I'm the OP, and I now kind of know what was causing me confusion back then.

I was actually thinking of function in a more computer science way. When we use the notation $y = f(x)$ in programming languages, it actually functions in the same way as I described in the question above. It first calculates $f(x)$ with the input $x$ and then stores the result into a temporary variable, and it then assigns the value of the temporary variable to the variable $y$. It does have two transitions in the process.

Yes, of course one can argue that function in mathematics doesn't need to have the same definition as function in programming languages. I agree, even though it is really weird to have two different definitions describing the same concept. But it is actually worthwhile to talk about which of them is more appropriate and more intuitive.

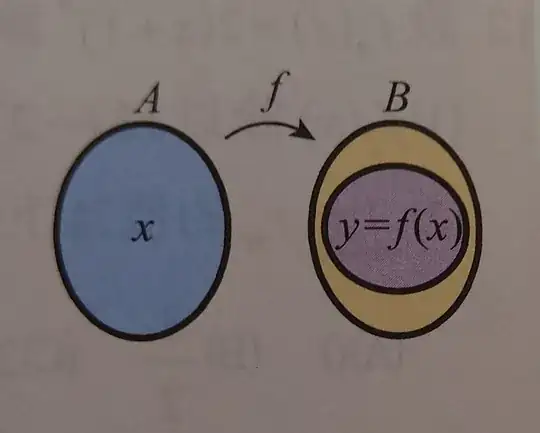

If we redefine function in mathematics in a more computer science way. We can define a function as $f: I → O$ , where $f$ maps the input $x$ in the domain $I$ to the output $f(x)$ in the codomain $O$. Defining function in this way makes a much more elegant expression, which would get rid of the redundant usage of $y$ which just means the same as $f(x)$. Confusion in choosing which notation to use happens all the time, not only in choosing between $f(x) = ax+b$ or $y = f(x) = ax+b$ but also $dy/dx$ or $df(x)/dx$.

Moreover, if we look back to the definition of function in programming languages, this kind of redundancy just doesn’t exist at all, and it never caused any problem. The variable $y$ is not pre-defined in the function itself, and is actually only needed when we want to “store” the final result, not to “use” the result for further calculation. The “real” output of the function $f$ is $f(x)$, not $y$.

The variable y can still be used with function in mathematics, but now it should no longer be seen as part of the definition of function. The expression $y = f(x) = ax+b$ thus should be understood alternatively as simultaneous equations of $y=f(x)$ and $f(x) = ax+b$.

To conclude, I think the original definition is obviously outdated and flawed compared to the more modern one used in computer science. It deserves a refurbished definition as it has been a quite fundamental and frequently used concept in mathematics, hopefully urgently.