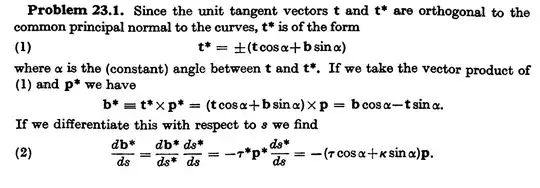

A year ago I asked [this] (Proving a few properties of Bertrand curves) same question (without the "why can't a curve be a Bertrand mate of itself" part) - see that post if you want to know the essential definitions - and gave a partial answer to the first question (I showed it was constant, but hand-waved away a sign in the last step). At the time I was a lot less mature so I made a few steps that currently seem unjustified, and unfortunately even now I seem to be unable to correct them, which is why I'm asking this question. Before I did that, however, I tried to find other solutions besides my own partial one and found this on Kreyszig's differential geometry book, which is essentially what I wrote on the other post, but more direct:

where the following notation is used: $t^{*}$ is the tangent vector to $x^{*}$, which is a Bertrand mate to $x$, $p$ is the normal vector to $x$. The * just mean we're talking about vectors tangent/normal/binormal to $x^{*}$ instead of $x$. That being said, my questions are:

Isn't the correct expression given by $t^{*} = t \cos(\alpha) \pm b \sin(\alpha) $? After all, $t^{*} = \langle t^{*}, t \rangle t + \langle t^{*}, b \rangle b $, and $\langle t^{*}, b \rangle ^2 = \sin^2(\alpha)$, since $\langle t^{*}, t^{*} \rangle = 1$, where $\langle t, t^{*} \rangle = \cos(\alpha)$ by definition. Also, in that case what determines the $\pm$ sign, and how?

- What, if any, are the problems in assuming $\alpha$ is a Bertrand mate of itself, that is, $a = 0$? Is it just uninteresting or is there some other unwanted complication?

Also, my proof was right but I forgot to take care of a lot of signs. A friend showed me his resolution and I know where I went wrong there.

(also, I have moved on to a lot more stuff since that question, I'm not still solely studying curves hahaha, this question was really just for peace of mind)

– Matheus Andrade May 04 '19 at 21:04