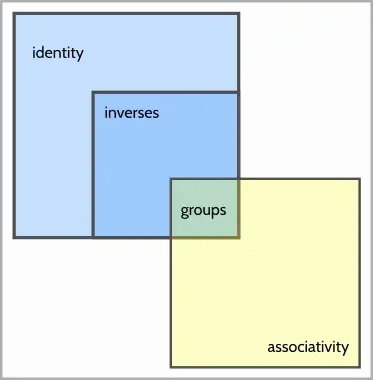

Update: The proof I gave that you can't have inverses at all assumed associativity. Out of the three properties in question (identity, inverses, associativity), you can have any combination whatsoever as long as it does not have both inverses and associativity.

This change can be made without affecting the identity, though it doesn't have to. As an example, consider the additive group $\mathbb{Z}_2$ with $1+1=1$ instead of $1+1=0$. By inspection of the 3 relevant cases, there is still an identity in this set and operation even though rows and columns have duplicated information.

That isn't mandatory. The offending definition could just as well have been $0+1=0$, with nothing else changed. One could easily verify that the resulting set and operation do not have an identity.

If there is not an identity, inverses don't exist. At least, the definitions of inverse that I'm familiar with explicitly define such a thing in terms of an identity.

If there IS an identity, inverses still don't exist. Consider (with multiplicative notation and an identity of $e$) the equation $ax=bx$ corresponding to a row with duplicates if $a\neq b$. Note that if inverses existed we would have $ae=be$, but since $e$ is the identity we have $a=b$, violating $a\neq b$.

Associativity can go either way. The object $\mathbb{Z}_2$ with $1+1=1$ is associative and even has an identity. As far as modifications to $\mathbb{Z}_2$ are concerned, there are non-associative options as well (like all additions being $0$ except $0+1=1$), but none of them have a proper identity.

With slightly more elements, we can lose associativity and retain the identity. Consider the set $\{0,1,2\}$ with $0$ as an identity, $1+1=0$, and $2+1=0$. Note that $$\begin{aligned}2+(1+1)&=2+0\\&=2\neq1\\&=0+1\\&=(2+1)+1.\end{aligned}$$ The remaining operations can be defined however you want, and this Cayley table still corresponds to a set with an identity and without associativity.