I'm currently self-studying Lie Algebras and I came across the definition of the Killing Form. As I understand it, the Killing Form gives you an inner product with which you can visualize the roots of a Lie Algebra. Two questions here:

The definition of the Killing Form seems very random. Is there a natural reason why someone would choose this particular inner product with which to visualize the fundamental roots? Is there really no simpler inner product to choose?

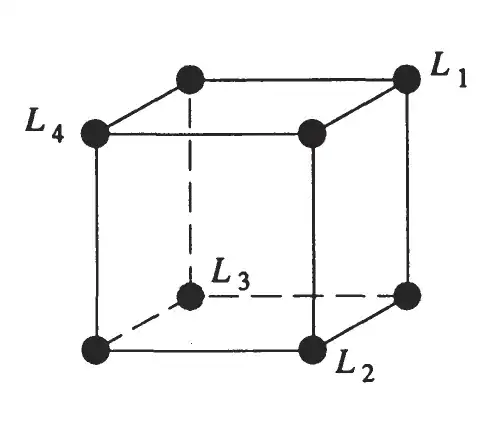

What deeper insight does the root system give you about the Lie Algebra? As an example, I've attached a screenshot of a sample root system below. My issue is that it's so many layers thick with abstraction (each point is an "eigenvalue of the action of Cartan Subalgebra under the adjoint map" -- gosh, even saying that makes my head spin!) that I can't get a grip of what the diagram is saying morally.

To sum up, where I'm at right now is this: "the eigenvalues of the adjoint map form a nice picture if we arrange them according to this seemingly random inner product (the Killing Form)." But why are the eigenvalues of the adjoint map significant, and why is their arrangement in the below diagram significant? I feel like I am missing the big picture. Any suggestions would be appreciated!