Using ideas described in Gowers blog post about Zorn's Lemma we will define a subadditive function $f\colon ℝ_+ → ℝ_+$ with the desired property.

Let $\mathcal{B} = \{e_β\}_{β ∈ B}$ be a Hamel Basis of $ℝ$ over the field of rationals. Since $\mathcal{B}$ remains a Hamel Basis when we replace $e_β$ with $q\cdot e_β$ where $q$ is non-zero rational, we can assume that all $e_β > 0$ and there is $\{ e_n \}_{n \in ℤ_+} \subset \mathcal{B}$ such that $2^{-(n+1)}< e_n<2^{-n}$.

For each $n \in ℤ_+$ pick $a_n,b_n \in \mathbb{Q}_+$ such that $1 - 2^{-n} < a_n e_n < b_n e_n < 1$. Note $a_n e_n → 1$. Let $\text{span}(e_n) = \{ q e_n \mid q \in \mathbb{Q}_+\}$ and define a piecewise linear function $f_n \colon \text{span}(e_n) \to \text{span}(e_n)$ passing thru there points $(0,0), (e_n, a_n e_n)$ and $(b_n e_n, b_n e_n)$:

$$

f_n(x) =

\begin{cases}

a_n x, & 0 < x ≤ e_n,\\

\frac{b_n-a_n}{b_n-1}x + e_n \frac{b_n(a_n-1)}{b_n-1}, & e_n < x ≤ b_n e_n,\\

x, & b_n e_n < x.

\end{cases}

$$

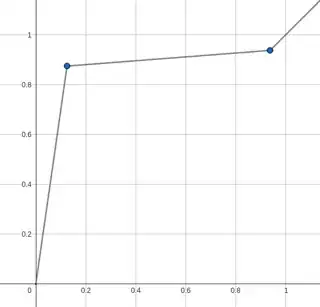

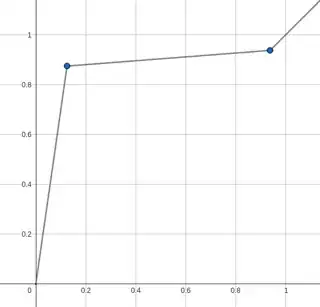

(Pedantical note: Point $(0,0)$ does not belong to the graph of $f_n$, but this framing makes the idea behind $f_n$ clear.) To familiarize with $f_n$'s here is graph of $f_3$:

Just keep in mind that domain and codomain are not $ℝ_+$ but $\text{span}(e_3)$.

Note that $f_n$ is well-defined since we always multiply $e_n$ by some positive rational, so the codomain is indeed $\text{span}(e_n)$. It's a bijection. Moreover, $f_n$ is subadditive. We verify this by boring casework at the end of this proof, but the upshot is this: In each case, we either use the fact that $f_n|_{(0,b_ne_n]}$ is concave and positive and hence subadditive, or that the graph of $f_n$ is above the identity, that is $x \leq f_n(x)$.

Finally, we can define $f\colon ℝ_+ → ℝ_+$ as

$$

f(x) =

\begin{cases}

f_n(x), & x \in \text{span}(e_n),\\

x, & \text{otherwise.}

\end{cases}

$$

This is a well-defined function because each $x \in ℝ_+$ has a unique representation in terms of Hamel Base $\mathcal{B}$.

Function $f$ is a bijection. Clearly, $\liminf_{x → 0_+} f(x) = 0$ since it acts like the identity function for almost all inputs, and otherwise $f_n ≥ 0$. To find $\limsup$, first note that on $(0, 1]$, $f$ is bounded from above by $1$. Secondly, $e_n → 0$ and $1>f(e_n) > a_n e_n > 1-2^{-n}$, so $f(e_n) \to 1$. Hence, $\limsup_{x\to 0^+} f(x) = 1$ as required.

It remains to show that $f$ is subadditive. Take any $x,y \in ℝ_+$.

If $x,y \in \text{span}(e_n)$ for some $n$. Then $x+y \in \text{span}(e_n)$ and subaddivity of $f$ follows from the subadditivity of $f_n$.

If $x \in \text{span}(e_n)$ for some $n$ but $y \not\in \text{span}(e_n)$ (or vice versa). Then $f(x+y) = x+y$. Because $f_n(x) ≥ x$ as well as $f(y) ≥ y$ we have $f(x) + f(y) = f_n(x) + f(y) ≥ x + y = f(x+y)$.

If none of the above cases are true, then $f(x+y) = x+ y = f(x) + f(y)$.

We show that the function $f_n$ is subadditive. Take $x,y \in \text{span}(e_n)$. WLOG assume that $x \leq y$. If $x,y$ and $x+y$ are in one of three intervals $(0, e_n]$, $[e_n, b_n e_n]$, or $[b_n e_n, \infty)$, then the condition holds, since a restriction of $f_n$ to each of those intervals is additive. It remains to show what happens in "mixed" cases.

When $x,y≤ e_n$ and:

- (A1) $e_n < x+y ≤b_n e_n$.

- (A2) $b_n e_n < x+y$.

When $x≤e_n<y$ and:

- (B1) $y,x+y ≤ b_ne_n$.

- (B2) $y≤ b_ne_n < x+y$.

- (B3) $b_ne_n < y, x+y$.

When (C) $e_n < x,y ≤ b_n e_n < x+y$.

When (D) $e_n < x <b_n e_n< y, x+y$.

Note that $f_n|_{(0, b_ne_n]}$ is concave and positive. Hence subadditive. Thus subadditivity for cases A1 and B1 is proven. Now assume A2 holds. Then

$$

f_n(x+y) = x+ y ≤ f_n(x)+f_n(y),

$$

since $f_n$ is on or above identity. The same reasoning will work for the rest of the cases.

□