You need to be specific about what it means that factorial grows faster than exponential. And if you think about it, it means that $$ \lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} \frac{a^n}{n!} = 0$$

This is basically what you need to prove, so you cannot use that in the proof. Comparing this sequence with a geometric series is the easiest way I know.

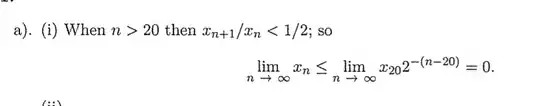

As for you last question, you need a bit stronger condition. If you have $x_n>0$ and can prove that there exist $q<1$ and $N$ such that for $n>N$ you have

$$ \frac{x_{n+1}}{x_n} < q$$

then it is enough to prove that $x_n\rightarrow 0$. This is because you have then

$$\forall n>N: x_{n} < x_{N} \cdot q^{n-N} \rightarrow 0$$

which means $$ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} x_n =0$$

Knowing just that $$ \frac{x_{n+1}}{x_n} < 1$$ is not enough, for example for $x_n = \frac{n}{2n-1}$ you have

$$ \frac{x_{n+1}}{x_n} = \frac{(n+1)(2n-1)}{(2n+1)n} = \frac{2n^2+n-1}{2n^2+n} < 1$$ but $$ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} x_n = \frac12$$