The title of the question motivates the specific mathematical question given in the next section.

Let $A$ be finite set.

For an integer integer $n \ge 0$, a function $s: \{k \mid k \le n \land k \gt 0\} \to A$ is said to be a word (or string) in the alphabet $A$ of length $n$. The collection of all words in $A$ is denoted by $ \mathcal W$. Note that $\emptyset \in \mathcal W$; it is called the null string and is denoted by $[\,]$.

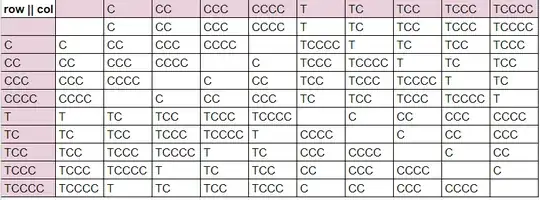

In a natural fashion, any two strings $\mathcal W$ can be concatenated,

$\quad (s,t) \mapsto s \mid t$

so that $(\mathcal W, \; \mid \;)$ is a free monoid.

The elements in $A$ can be regarded as words of length $1$ in $\mathcal W$ and by abuse of notation we write $A \subset \mathcal W$.

Let $\mathcal R \subsetneq \mathcal W$ be a finite set with $A \subset \mathcal R$ and $[\,] \in \mathcal R$.

Let $\Gamma: \mathcal W \to \mathcal R$ be a surjective mapping satisfying

$\tag 1 \Gamma ([\,]) = [\,]$

$\tag 2 \forall a \in A, \quad\Gamma (a) = a$

$\tag 3 \forall s,t \in \mathcal W, \quad \Gamma(s \mid t) = \Gamma\bigr(\Gamma (s) \mid \Gamma (t)\bigr)$

Are there any mathematical specifications (examples) where $\text{(1)-(3)}$ holds?

My Work

I am close to working out the details to representing the symmetric groups with such a framework. I could not find any references, but if it has already been done then that would be an example; any links/comments would be appreciated.

I have a working python program using this representation theory that allowed me to supply this answer to a motivational question.