From a given data :

$$(x_1\:,\:y_1),(x_2\:,\:y_2),...,(x_k\:,\:y_k),...,(x_n\:,\:y_n)$$

A simplistic method (but not always efficient) consists in :

- Computing the derivatives approximates :

$$y'_k=\frac{y_{k+1}-y_{k-1}}{x_{k+1}-x_{k-1}}\quad\text{from}\quad k=2\quad\text{to}\quad k=n-1$$

$$y''_k=\frac{y'_{k+1}-y'_{k-1}}{x_{k+1}-x_{k-1}}\quad\text{from}\quad k=3\quad\text{to}\quad k=n-2$$

- Putting them into the differential equation $y''+x^2y'+x=0$ in order to compute the errors :

$$\epsilon_k=y''_k+x^2_ky'_k+x_k$$

- Then an usual statistical study of the errors (depending on the criterial of fitting).

This method is not recommended in case of non negligible scatter and/or bad distribution of the points because the resulting scatter on the approximate differentials might become very high.

For this kind of approach an integral equation is generally better because the numerical integration tends to smooth the scatter while the numerical differentiation tends to reinforce the scatter.

The differential equation can be transformed into an integral equation thanks to analytical integrations :

$$y''+x^2y'+x=0$$

$$y'+x^2y-2\int xy\:dx+\frac12 x^2=c_1$$

$$y+\int x^2y\:dx-2\int\int xy\:(dx)^2+\frac16 x^3=c_1x+c_2$$

For numerical calculus

$$y_k+T_k-2\,V_k+\frac16 x_k^3\simeq c_1x_k+c_2$$

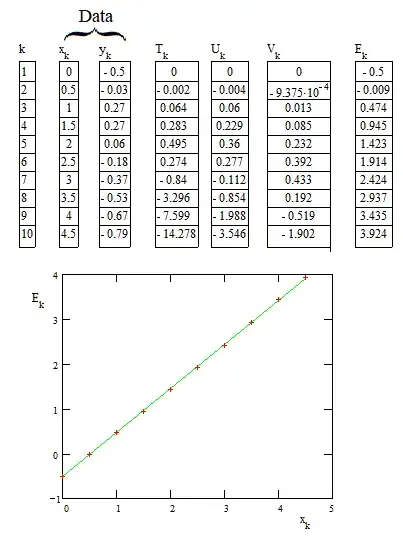

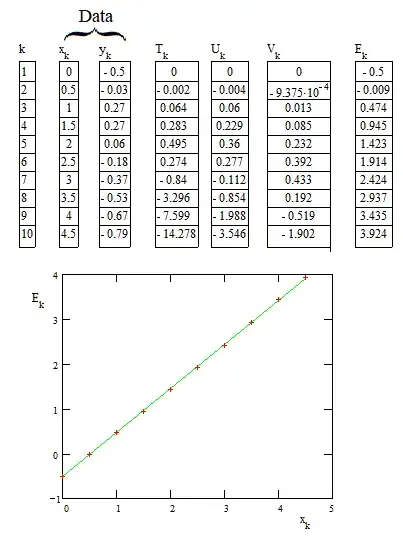

$T_1=0\quad;\quad T_k=T_{k-1}+\frac12 (x_k^2y_k+x_{k-1}^2y_{k-1})(x_k-x_{k-1})\quad$ from $k=2$ to $k=n$.

$U_1=0\quad;\quad U_k=U_{k-1}+\frac12 (x_ky_k+x_{k-1}y_{k-1})(x_k-x_{k-1})\quad$ from $k=2$ to $k=n$.

$V_1=0\quad;\quad V_k=V_{k-1}+\frac12 (U_k+U_{k-1})(x_k-x_{k-1})\quad$ from $k=2$ to $k=n$.

We compute $\quad E_k=\big(y_k+T_k-2\,V_k+\frac16 x_k^3\big)\quad$ and check if the relationship with $x_k$ is linear. The statistical analysis of the errors according to some specified criteria of fitting allows to say if the data fits to a solution (not explicit) of the differential equation.

For more information about the method of fitting with integral equation : https://fr.scribd.com/doc/14674814/Regressions-et-equations-integrales

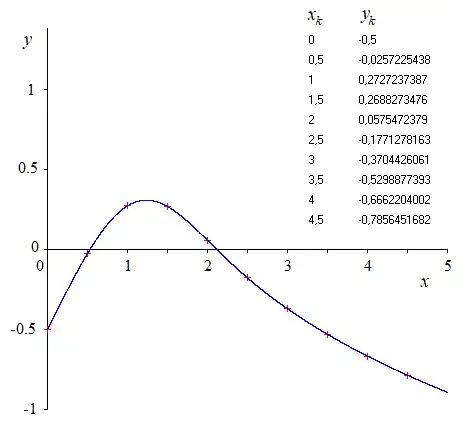

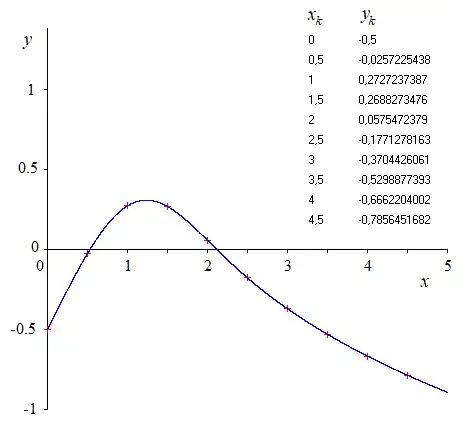

In addition, NUMERICAL EXAMPLE :

We observe that the $E_k(x_k)$ is quite linear as expected if the data approximately fits a solution of the differential equation. The linear regression gives

$$E_k\simeq c_1\:x_k+c_2\quad\text{with } c_1=0.994\:;\: c_2=-0.517$$

After computing $c_1$ and $c_2$ it is possible to evaluate the initial conditions (at $x=x_1$) :

$$y(x_1)=c_1x_1+c_2-\frac16 (x_1)^3\simeq y_1$$

$$y'(x_1)=c_1-(x_1)^2 y(x_1)-\frac12 (x_1)^2$$

For the above example the calculus was simplified because $x_1=0$ .

In fact, if the data was not approximate but exact and if the numerical integrations for $T_k,U_k,V_k$ were also exact, we should have found $c_1=1$ and $c_2=-0.5$

Of course all above doesn't gives the solution of the differential equation. Numerical methods and sofwares exist for solving the ODEs, given some conditions.

FOR INFORMATION :

The data was coming from the numerical solving of $y''+x^2y'+x=0$ with conditions $y'(0)=1$ and $y(0)=-0.5$ for example. Then rounded $y_k$ were taken as data to be used for the above numerical example.