There are various ways of defining the sine function depending on what you want to use it on. So if all you need is acute angles, then the right angled triangle works just fine. But what if you see a physics equation that plugs time into a sine function (such as those seen in harmonic motion) and so this is not always going to be an acute angle, so we need a broader definition. This is where the idea of the unit circle is often employed.

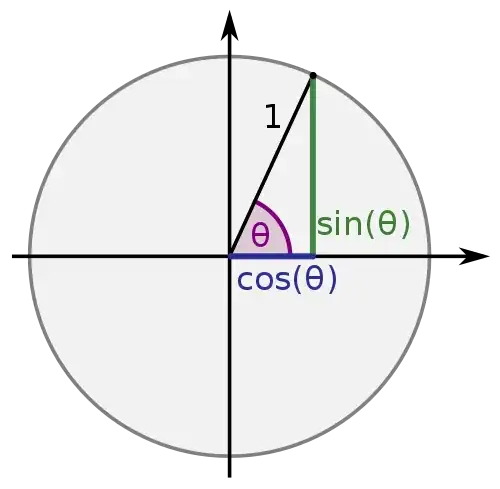

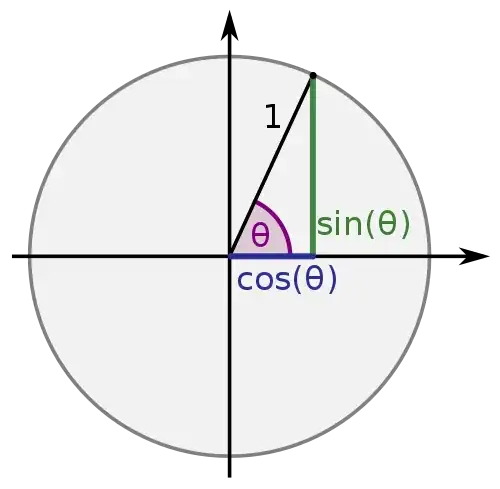

This allows you to define, for any real angle $\theta$, what the value of $\sin \theta$ and $\cos \theta$ (and from that all the other trig ratios you might like) is. This works for angles other than acute angles because you can just keep going round and round the circle and the coordinates of the point are always $(\cos \theta, \sin \theta)$.

This can be seen as taking an approach with agrees with what we have already in the acute angles case and then adding to it so that it works in new contexts too.

So someone who thought trigonometry was only about right angled triangles might make the argument here that this is no longer trigonometry - we've just made something up and there's no evidence that this is what it is actually like.

But this is kind of the point, we have to make stuff up in maths. As long as it's consitent with what we had before i.e. it doesn't break stuff, then it's fine. And if it turns out to be useful (as this very much is) then it's far better than fine.

A very similar idea applies when you try to extend the sine function defintion to apply to even more than the real numbers. It can be shown using calculus that the sine function is equal to an infinite polynomial (this is how a lot of calculators actually work out arbitrary trig values). Now there's no reason that this infinite polynomial should only be allowed to have real numbers plugged into it, you can start plugging imaginary or complex numbers into it and the polynomial just deals with it and gives you an answer (you can even find the sine of a matrix using the series defintion). But this has no representation looking at our poor old triagnles we had in the beginning, what has happened?

We've just used the idea of abstraction away from the original circumstances it was envisioned within and generalised it so it becomes more useful and can answer more problems. It still works fine for acute angles, it just works for a whole lot more beyond that.

So to summarise, we can define stuff however we like and as long it doesn't mess with what we've already got then we can use it along-side everything else we've already got. And often this extension turns out to be useful so that we can solve problems we didn't have techniques to solve before. And if it's useful and works then often it becomes the accepted definition.