I do not understand the end of Theorem 29.9, on pages 273-4 in Steven Lay's Analysis with an Introduction to Proof (4th edn 2005).

U(f) ≤ U(f,P) < L(f,P) + ε ≤ L(f) + ε

And then it says: "Since ε > 0 is arbitrary, we must have U(f) ≤ L(f)". I don't have any trouble understanding the rest of the proof but I don't understand how we get from the inequality above to U(f) ≤ L(f). Can someone explain to me the reason why we can remove ε and get to U(f) ≤ L(f)?

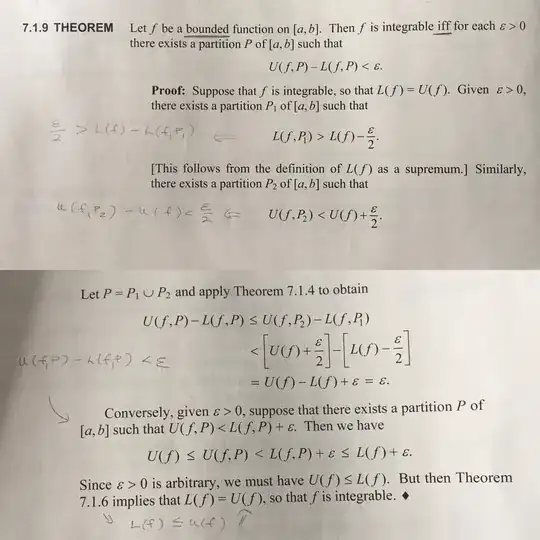

I've added a picture of the full proof to make it easier to understand my question.