I'll prove a partial result that hopefully someone can complete to showing that $f(x) \equiv 0$ is the unique continuous and $L^2(\mathbb{R}_{>0})$ solution. Beyond that, perhaps one can use that continuous functions are dense in $L^2$ to get the requested result. The main tool I want to contribute is the following lemma:

$\mathbf{Lemma}:$ Consider $f \in C(\mathbb{R}_{>0}) \cap L^2(\mathbb{R}_{>0})$. Then for any choice of $0<x_0<y_0 \leq \infty$, we have

$$f(x_0) = \lim_{n \to \infty} ne^{nx_0}\int_{x_0}^{y_0}\frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}}dx $$

$\mathbf{Proof}:$ Fix $\epsilon>0$ and, by continuity, choose $\delta>0$ such that $|x-x_0| < \delta \implies|f(x)-f(x_0)| < \epsilon$. Note that

$$\lim_{n \to \infty} ne^{nx_0} \int_{x_0}^{x_0+\delta} \frac{1}{1+e^{nx}}dx = 1$$

and

\begin{align}

\lim_{n \to \infty} \left | n e^{nx_0} \int_{x_0+\delta}^{y_0}\frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}} dx \right |

& \leq \lim_{n \to \infty} n e^{nx_0} \int_{x_0+\delta}^{y_0} e^{-nx} |f(x)| dx \\

& \leq \lim_{n \to \infty} n e^{nx_0} e^{-(n-1)(x_0+\delta)} \int_{x_0+\delta}^{y_0} e^{-x} |f(x)| dx \\

& \leq \lim_{n \to \infty} n e^{x_0+\delta} e^{-n\delta} \|e^{-x}f(x)\|_1 \\

& \leq \lim_{n \to \infty} n e^{x_0+\delta} e^{-n\delta} \|e^{-x}\|_2 \cdot \|f\|_2 \\

& = 0

\end{align}

by Holder's inequality (neither of these depended on the choice of $\delta$-- they're just straightforward computation/comparison). Given these results, we see that

\begin{align}

\lim_{n \to \infty} \left |ne^{nx_0} \int_{x_0}^{y_0} \frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}}dx - f(x_0) \right |

& = \lim_{n \to \infty} \left |ne^{nx_0} \int_{x_0}^{x_0+\delta} \frac{f(x)-f(x_0)}{1+e^{nx}}dx \right | \\

& \leq \lim_{n \to \infty} ne^{nx_0} \int_{x_0}^{x_0+\delta} \frac{|f(x)-f(x_0)|}{1+e^{nx}}dx \\

& \leq \epsilon

\end{align}

Since $\epsilon>0$ was arbitrary, this proves the lemma.

$$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

This lemma gives us some insight into the behavior of functions satisfying your condition. In particular, if $f$ satisfies these hypotheses and the condition under consideration, we must have for any $x_0 > 0$ that

$$0 = \lim_{n \to \infty} ne^{nx_0} \int_{0}^\infty \frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}}dx = f(x_0) + \lim_{n \to \infty} ne^{nx_0} \int_{0}^{x_0} \frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}}dx$$

Or

$$f(x_0) = -\lim_{n \to \infty} ne^{nx_0} \int_0^{x_0} \frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}}dx $$

From this result, we have $\forall$ $0<x_0<y_0<\infty$ that

$$\lim_{n \to \infty} ne^{nx_0} \int_0^{y_0} \frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}}dx = \lim_{n \to \infty} e^{-n(y_0-x_0)} \left [ ne^{ny_0} \int_0^{y_0} \frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}}dx \right ] = 0 \cdot (-f(y_0)) = 0 $$

and similarly $\forall$ $0 < w_0 < x_0$ with $f(w_0) \neq 0$, the expression

$$ne^{nx_0} \int_0^{w_0} \frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}}dx = e^{n(x_0-w_0)} \left [ ne^{nw_0} \int_0^{w_0} \frac{f(x)}{1+e^{nx}}dx \right ] $$

diverges to $-\text{sgn}(f(w_0)) \cdot \infty$ as $n \to \infty$, since the term in brackets approaches $-f(w_0)$.

Now, suppose $f$ is not identically $0$, so the set

$$\{t >0 | f \equiv 0 \text{ on } (0,t) \}$$

is bounded above; define $T_1$ as the supremum of this set if it is nonempty and $0$ if it is empty. Suppose $\exists T_2>T_1$ such that

$$ T_1 < t < T_2 \implies f(t) \neq 0$$

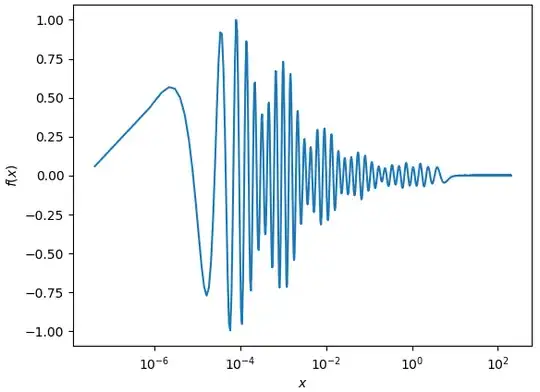

Then $f$ is nonzero on $(T_1,T_2)$ by definition, so by the Intermediate Value Theorem $f$ cannot change sign in this interval. Thus either $f(x) \geq 0$ or $-f(x) \geq 0$ on $(0,T_2)$-- WLOG assume the former, so that for any $x_0 \in (T_1,T_2)$ the first identity after the lemma gives that $f(x_0) \leq 0$, showing $f(x_0)=0$, a contradiction. We therefore conclude that no such $T_2$ exists, i.e. $\forall t>T_1$ $\exists s \in (T_1,t)$ such that $f(s)=0$. That is to say, on any interval containing $0$ on which $f$ is not identically zero, $f$ must have infinitely many roots greater than $T_1$. In particular, the suggestion $f(x)=e^{-x^{1/4}} \sin(x^{1/4})$ cannot be a solution.

Note that if one can use the above results to show that $T_1 = 0$, it would establish that no continuous solution with compact support on $\mathbb{R}_{>0}$ exists (relevant because such functions are dense in $L^2(\mathbb{R}_{>0})$).