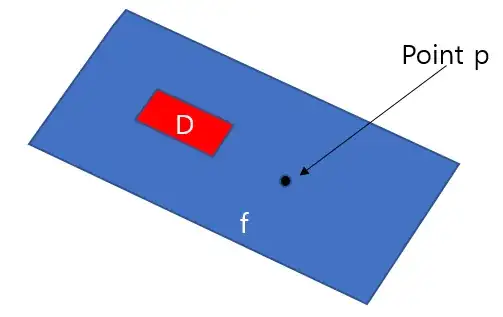

$$f : x_{1}+...+x_{n}=s $$ $f$ is an n dimensional hyperplane and $x_{1},...,x_{n}$ are elements of a vector X.

All the elements of X have inequality constraints which are given below.

$$L_{1} \leq x_{1} \leq B_{1}$$

$$L_{2} \leq x_{2} \leq B_{2}$$

$$...$$

$$L_{n} \leq x_{n} \leq B_{n}$$

Let's say there is a domain $D$ made by $f$ and the given inequality constraints.

(Assume that $D$ must exist.)

Also, there is a point $P$ on the $f$ but not in the domain $D$.

Here, my assumption is :

"There is a unique Minimum Euclidean distance between point $P$ and domain $D$."

I'm convinced that my assumption is true but have no idea how to prove this.

Any ideas?

Thanks.

M.Kim