For each subset $A$ of $\mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, \dots\}$, we define

$$ f_A(x) := \sum_{n \in A} \frac{x^n}{n!}. $$

1. @mathworker21's proof essentially shows that, for any infinite subset $A$ of $\mathbb{N}_0$,

$$ \limsup_{x\to\infty} \sqrt{x}e^{-x}f_A(x) \geq \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}. $$

So, for any non-constant polynomial $p(x)$, we must have

$$ \limsup_{x\to\infty} |p(x)|e^{-x}f_A(x) = \infty $$

and the OP's condition cannot be satisfied.

2. Based on the above observation, we may formulate another interesting question:

Question. Let $0 \leq \alpha \leq \frac{1}{2}$ and $\ell > 0$. Is there $A \subseteq \mathbb{N}_0$ such that

$$ \lim_{x\to\infty} x^{\alpha} e^{-x}f_A(x) = \ell $$

Case 1. When $\alpha = 0$, we necessarily have $\ell \in (0, 1]$ for an obvious reason. Now we claim that any values of $\ell \in (0, 1]$ can be realized.

Let $m \geq 1$ and $R \subseteq \{0, 1, \dots, m-1\}$. Then

$$ \lim_{x\to\infty} e^{-x} \sum_{q=0}^{\infty}\sum_{r\in R} \frac{x^{qm+r}}{(qm+r)!} = \frac{|R|}{m}. $$

This lemma is an easy consequence of the following explicit computation

\begin{align*}

\sum_{q=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^{qm+r}}{(qm+r)!}

&= \frac{1}{m}\sum_{k=0}^{m-1} e^{-\frac{2\pi i k r}{m}} \exp\left(e^{\frac{2\pi i k}{m}}x\right) \\

&= \frac{e^x}{m} + \mathcal{O}\left(\exp\left(x \cos(\tfrac{2\pi}{m})\right)\right) \qquad\text{as}\quad x \to \infty.

\end{align*}

So, the case of rational $\ell$ is resolved.

When $\ell$ is irrational, define $A$ by as follows: Set

$$ A_1 = \begin{cases}

\{0\}, & \text{if $\ell \in (0,\frac{1}{2}]$}; \\

\{0,1\}, & \text{if $\ell \in (\frac{1}{2}, 1]$}.

\end{cases} $$

Next, suppose that $A_k$ is defined and contains $\lceil 2^k \ell \rceil$ elements. Consider the set $A_k \cup (2^k + A_k)$. This set contains $2\lceil 2^k \ell \rceil$ elements. Then by removing its last element if necessary, reduce the number of its elements to $\lceil 2^{k+1}\ell \rceil$. Denote the resulting set by $A_{k+1}$. Finally, set $A = \cup_{k=1}^{\infty} (2^k + A_k)$. It can be shown that this set achieves the desired property.

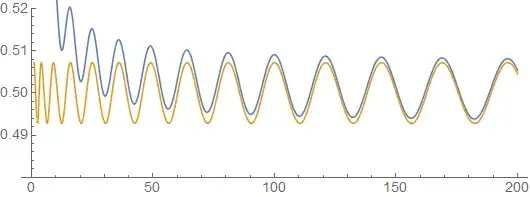

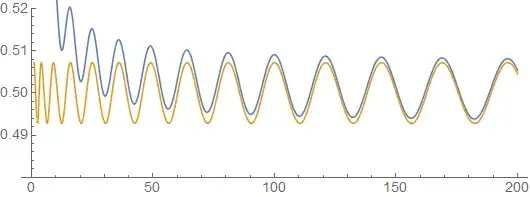

Case 2. When $\alpha = \frac{1}{2}$, I suspect that no such $\ell$ exists. I have a couple of heuristic arguments for this guess, mainly based on the case $A = \{n^2 : n \in \mathbb{N}_0\}$. A heuristic computation suggests that

$$ \sqrt{x}e^{-x} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^{n^2}}{(n^2)!} \sim \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-\frac{(2k-r)^2}{2}}, \qquad r = \frac{x-\lfloor\sqrt{x}\rfloor^2}{\sqrt{x}} $$

$$ \textbf{Figure.} \ \text{ A comparison of the left-hand side (blue) and the right-hand side (orange).}$$

which oscillates as $x\to\infty$. The main mechanism of this oscillatory behavior is that, if $x$ is large, then each term $\frac{x^n}{n!}$ with $n = x + \mathcal{O}(x^{1/2})$ will contribute to $\sqrt{x}e^{-x}f_A(x) $. I am currently trying to formalize this idea to prove my conjecture.

Case 3. When $0 < \alpha < \frac{1}{2}$, I propose the following conjecture:

- Conjecture. Let $\beta = \frac{1}{1-\alpha}$ and $c > 0$, and define $A$ by

$$ A = \{ \lfloor (cn)^{\beta} \rfloor : n \geq 0 \}. $$

Then

$$ \lim_{x \to \infty} x^{\alpha} e^{-x} f_A(x) = \frac{1}{\beta c}. $$

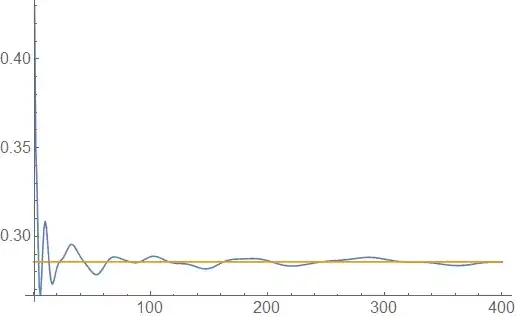

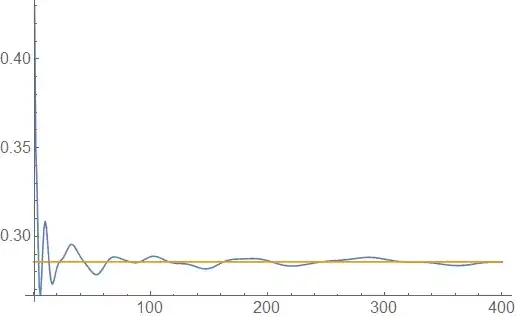

For instance, the following example illustrates the case of $\alpha = \frac{1}{7}$ and $c = 3$:

$$ \textbf{Figure.} \ \text{ $x^{\alpha}e^{-x}f_A(x)$ (blue) and its limit $\frac{1}{\beta c}$ (orange) when $\alpha = \frac{1}{7}$ and $c = 3$}$$

For the remaining portion of this part, we sketch the proof of this conjecture when $0 < \alpha < \frac{1}{6}$. The main idea is that the sum can be truncated:

- Lemma. Fix a function $\lambda = \lambda(x) \geq 0$ such that $\lambda \to \infty$ and $\frac{\lambda}{\sqrt{x}} \to 0$ as $x \to \infty$. Then there exists a constant $C > 0$, depending only on $\lambda$, such that

$$ e^{-x} \sum_{|n - x| > \lambda\sqrt{x}} \frac{x^n}{n!} \leq \frac{C}{\lambda}. $$

Now we further assume that $\frac{\lambda}{x^{1/6}} \to 0$ as $x \to \infty$. Then using the above lemma, we can show:

$$ e^{-x}f_A(x) = \frac{1 + \mathcal{O}(\lambda^3/\sqrt{x})}{\sqrt{2\pi x}} \sum_{\substack{|m - x| \leq \lambda\sqrt{x} \\ m \in A}} e^{-\frac{(m-x)^2}{2x}} + \mathcal{O}\left(\frac{1}{\lambda}\right). $$

For each $m \in A$, let $n_m$ be defined by $m = \lfloor (c n_m)^{\beta} \rfloor$, and write $t_m = n_m - c^{-1}x^{1/\beta}$. Then we can show that, uniformly in $x$ and $m \in A \cap [x-\lambda\sqrt{x}, x+\lambda\sqrt{x}]$,

$$

\frac{(m-x)^2}{2x}

= \frac{1}{2} \biggl( \frac{\beta c t_m}{x^{\frac{1}{2}-\alpha}} \biggr)^2 + o(1).

$$

So, if in addition $\lambda$ is chosen that $x^{\alpha}/\lambda \to 0$ (which is possible by letting $\lambda(x) = x^{\gamma}$ for some $\gamma \in (\alpha, \frac{1}{6})$), then

$$ x^{\alpha} e^{-x}f_A(x) = \frac{1 + o(1)}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \sum_{\substack{|m - x| \leq \lambda\sqrt{x} \\ m \in A}} \exp\biggl[ - \frac{1}{2} \biggl( \frac{\beta c t_m}{x^{\frac{1}{2}-\alpha}} \biggr)^2 \biggr] \frac{1}{x^{\frac{1}{2}-\alpha}} + o(1), $$

which converges to

$$ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-\frac{(\beta c u)^2}{2}} \, \mathrm{d}u = \frac{1}{\beta c} $$

as $x \to \infty$.

3. For different lines of questions regarding the asymptotic behavior of $f_A(x)$, see: