The proof tacitly assumes that there is a function $sqrt:\mathbb{C}\rightarrow\mathbb{C}$ (which it calls "$\sqrt{\cdot}$") with the following two properties:

A: $sqrt$ gives square roots: for all $z$ we have $sqrt(z)^2=z$.

B: $sqrt$ distributes over multiplication: for all $z_0,z_1$ we have $sqrt(z_0)\cdot sqrt(z_1)=sqrt(z_0\cdot z_1)$.

I'll call such a function (if it exists) a good square rooter.

If there were such a function, then the proof would work - so in fact what's being shown is that no such function exists. This can be a stumbling point because of course over $\mathbb{R}_{\ge 0}$ there is such a function, namely the function sending $x$ to its unique nonnegative square root.

OK, so what is it about $\mathbb{C}$ as opposed to $\mathbb{R}_{\ge0}$ that makes the former have no good square rooter?

Well, it turns out that the issue is exactly that elements of $\mathbb{C}$ have multiple square roots in $\mathbb{C}$ in general, whereas each element of $\mathbb{R}_{\ge0}$ has exactly one square root in $\mathbb{R}_{\ge0}$. As soon as we're forced to "make a choice," we lose any hope of having a good square rooter.

To be precise:

Suppose $A$ is a commutative semiring in which every element has at least one square root. Then the following are equivalent:

- Every element in $A$ has exactly one square root.

- There is a good square rooter $sqrt_A:A\rightarrow A$.

Proof: The direction $2\rightarrow 1$ is basically just the argument in the OP! Suppose we have a good square rooter $sqrt_A$, and pick $a,b,c\in A$ with $a^2=b^2=c$. We have $$sqrt_A(c)=sqrt_A(a)\cdot sqrt_A(a)=sqrt_A(b)\cdot sqrt_A(b)$$ by condition B of good-square-rooter-ness, but we also have $$sqrt_A(a)\cdot sqrt_A(a)=a\mbox{ and }sqrt_A(b)\cdot sqrt_A(b)=b$$ by condition A. Put together we get $a=b$ as desired.

In the other direction, suppose $(1)$ holds. Then we can define a function $s: A\rightarrow A$ by $s(a)=$ the unique $b$ with $b^2=a$. This trivially satisfies condition A of good-square-rooter-ness, so we just have to show that $$s(a)\cdot s(b)=s(a\cdot b)$$ for every $a,b\in A$.

And this is nice and easy! By definition of $s$, we have $$[s(a)s(b)]^2=[s(a)^2][s(b)^2]ab=[s(ab)]^2.$$ So $s(a)s(b)$ and $s(ab)$ are elements of $A$ which square to the same thing (namely $ab$), which means .... that they're equal by our assumption that we're in case $(1)$.

"But wait!", you might reasonably say, "what about $\mathbb{R}_{\ge0}$? Positive real numbers do have multiple square roots even though we have a good square rooter in $\mathbb{R}_{\ge0}$. What gives?"

The point is that we get extra square roots for positive reals only when we step outside of $\mathbb{R}_{\ge 0}$. Within $\mathbb{R}_{\ge0}$ itself, every element has exactly one square root. The proposition is very carefully phrased to be about what's going on inside the commutative semiring $X$, not about how $X$ sits inside some yet larger commutative semiring.

So we always have to pay attention to where the solutions to various equations exist!

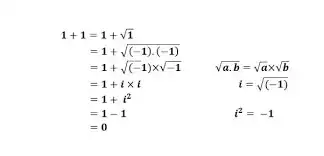

In that sense the first equation isn't even necessarily true, since the square root of 1 COULD be -1 already giving you 2=0, nothing to do with complex numbers.

The equality is only true if 1 is only allowed to be factored as 1*1, which you break in line 2.

– NaiDoeShacks Nov 02 '24 at 09:29