Following is an algebraic proof of the statement. To make the algebra manageable. We will choose a coordinate system where $A$ is the origin and identify the euclidean plane with the complex plane.

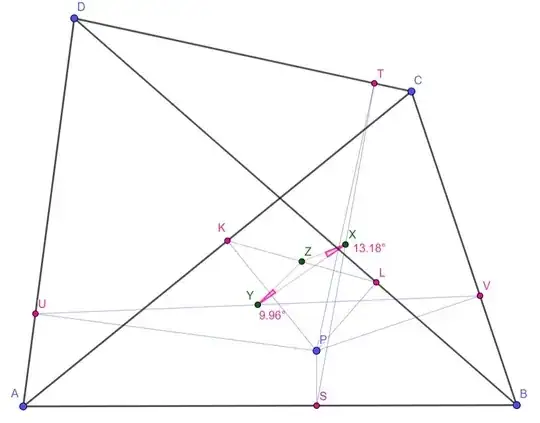

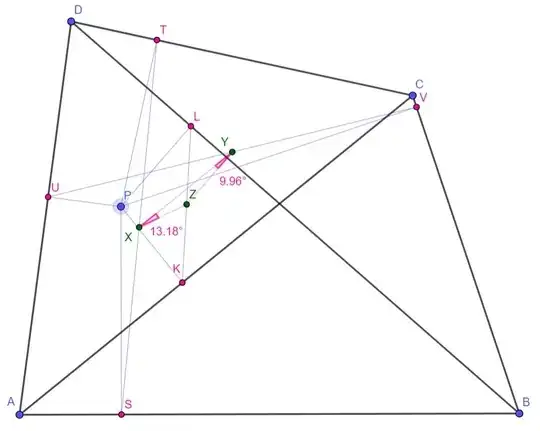

Let $p, z_1,z_2,z_3, u_1, v_1, w_1, w_2, w_3$ be the complex numbers corresponds to $P,

B,C,D,S,T,X,Z,Y$ respectively.

Any line $\ell \subset \mathbb{C}$ can be represented by a pair of complex number, a point $q \in \ell$ and a $t$ for its direction. Points on $\ell$ has the form $q + \lambda t$ for some real $\lambda$. In order for this point to be the projection of $p$ on $\ell$, we need

$$\Re( ( q + \lambda t - p )\bar{t}) = 0\quad\implies\quad\lambda = \frac{\Re((p - q)\bar{t})}{t\bar{t}}

$$

The projection of $p$ on line $\ell$, let call it $\pi_\ell(p)$, will be given by the formula

$$\pi_{\ell}(p) = q + \frac{(p-q)\bar{t} + (\bar{p}-\bar{q})t}{2\bar{t}} = \frac{q+p}{2} +\frac12(\bar{p} - \bar{q})\frac{t}{\bar{t}}\tag{*1a}$$

In the special case that $q = 0$, this reduces to

$$\pi_{\ell}(p) = \frac{p}{2} + \frac12\bar{p}\frac{t}{\bar{t}}\tag{*1b}$$

Apply $(*1b)$ and $(*1a)$ to $S$ and $T$, we get

$$u_1 = \frac{p}{2} + \frac12\bar{p}\frac{z_1}{\bar{z}_1}

\quad\text{ and }\quad

v_1 = \frac{p + z_2}{2} + \frac12(\bar{p} - \bar{z}_2)\frac{z_2 - z_3}{\bar{z}_2 - \bar{z}_3}

$$

Combine them and simplify, we get

$$

w_1 = \frac{u_1+v_1}{2} =

\frac{p}{2} + \frac14\bar{p}

\underbrace{\left(\frac{z_1}{\bar{z}_1} + \frac{z_2-z_3}{\bar{z}_2 - \bar{z}_3}\right)}_{A_1}

+

\frac14

\underbrace{\left(\frac{z_3\bar{z}_2 - z_2\bar{z}_3}{\bar{z}_2 - \bar{z}_3}\right)}_{B_1}$$

Let's call the two coefficients in parentheses as $A_1$ and $B_1$. By similar argument,

we can derive corresponding formula for $w_2$ and $w_3$. In general, we have

$$w_i =

\frac{p}{2} + \frac14\bar{p} A_i + \frac14 B_i

\quad\text{ where }\quad

\begin{cases}

\displaystyle\;A_i = \frac{z_i}{\bar{z}_i} + \frac{z_j-z_k}{\bar{z}_j - \bar{z}_k}\\

\displaystyle\;B_i = \frac{z_k\bar{z}_j - z_j\bar{z}_k}{\bar{z}_j-\bar{z}_k}

\end{cases}

$$

for $(i,j,k)$ running over cyclic permutations of $(1,2,3)$.

Given any two triangle $M$, $N$ with vertices $m_1,m_2,m_3$ and $n_1,n_2,n_3$. They are similar (with matching angles) if they have the same cross-ratio

$$\frac{m_3-m_1}{m_2-m_1} = \frac{n_3-n_1}{n_2 - n_1}$$

In order for the angles of triangle $XYZ$ to be independent of $P$, we need the cross ratio

$$\frac{w_3 - w_1}{w_2-w_1}

= \frac{(A_3 - A_1)\bar{p} + (B_3 - B_1)}{(A_2-A_1)\bar{p} + (B_2-B_1)}$$

to be independent of $p$. This is equivalent to

$$\frac{A_3-A_1}{A_2-A_1} = \frac{B_3-B_1}{B_2-B_1}

\iff \left|\begin{matrix}A_3 - A_1 & B_3 - B_1 \\ A_2 - A_1 & B_2 - B_1\end{matrix}\right| = 0$$

At the end, it comes down whether following complicated determinant evaluates to zero

$$

\left|\large\begin{matrix}

1 & \frac{z_1}{\bar{z}_1} + \frac{z_2-z_3}{\bar{z}_2 - \bar{z}_3}

& \frac{z_3\bar{z}_2 - z_2\bar{z}_3}{\bar{z}_2 - \bar{z}_3}\\

1 & \frac{z_2}{\bar{z}_2} + \frac{z_3-z_1}{\bar{z}_3 - \bar{z}_1}

& \frac{z_1\bar{z}_3 - z_3\bar{z}_1}{\bar{z}_3 - \bar{z}_1} \\

1 & \frac{z_3}{\bar{z}_3} + \frac{z_1-z_2}{\bar{z}_1 - \bar{z}_2}

& \frac{z_2\bar{z}_1 - z_1\bar{z}_2}{\bar{z}_1 - \bar{z}_2} \\

\end{matrix}\right|

\stackrel{?}{=} 0

$$

If one multiply

first row by $\bar{z}_1(\bar{z}_2 - \bar{z}_3)$,

second row by $\bar{z}_2(\bar{z}_3 - \bar{z}_1)$

third row by $\bar{z}_3(\bar{z}_1 - \bar{z}_2)$

and sum them together, one obtain an zero row!

This means above determinant vanishes and the cross-ratio $\frac{w_3 - w_1}{w_2-w_1}$ is independent of $p$.

This verify the angles in $\triangle XYZ$ doesn't depend on location of $P$.

With help of an CAS, one also obtain

$$\frac{w_3-w_1}{w_2-w_1} = \frac{A_3-A_1}{A_2-A_1} = \frac{B_3-B_1}{B_2-B1}

= \frac{(\bar{z}_3 - \bar{z}_1)\bar{z}_2}{(\bar{z}_2-\bar{z}_1)\bar{z}_3}$$

The last expression is complex conjugate of a cross-ratio of the 4 numbers $(0,z_1,z_2,z_3)$. With this, we can deduce the angles of $\triangle XYZ$

from the angles among the sides/diagonals of quadrilateral $ABCD$.

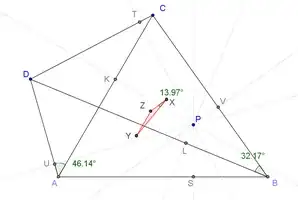

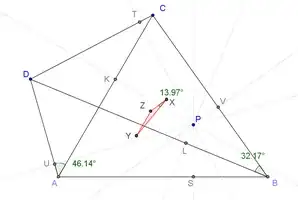

As an example, in the configuration below, we have

$$\angle ZXY (\approx 13.97^\circ) = \angle CAD (\approx 46.14^\circ) - \angle CBD (\approx 32.17^\circ)$$

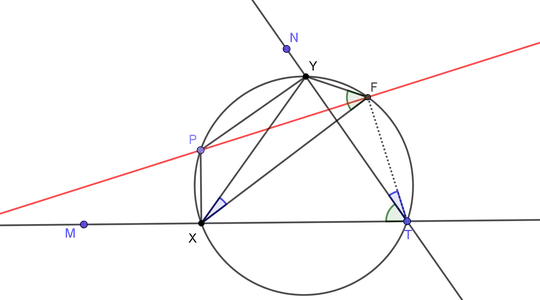

Please note that when quadrilateral $ABCD$ is cyclic, $\angle CAD = \angle CBD$. In such cases, triangle $XYZ$ degenerate into a line segment (as first pointed out by @g.kov in comment).

I hope this can inspire someone to discover a more geometric proof of this (in particular, above relations among the angles).