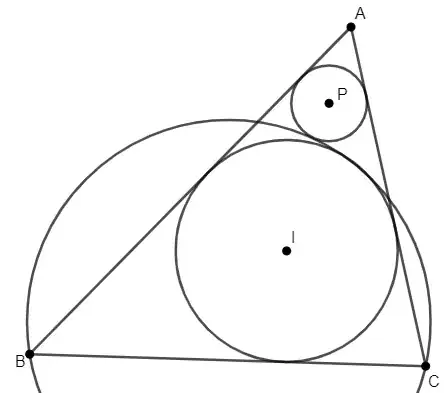

Given an acute triangle $\triangle ABC$ whose incircle is $I(r)$. Let $O(R)$ be the circle through $B$ and $C$ and which touches $I(r)$ interiorly. Show that the circle $P(p)$ which is tangent to $AB$, $AC$ and $O(R)$ (externaly) is such that one intagent line from $P(p)$ and $I(r)$ is parallel to side $BC$.

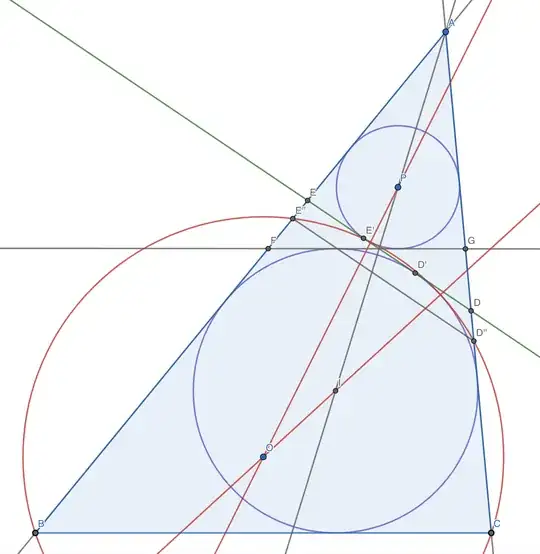

I have seen a couple solutions for this online but I never really understood them and they all seem wrong to me. For example, this is the problem 2 in here. The solution they give doesn't ring a bell. When they say that $\angle ACB - \angle ADE = \angle AED - \angle ABC$ (which is correct) and then they claim that $\angle ADE < \angle ACB$ and $\angle AED > \angle ABC$ imply that $\angle ADE=\angle ABC$ it just sounds wrong. They could just use the congruence of $ADE$ and $AFG$ but instead they use this confuse argument.

And things get worse after the co-axial system. They give a huge jump and conclude that $BCD'E'$ is cyclic. This is best solution I have found for this problem but I just can't agree with it.