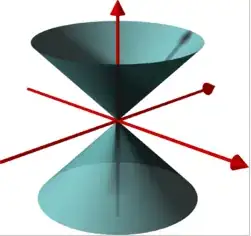

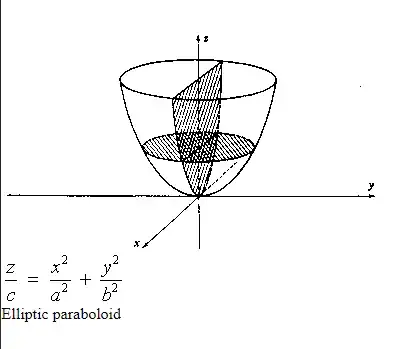

I can't understand why $$\frac{z}{c} = \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} \tag{*}$$ corresponds to an elliptic paraboloid and $$\frac{z^2}{c^2} = \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} \tag{**}$$ to a cone, and not the other way around.

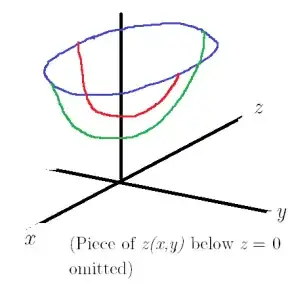

I tried to understand by looking at the traces of $z(x,y)$. For example, I did so for (**):

$\boxed{\text{When } x = k:}$ Then (**) becomes: $\displaystyle \frac{z^2}{c^2} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} =\underbrace{\frac{k^2}{a^2}}_{\text{a constant}} \color{green}{\text{: hyperbolas in the $yz$-plane.}}$

${\boxed{\text{When } y = k:}}$ Then (**) becomes: $\displaystyle \frac{z^2}{c^2} - \frac{x^2}{a^2} = {\underbrace{\frac{k^2}{b^2}}_{\text{a constant}}\color{red}{\text{: hyperbolas in the $xz$-plane.}}}$

$\boxed{\text{When } z = k:}$ Then (**) becomes: $\displaystyle \underbrace{\frac{k^2}{c^2}}_{\text{a constant}} = \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} \color{blue}{\text{: ellipses in the $xy$-plane.}}$

I sketched the following shape based on this information, but it doesn't seem to tell me whether it's an elliptic paraboloid or a cone?

$\Large{\text{Supplementary Question:}}$ Thank you very much to all your answers, all of which helped! Based on them, the key step seems to be to look at the traces of $z(x,y)$ for $k = 0.$ I now understand that this answers my question, but why did my original work with $k \neq 0 $ fail to do so? My textbook doesn't mention the latter straightforward "trick."

$\Large{\text{Question S.1:}}$ @bubba: Thank you very much for your answer to the Supplementary Question. To clarify your answer, did you mean: "but, in either case, these are hyperbolas curves} unless $k=1.$" As I wrote above, for $\text{(*)}$, the traces $x=k \text{ & }y = k$ do yield hyperbolas. But for $\text{(*)}$,

$ \boxed{\text{When } x = k:}$ Then (*) becomes $\displaystyle \frac{z}{c} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} =\underbrace{\frac{k^2}{a^2}}_{\text{a constant}} \text{: PARAbolas in the $yz$-plane.}$

${\boxed{\text{When } y = k:}}$ Then (*) becomes: $\displaystyle \frac{z}{c} - \frac{x^2}{a^2} = {\underbrace{\frac{k^2}{b^2}}_{\text{a constant}}{\text{: PARAbolas in the $xz$-plane.}}}$.

Of course, the fact the traces of (*) are parabolas and NOT hyperbolas still doesn't answer my original question. As you kindly explained and I now understand, it's necessary to consider $k = 0.$