Let $A$ be an $n×n$ complex matrix. Then there exists an invertible matrix $T$ such that $T^{−1}AT=J$ where $J$ is a Jordan form matrix having the eigenvalues of $A$. Equivalently, the columns of $T$ consist of a set of independent vectors $x_1, . . . , x_n$ such that $Ax_k=λ_kx_k$ , or $Ax_k=λ_kx_k+x_{k−1}$.

There exists an inductive proof by Filippov:

Base Case ($n = 1$): The Jordan canonical form of the matrix $[a]$ is $[a]$ itself.

Inductive Hypothesis: Assume the existence of a Jordan canonical form for all $r \times r$ matrices, $r = 1, 2, \ldots, n-1$, i.e., any $A_{r \times r}$ is similar to a Jordan matrix.

Now consider an $n\times n$ matrix $A$.

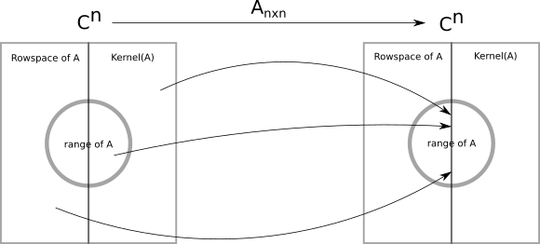

Assume $\lambda = 0$ is an eigenvalue, i.e., $A$ is singular. Therefore, the dimension of $C(A)$, the column space of $A$, is $r < n$.

The proof states: "By the induction hypothesis, $A$ (more precisely, the linear operator associated with $A$) restricted to its range has a Jordan canonical form."

What exactly does this statement mean in the context of the induction hypothesis?

My Thoughts:

Thanks to @ancientmathematician for pointing me in the right direction.

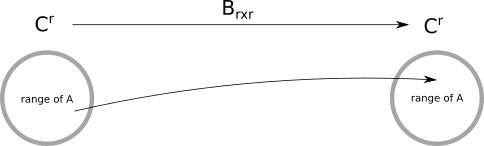

If we think of another tansformation, $T:range(A)\to range(A)$ and the corresponding matrix is $B_{r\times r}$ associated with it, then from the induction hypothesis there exists a Jordan canonical basis $(w_1,\cdots,w_r)$ for the $range(A)$ such that $Bw_k=λ_kw_k$ , or $Bw_k=λ_kw_k+w_{k−1}$.

However, the proof appears to use the same symbol $A$ for both the $n \times n$ matrix and the restricted $r \times r$ matrix $B$, which might be the source of confusion here.

Further Clarification Needed:

Even if that is the case, How can we extend the proof from here and find the conditions for the Jordan basis for the original $n \times n$ matrix $A$ ?

Specifically, how do we transition from: $Bw_k=λ_kw_k$ , or $Bw_k=λ_kw_k+w_{k−1}$. to $Aw_k=λ_kw_k$ , or $Aw_k=λ_kw_k+w_{k−1}$ for the original $n\times n$ matrix $A$ ?

Any insights would be greatly appreciated.

This proof is discussed in A Primer of Abstract Mathematics By Robert B. Ash.