The way I was introduced to the identities in high school precal. Let's start with subtraction of angles.

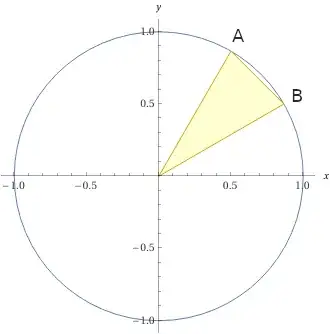

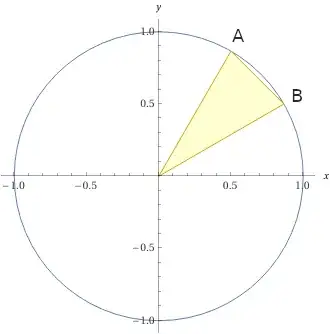

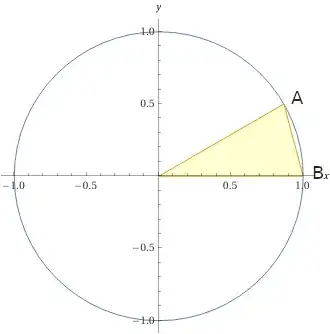

Let $A = (\cos\alpha, \sin\alpha)$ and $B = (\cos\beta, \sin\beta)$ be two points on the unit circle.

Then the distance between them is

$$d = \sqrt{(\cos\alpha - \cos\beta)^2 + (\sin\alpha - \sin\beta)^2}$$

$$= \sqrt{\cos^2\alpha - 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta + \cos^2\beta + \sin^2\alpha - 2\sin\alpha\sin\beta + \sin^2\beta}$$

$$= \sqrt{(\cos^2\alpha + \sin^2\alpha) + (\cos^2\beta + \sin^2\beta) - 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta - 2\sin\alpha\sin\beta}$$

$$= \sqrt{2 - 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta - 2\sin\alpha\sin\beta}$$

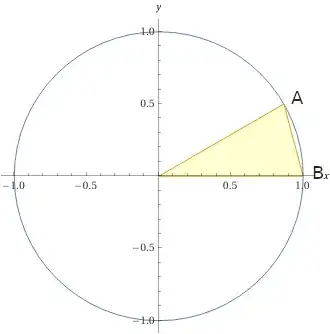

Now, let's rotate the coordinate system so that $B = (1, 0)$ and $A = (\cos(\alpha - \beta), \sin(\alpha - \beta))$.

Then the distance between the points is:

$$d = \sqrt{(\cos(\alpha - \beta) - 1)^2 + \sin^2(\alpha-\beta)}$$

$$= \sqrt{\cos^2(\alpha - \beta) - 2\cos(\alpha - \beta) + 1 + \sin^2(\alpha-\beta)}$$

$$= \sqrt{1 + (\cos^2(\alpha - \beta) + \sin^2(\alpha-\beta)) - 2\cos(\alpha - \beta)}$$

$$= \sqrt{2 - 2\cos(\alpha - \beta)}$$

But since the distance between $A$ and $B$ must be the same either way, we have:

$$= \sqrt{2 - 2\cos(\alpha - \beta)} = \sqrt{2 - 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta - 2\sin\alpha\sin\beta}$$

$$= 2 - 2\cos(\alpha - \beta) = 2 - 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta - 2\sin\alpha\sin\beta$$

$$-2\cos(\alpha - \beta) = -2\cos\alpha\cos\beta - 2\sin\alpha\sin\beta$$

$$\boxed{\cos(\alpha - \beta) = \cos\alpha\cos\beta + \sin\alpha\sin\beta}$$

Now, let's do $\cos(\alpha + \beta)$. That's equivalent to $\cos(\alpha - (-\beta))$, so by the above formula,

$$\cos(\alpha + \beta) = \cos\alpha\cos(-\beta) + \sin\alpha\sin(-\beta)$$

But $\cos$ is even (i.e., $\cos(-\beta) = \cos(\beta)$) and $\sin$ is odd (i.e., $\sin(-\beta) = -\sin(\beta)$), so:

$$\boxed{\cos(\alpha + \beta) = \cos\alpha\cos\beta - \sin\alpha\sin\beta}$$

Now we need similar formulas for $\sin$. Start by using the Pythagorean identity

$$\sin^2(\alpha - \beta) + \cos^2(\alpha - \beta) = 1$$

$$\sin^2(\alpha - \beta) + (\cos\alpha\cos\beta + \sin\alpha\sin\beta)^2 = 1$$

$$\sin^2(\alpha - \beta) + \cos^2\alpha\cos^2\beta + 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta\sin\alpha\sin\beta + \sin^2\alpha\sin^2\beta = 1$$

$$\sin^2(\alpha - \beta) + (1 - \sin^2\alpha)(1 - \sin^2\beta) + 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta\sin\alpha\sin\beta + \sin^2\alpha\sin^2\beta = 1$$

$$\sin^2(\alpha - \beta) + 1 - \sin^2\alpha - \sin^2\beta + \sin^2\alpha\sin^2\beta + 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta\sin\alpha\sin\beta + \sin^2\alpha\sin^2\beta = 1$$

$$\sin^2(\alpha - \beta) = \sin^2\alpha + \sin^2\beta - 2\sin^2\alpha\sin^2\beta - 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta\sin\alpha\sin\beta$$

$$\sin^2(\alpha - \beta) = (\sin^2\alpha)(1 - \sin^2\beta) + (\sin^2\beta)(1 - \sin^2\alpha) - 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta\sin\alpha\sin\beta$$

$$\sin^2(\alpha - \beta) = \sin^2\alpha\cos^2\beta + \cos^2\alpha\sin^2\beta - 2\cos\alpha\cos\beta\sin\alpha\sin\beta$$

$$\sin^2(\alpha - \beta) = (\sin\alpha\cos\beta - \cos\alpha\sin\beta)^2$$

$$\sin(\alpha - \beta) = \pm (\sin\alpha\cos\beta - \cos\alpha\sin\beta)$$

Which leaves the question: Plus or minus? If we plug in $\beta = 0$, we get:

$$\sin(\alpha) = \pm (\sin\alpha\cos(0) - \cos\alpha\sin(0)) = \pm \sin\alpha$$

Similarly, if $\alpha = 90°$, then:

$$\sin(90° - \beta) = \pm (\sin(90°)\cos\beta - \cos(90°)\sin\beta)$$

$$\cos(\beta) = \pm \cos\beta$$

Clearly, plus is the correct choice.

$$\boxed{\sin(\alpha - \beta) = \sin\alpha\cos\beta - \cos\alpha\sin\beta}$$

And, using the same odd/even function approach as before,

$$\sin(\alpha + \beta) = \sin\alpha\cos(-\beta) - \cos\alpha\sin(-\beta)$$

$$\boxed{\sin(\alpha + \beta) = \sin\alpha\cos\beta + \cos\alpha\sin\beta}$$

Note that I have not made an acute angle assumption anywhere.