From Understanding Machine Learning: Theory and Algorithms:

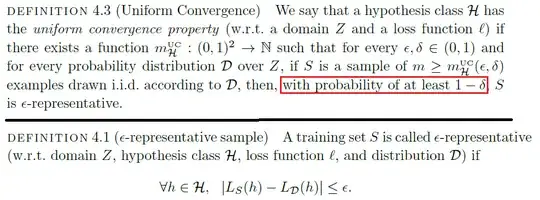

What does the phrase in the red box below mean in terms of set theory?

I see that it means for every $h \in H$ we have $D(|L_s(h) - L_D(h)| \le \epsilon) \ge 1 - \delta$.

But how is $|L_s(h) - L_D(h)| \le \epsilon$ a random variable?

If it's a random variable then in should be of the form $\{a \in A : X(a) \le \epsilon\}$ where $X = |L_s(h) - L_D(h)|$ and $A$ is the sample space.

But what in this definition is $A$?

I know that $L_D(h) = \Bbb E_{z \text{~}D}[l(h,z)] = \sum_{z \in Z}l(h,z)D(z)$ and $L_S(h) = \frac{1}{m}\sum_{z_i \in S} l(h,z)$ where:

$l(h,z)$ is a loss function, $D$ is the distribution on $Z$, and $S$ is a training set.

It says the probability of $S$ being $\epsilon$ representative is $1-\delta$. Which means $P(X \le \epsilon) \ge 1 - \delta$ where $X = L_S(h) - L_D(h)$. But $X \le \epsilon$ is an event. Which means it's a subset of some sample space of things. So it's of the form ${a \in A : X(a) < \epsilon }$. What are the things that you substitute into $X$ so say you measure the error of? X by itself is the error between $h$ trained on $S$ and the mean error from $h$ on new data.

– Oliver G Jan 19 '19 at 20:37