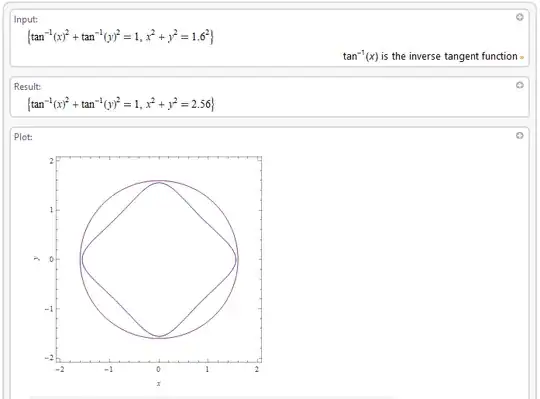

Seems like the smallest circle is always tangent at $x=0$ or $y=0$. So you can put $\arctan(x)^2=a$ and solve $x=\tan\sqrt a$. This would be the radius.

Edit: let's make it rigorous.

Let's maximize $x^2+y^2$ with the constraint $\arctan(x)^2+\arctan(y)^2=a$. By symmetry we can work in the positive quadrant. With Lagrange multipliers we find

$$

\left(\frac{\arctan(x)}{1+x^2},\frac{\arctan(y)}{1+y^2}\right)

= \lambda (x,y),

$$

therefore (unless $x=0$ or $y=0$, which are easily seen to be stationary points) we have

$$

\frac{\arctan(x)}{(1+x^2)x} = \frac{\arctan(y)}{(1+y^2)y}.

$$

We want to show that the only possibility is $x=y$. The we need an argument to say that this is a minimum and not a maximum.

As a matter of fact, the function $\frac{\arctan(x)}{(1+x^2)x}$ is decreasing, so this shows that $x=y$ are the only solutions. Its derivative is in fact

$$

\begin{split}

\frac{d}{dx}\frac{\arctan(x)}{(1+x^2)x} &=

\frac{2}{x

\left(x^2+1\right)^2}-\frac{2 \arctan(x)}{x^2

\left(x^2+1\right)}-\frac{4 \arctan(x)}{\left(x^2+1\right)^2} \\

&< \frac{2}{x

\left(x^2+1\right)^2}-\frac{2 \arctan(x)}{x^2

\left(x^2+1\right)} \\

&= -2 \frac{(1+x^2)\arctan(x)-x}{(x+x^3)^2} < 0.

\end{split}

$$

You may rightfully wonder why is $(1+x^2)\arctan(x)-x>0$? Well, it vanishes at $0$ and its derivative is $2x\arctan(x)>0$.

So, why is $x=y$ a minimum? Well, we just need to compare it with the point at $y=0$.

The values of $x^2+y^2$ at the two points are respectively $2(\tan\sqrt{a/2})^2$ and $(\tan\sqrt a)^2$. Since the function $f(t)=(\tan\sqrt t)^2$ is convex and vanishes at $0$, it is superadditive, implying that $2f(a/2)\leq f(a)$.

Bonus

I'd like to add one little piece, related to proving that $(1+x^2)\arctan(x)-x$ is increasing. The insight is that it is of the form $\frac{g(x)}{g'(x)}-x$ with $g$ concave. Then it's derivative is $-\frac{g(x)g''(x)}{g'(x)^2} \geq 0$. I don't know if this general detail might be useful to someone.