C_2$, nor do their interiors. Doing the same for $B_\epsilon(C_2)$ produces the desired family $\mathcal{A}$. QED

Let $C$ be the standard Cantor ternary set, viewed as a subset of the real line $\mathbb{R} \times \lbrace 0 \rbrace \subset \mathbb{R}^2$. Let $E$ denote the set of endpoints of the (bounded) deleted intervals in the real line, and let $E_n$ denote the endpoints of the intervals with length $\frac{1}{3^n}$, called the $n$th level of $E$. Note that $E$ is dense in $C$. Call the removed intervals $U_j^n$ the $n$th level of removed intervals. Call the $2^n$ neighborhoods $D_j^n$ complementary to the $n$th level of removed intervals the $n$th levels of $C$. Note that the collection $\mathcal{D}_n = \lbrace D_j^n \rbrace$ is a covering of $C$ for every $n$, and each $D_j^n$ is a Cantor set that's clopen in $C$.

Let $I = [0,1]$ be the unit interval. If $X, Y \subset \mathbb{R}^2$ and $f: X \rightarrow Y$ is a homeomorphism, we say that an ambient isotopy $F: \mathbb{R}^2 \times I \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2$ extends $f$ if we have that $f(X) \equiv F(X \times \lbrace 1 \rbrace)$.

Theorem: If $C_1, C_2$ are Cantor sets in the plane and $f: C_1 \rightarrow C_2$ is a homeomorphism, there exists an ambient plane isotopy extending $f$.

Note that the proof below also works for the sphere.

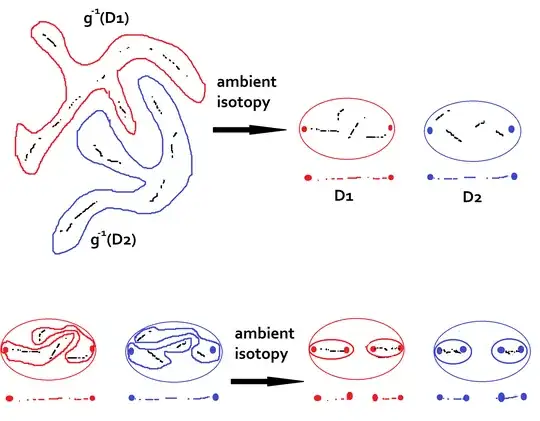

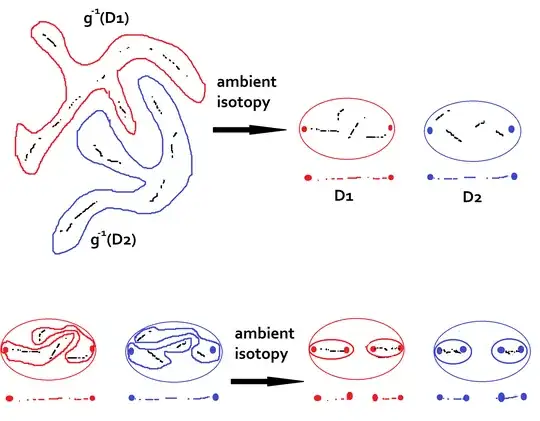

Proof: Let $g$ be an arbitrary homeomorphism from $C_1$ onto $C$, the standard ternary Cantor set. We produce an ambient isotopy from $C_1$ to $C$ extending $g$. Then there also exists isotopies extending arbitrary homeomorphisms $C_2 \rightarrow C$, and homeomorphisms between compact metric spaces are quotient maps. Thus we may factor $f$ through $g$ to obtain an $h^{-1}$ such that $f = h^{-1} \circ g: C_1 \rightarrow C_2$, a concatenation of ambient isotopies and thus an ambient isotopy itself.

By Lemma 1 and Observation 1 there is a simple pair of Jordan curves $J_1, J_2$ around $g^{-1}(D_1^1)$ and $g^{-1}(D_2^1)$, and these may be isotoped to narrow discs sitting above $D_1, D_2$ as shown below such that the preimages of the first level of $E$ share $x-$coordinates with their images. The interior of each is homeomorphic to the plane, so by induction we may apply Lemma 1 and Observation 1 repeatedly to isotope inverses as necessary to approximate $g$ on $g^{-1}(E)$. By concatenating isotopies which differ on uniformly smaller sets, we obtain a homotopy on the plane sending $C_1$ to $I$ and which is a homeomorphism for all $t < 1$. We need to show it's a homeomorphism at $t = 1$ on $C_1$, as it is clearly bijective off of $C_1$.

Since $g$ is a homeomorphism, $g^{-1}(E)$ is dense in $C_1$ so it uniquely determines the function $F$ restricted at time $t = 1$. Since both are compact metric spaces it's sufficient to show that $F$ is bijective on $C_1$ at $t = 1$. But this is immediate by construction, since any two points in $C_1$ are contained in disjoint elements of some $n$th level of $C$ and these have images with distance bounded below by $\frac{1}{3^n}$. QED

In higher dimensions the proof breaks down at the observation.

Anyone see how to continue to grab the Moore-Kline result?