Here's something important to keep in the back of your mind when studying graphs: the definition of a graph. There are actually a few deviations in how one can define a graph, but this one will suffice for our purposes:

A (simple) graph $G$ is an ordered pair of set $(V, E)$ (the sets of vertices and edges respectively), where $E$ consists of subsets of $V$ of cardinality $2$.

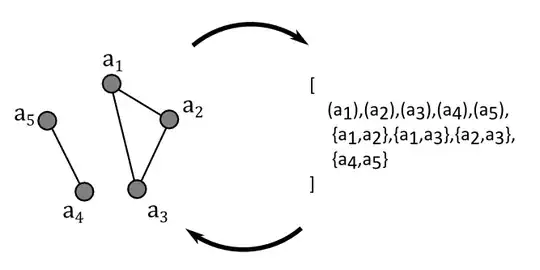

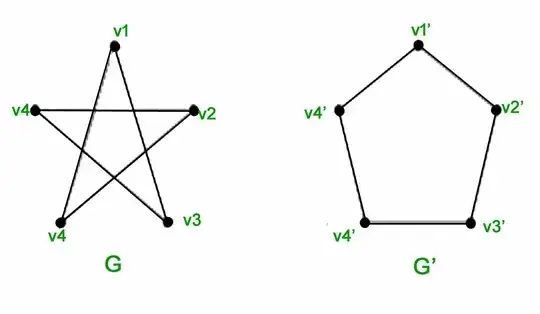

When the graph is finite (meaning $V$, and hence $E$, is a finite set), we can visually represent a graph by a diagram, assigning each point from $V$ to a distinct point in $\Bbb{R}^2$ (or occasionally, $\Bbb{R}^3$). If $\{u, v\} \in E$, then we draw a path from the point representing $u$ to the point representing $v$, going through no other point representing a point in $V$.

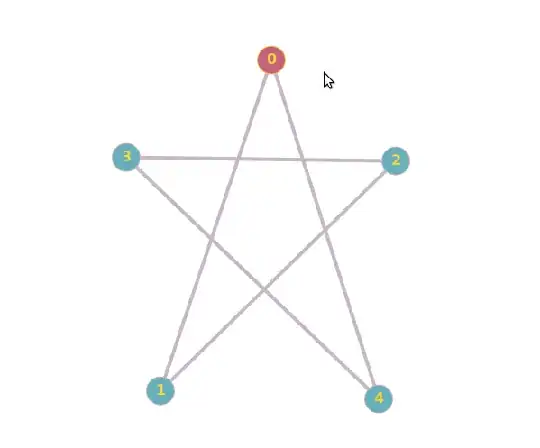

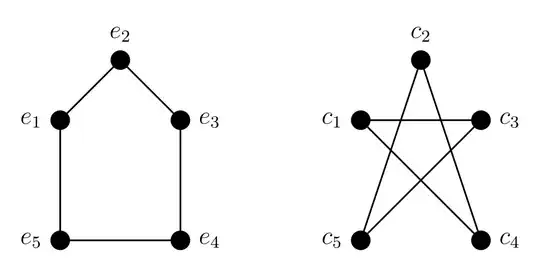

These diagrams are what we often tell people are "graphs", but they are really just a way to represent graphs. The first diagram represents the graph:

$$G_1 = (\{e_1, e_2, e_3, e_4, e_5\},\{\{e_1, e_2\},\{e_2, e_3\}, \{e_3, e_4\}, \{e_4, e_5\}, \{e_5, e_1\}\}).$$

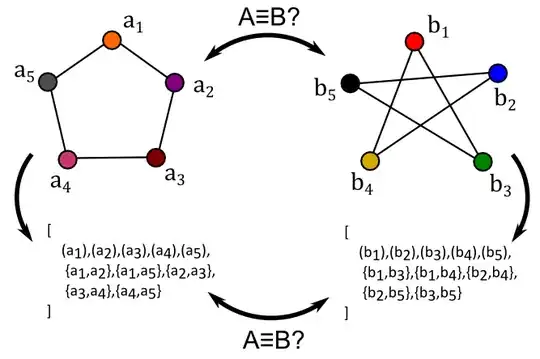

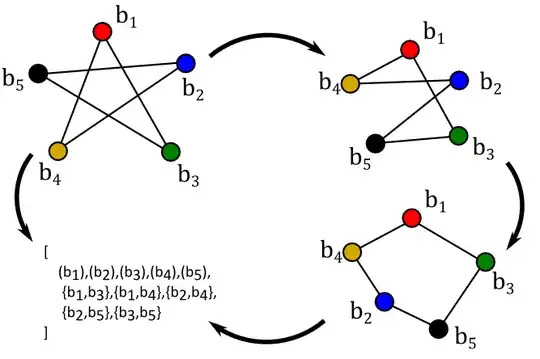

The second diagram represents the graph:

$$G_2 = (\{c_1, c_4, c_2, c_5, c_3\},\{\{c_1, c_4\},\{c_4, c_2\}, \{c_2, c_5\}, \{c_5, c_3\}, \{c_3, c_1\}\}).$$

(Note the leading way in which I've decided to order the elements of my sets in defining $G_2$!)

Note that, if we took the picture of $G_1$ and, say, rotated it (keeping all the labels), then that picture would represent the same graph $G_1$. Not something isomorphic to $G_1$, I mean it would have exactly the same vertex and edge sets, i.e. the graph it represents would literally be $G_1$, even though it's a new picture. You could even start moving the vertices around independently of each other (again, keeping the same labels), and the diagram will continue to represent $G_1$.

In this way, we see that there is an enormous variety of diagrams to represent exactly the same graph.

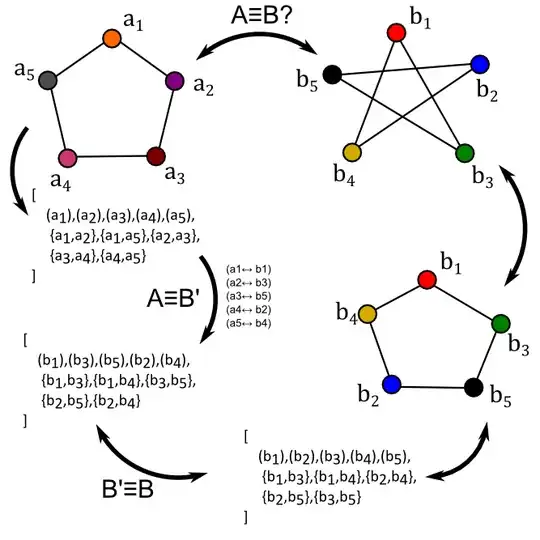

Further, it is possible for multiple graphs to produce the same diagram (except with different labels on the vertices). If you draw, for example, $G_2$, with $c_1$ in the same position as $e_1$, $c_4$ where $e_2$ was, $c_2$ where $e_3$ was, $c_5$ where $e_4$ was, and $c_3$ where $e_5$ was, and connected up the adjacent vertices with line segments, it would come out to be the same diagram as the one for $G_1$, with different labels.

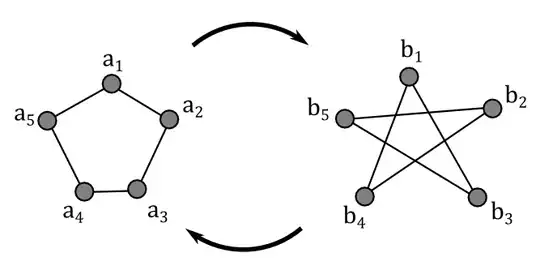

In that sense, we see that $G_1$ and $G_2$ are structurally the same graph, even though they share no vertices or edges! So, pictures introduce unnecessary variety through muddling up the positions of vertices, and the set definition of graphs introduce unnecessary variety by allowing label substitutions which don't affect the actual structure of the graph. How do we talk about two graphs being the same, in a way that doesn't throw up a false negative when the points are moved or renamed?

Enter, stage left, the concept of a graph isomorphism. If we have graphs $(V_1, E_1)$ and $(V_2, E_2)$, a graph isomorphism is a bijection $f : V_1 \to V_2$ with the property that $\{v, w\} \in E_1 \iff \{f(v), f(w)\} \in E_2$. So, the function preserves adjacency.

Two graphs are "the same" when an isomorphism exists between them. The isomorphism deals purely with the set definition of graphs (and hence doesn't care how you draw them), but will still exist even if you rename the vertices. We can therefore see that $G_1$ and $G_2$ are isomorphic, with an isomorphism as described above. The way I wrote $G_1$ and $G_2$ exposes this isomorphism clearly as well.

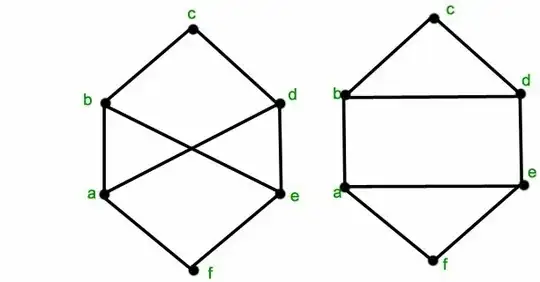

How can you tell that the other pair of graphs is not isomorphic? I think Travis covers this well in his answer. In the graph on the right, there are three vertices, e.g. $b, c, d$, such that any pair of them is an edge in the graph, i.e. $\{b, c\}, \{c, d\}, \{b, d\}$ are elements of the edge set. If an isomorphism $f$ existed, there would need to be points $f(b), f(c), f(d)$ such that $\{f(b), f(c)\}, \{f(c), f(d)\}, \{f(b), f(d)\}$. No such points $f(b), f(c), f(d)$ exist in the first graph (via quick exhaustive search), so no isomorphism exists. This implies that there's no way to rearrange the vertices from one diagram (and change their labels) to form the other diagram.

Summary (or tl;dr):

- Graphs are defined using sets, not pictures!

- The same graph may be drawn in many ways, so don't get distracted by vertices moving!

- Isomorphisms don't care about the names of the vertices or their positions.

- To see why the first pair are isomorphic, but the second pair aren't, see Travis's answer.

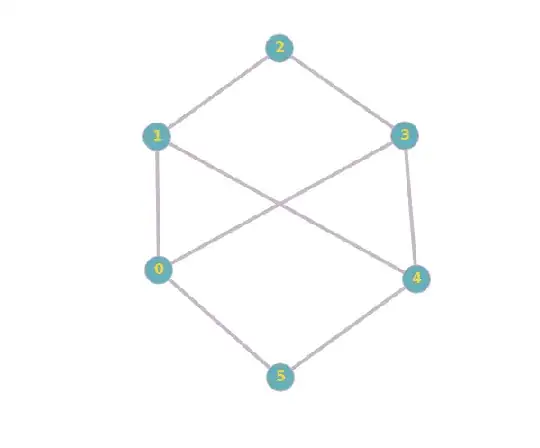

And these two aren't isomorphic:

And these two aren't isomorphic: