Assume first that $q$ is a quadratic residue modulo $p$.

By Misha Lavrov's answer we can then assume that $q=1$. We are interested in the behavior of the iterates of

$$

f(x):=\frac12\left(x+\frac1x\right).

$$

Consider the Möbius transformation from the set $P=\Bbb{F}_p\cup\{\infty\}$ to itself

$$

\mu(t):=\frac{t+1}{t-1}.

$$

We see that

$$

\begin{aligned}

f(\mu(t))&=\frac12\left(\frac{t+1}{t-1}+\frac{t-1}{t+1}\right)\\

&=\frac{t^2+1}{t^2-1}\\

&=\mu(t^2).

\end{aligned}

$$

This means that, up to conjugation by $\mu$, the mapping $f$ is just squaring in the set $P$. Therefore $f$ and squaring produce isomorphic graphs of transitions.

What happens in the set $P$ when we iteratedly square elements was studied in this thread (apologies for blowing my own trumpet to this extent). Anyway, we can say the following:

Assume $q$ is a quadratic residue. Write $p-1=2^m a,$ where $a$ is odd. Then

after $m$ iterations of $f$ the set of images has stabilized. Call this set $S$. Then further iterations will just permute the set $S$. The cycle structure of a single iteration on set $S$ can be gotten by looking at what happens with multiplication by two modulo $a$.

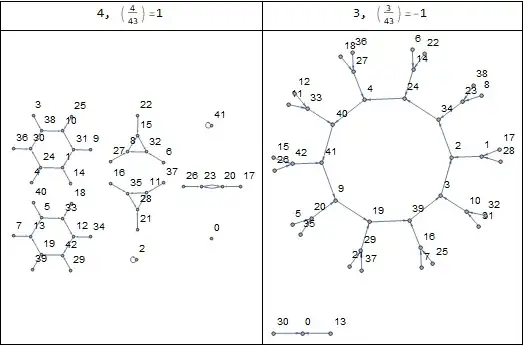

As an example let's consider the case $p=43$. This time $m=1, a=21$. Modulo $21$ multiplication by two produces the cycles

$$

(0)(1,2,4,8,16,11)(3,6,12)(5,10,20,19,17,13)(7,14)(9,18,15).

$$

Indeed, we see two 6-cycles, two 3-cycles and a single 2-cycle in Sangchul Lee's image of this graph.

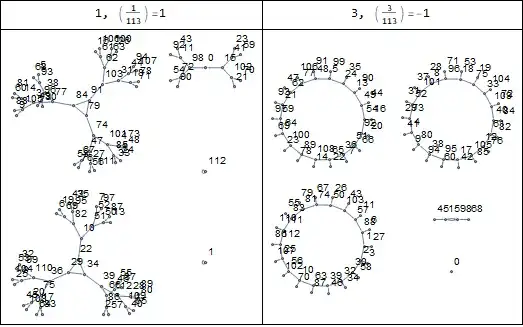

On the other hand, with $p=113$ we get $p-1=2^4\cdot7$. This explains why we get the reverse of binary branching up to depth four, and then modulo $a=7$ we see the cycles

$$

(0)(124)(365).

$$

When $q$ is not a square of an element of $\Bbb{F}_p$ the situation is a little bit different. To apply the above ideas we also work inside the quadratic extension field $\Bbb{F}_p(\sqrt{q})$.

This time we are interested in the iterations of

$$

f(x)=\frac12\left(x+\frac q x\right).

$$

As above, we see that with (as observed by Sangchul Lee in a comment to the first part) the Möbius transformation

$$

\mu_q(t)=\sqrt q\frac{t+1}{t-1}

$$

we still get the squaring rule

$$

f(\mu_q(t))=\mu_q(t^2).

$$

A difference comes from selecting an appropriate set for the parameter $t$ to range over.

The question specifies that

$$

x=\mu_q(t)\qquad(*)

$$

should range over $x\in\Bbb{F}_p$. Solving for $t$ from the equation $(*)$ gives

$$

t=\frac{x+\sqrt{q}}{x-\sqrt{q}}.

$$

Lemma. When $x$ ranges over $\Bbb{F}_p\cup\{\infty\}$ the fraction

$t=(x+\sqrt q)/(x-\sqrt q)$ ranges over the multiplicative group of norm

one elements of $\Bbb{F}_{p^2}$. In other words,

$$

S:=\left\{\frac{x+\sqrt{q}}{x-\sqrt{q}}\bigg\vert\,x\in\Bbb{F}_p\cup\{\infty\}\right\}

=\{z\in\Bbb{F}_{p^2}\mid z^{p+1}=1\}.

$$

Proof.

The non-trivial automorphism of the field $\Bbb{F}_{p^2}$ is clearly

$$F:a+b\sqrt q\mapsto a-b\sqrt q.$$

On the other hand, by the well known Galois theory of finite fields, $F$ must be the Frobenius automorphism and we also have $F(z)=z^p$. In particular, $(x\pm\sqrt q)^p=x\mp\sqrt q$ for all $x\in\Bbb{F}_p$. Therefore, if $z=(x+\sqrt q)/(x-\sqrt q)$ we have

$$

z^p=F(z)=\frac{x-\sqrt q}{x+\sqrt q}=\frac 1z.

$$

This implies that $z^{p+1}=1$. Because the multiplicative group $\Bbb{F}_{p^2}^*$ is cyclic of order $p^2-1=(p-1)(p+1)$, the equation $z^{p+1}=1$ has $p+1$ solutions in $\Bbb{F}_{p^2}$. Different choices of $x$

lead to different values for $z$, so we have found all those solutions. QED.

The rest is then easy. We know that $S$ is a cyclic group of order $p+1$.

Repeating the earlier argument we arrive at the following description:

Assume that $q$ is a quadratic non-residue. Write $p+1=2^\ell b$, $b$ odd.

Then after $\ell$ iterations the image of $f$ has stabilized. Any further iterations of $f$ will permute this set with the same cycle structure as

multiplication by $2$ permutes the residue classes modulo $b$.

As an example consider the case $p=43$, $q=3$ from the top right image in Sangchul Lee's question. Here $p+1=44=2^2\cdot11$. Therefore the graph has two stages of binary branch convergence. Modulo $b=11$ multiplication by two looks

like

$$(0)(1,2,4,8,5,10,9,7,3,6)$$

explaining the emergence of a 10-cycle (and a fixed point) seen in the image.

Similarly, when $p=113$, we get $p+1=114=2\cdot57$. After a single step of two branches converging we are left to study the cycles of multiplication by two modulo $57=3\cdot19$. Two is a primitive root modulo $19$, so it follows that

we get three 18-cycles, a fixed point $0$, and a 2-cycle $(19,38)$. Again, in accordance with the graph in the bottom right.

Remark: I cooked up an analogue of the Lemma once to study certain character sums. A colleague used it to study correlation properties of certain families of sequences.

See this MathOverflow thread, where Michael Zieve does something similar. Also see Peter Mueller's answer for a generalization. So I am not the inventor. I simply had not seen it before. Anyway, the Lemma is totally analogous to the fact that

$$

\left\{\frac{x+i}{x-i}\in\Bbb{C}\bigg\vert\,x\in\Bbb{R}\cup\{\infty\}\right\}

$$

is the unit circle of the complex plane.