When answering this question about finding the open unit ball $\mathscr{B} := \{ x \in \mathbb{R}^2: \| x \| < 1\}$ of the "composite" norm $$ \| \cdot \|: \mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}, \ (x,y) \mapsto a \| (x,y) \|_1 + \frac{b}{2} \| (x,y) \|_{\infty}. $$ I thought of the following question. In the above question one has $\Omega := \mathbb{R}^2$, $a := \frac{1}{3}$ and $b := \frac{4}{3}$ but those aren't important for my question. All that matters is $a,b > 0$, as verified in this question.

It turns out that $\mathscr{B}$ is a octagon (as intersection of two rotated squares, as they are the geometric interpretations of $\| \cdot \|_1$ and $\| \cdot \|_{\infty}$ (is that really true?), which can be seen in the diagram appended to my answer to the first mentioned question).

My question is if (and how) one can find out which shape (polygon?) $\mathscr{B}$ corresponds for a composite norm of the form $$ \| \cdot \| := \sum_{k = 1}^{\infty} \alpha_k \| \cdot \|_{x_k}, \qquad \text{where } \alpha_k \ge 0, x_k \in [1, \infty]. $$ As @CalvinKohr points out in the comments, we can normalize this representation: $\sum_{k} \alpha_k = 1$ such that the sum is well defined i.e. converges.

This question seems to be related but I don't know how the Minkowski functional would relate to this problem even though it was briefly covered in my Functional Analysis course. It remarks that a polygon with a odd number of vertices can not occur because of the symmetry of the norm. As you can see in the last example below, other shapes than octagons are possible. Can $\mathscr{B}$ be another polygon with an even number of vertices?

Maybe this is related to the concept of polyhedral norms?

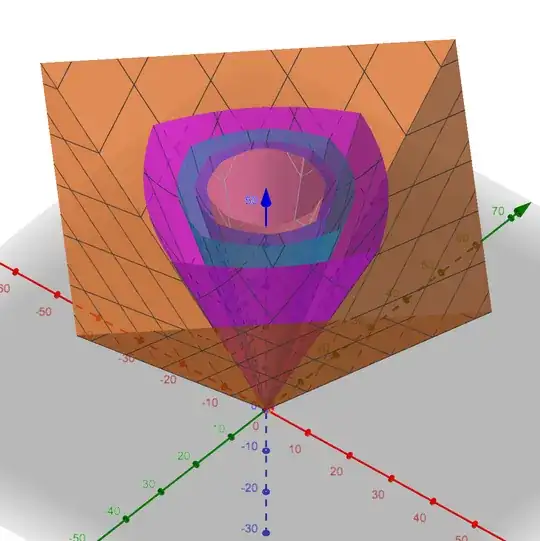

One special case Cosider the norm $\mathfrak{p}_n(x,y) := \sum_{k = 1}^{n} \| (x,y) \|_{k}$. If we graph it and intersect it with a plane $z = \ell$ for $\ell > 0$ we obtain the the shape of $\mathscr{B}$. I graphed $\mathfrak{p}_n$ for $n \in \{1, \ldots, 5\}$ and one observes that shapes of $\mathscr{B}$ are 4-gons that "get more convex" and converge to some circle.

This suggests it might by only interesting to at norms whose $\mathscr{B}$ is a polygon i.e. $\mathscr{B}$s with straight lines. Are those just produced by $\| \cdot \|_1$ and $\| \cdot \|_{\infty}$?.