You're asking for intuition around the following fact:

"If $A$ is the covariance matrix, and you want to maximize (or minimize) $f(x)=x^TAx$ under the constraint that $\|x\|^2=1$, then any solution $x_0$ will be such that $x_0$ and $Ax_0$ are collinear."

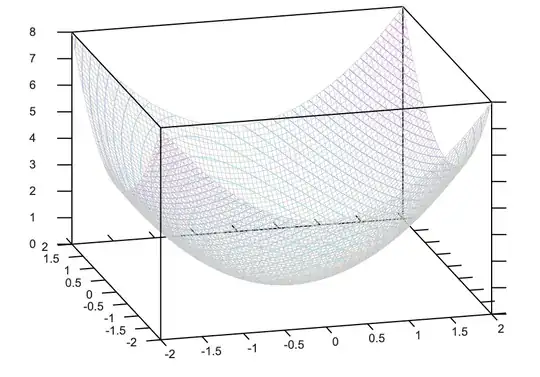

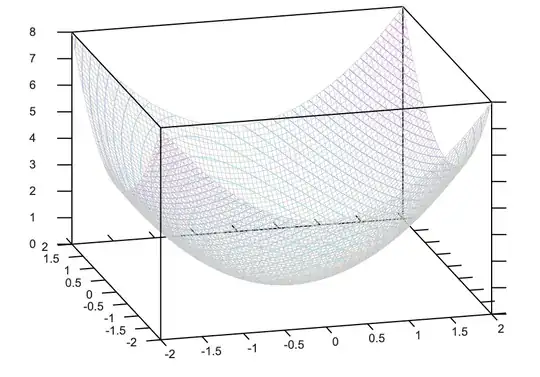

To see this geometrically, consider the level sets of $x^TAx$. Those are the set of point where $x^TAx$ assumes the same value. You can verify that those level sets are ellipsoids whose axes are aligned along $A$'s eigenvectors.

Now let's go back to the maximization of $x^TAx$ under the constraint that $\|x\|^2=1$. To build an intuition, assume we take a gradient descent approach. The way it works: You start somewhere, then start following the gradient of the function $x^TAx$, while continuing to satisfy the constraint $\|x\|^2=1$, and repeat until you can no longer move.

Now, note the following

The gradient of $x^TAx$ is equal to $Ax$.

If you are at a point $x$ satisfying the constraint, and you want to move away while still satisfying that constraint, then you must move in a direction that's orthogonal to the direction of the gradient of that constraint. In the case of the $\|x\|^2=1$ constraint, that means you must move in a direction orthogonal to $x$.

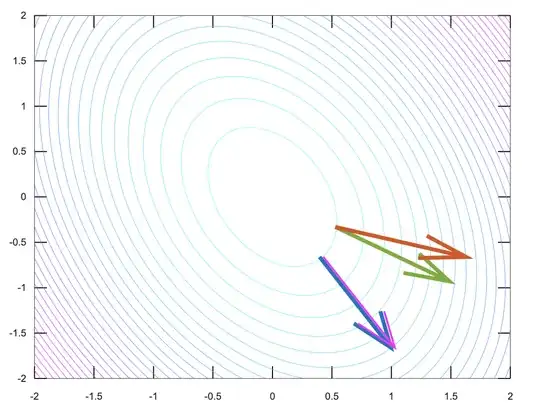

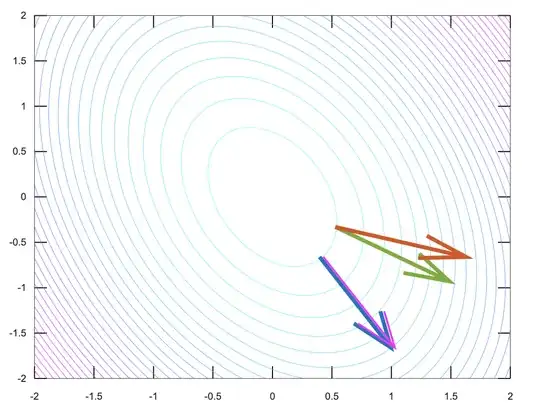

In the picture below, we represent the level sets of the function $x^TAx$ to optimize. Suppose you are at the point where the red and green arrows meet. The red arrow is $Ax$, and the green arrow is $x$. Then you can easily see that by moving in a direction orthogonal to the green arrow, you can reach another level set, one with a higher value of $x^TAx$ (as indicated by the red arrow). So as long as you're in such a configuration where $Ax$ and $x$ are not collinear, you can always move to another point where the constraint is satisfied and you increase the function $x^TAx$.

Contrast this with the situation where both $Ax$ (pink arrow) and $x$ (blue arrow) are collinear. Now, if you move in a direction orthogonal to $x$ (to satisfy the constraint), you'll also move in a direction that's orthogonal to $Ax$, achieving no variation of the function to optimize. In that case, you're already at an extremum.

This proves that extrema of a function under a constraint are achieved when both gradients of the function and constraint are collinear.

Finally, note that none of this depends on the particular form for the function as $f(x)=x^TAx$ or the constraint as $\|x\|^2=1$. The reasoning I presented is a geometric proof of Lagrange multipliers for general functions and constraints.