Here's the insane approach ... Let's find the equation of the Flower curve!

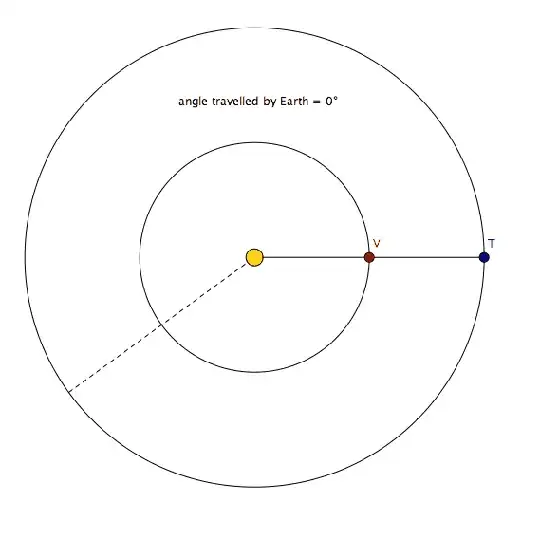

The curve is the envelope of line segments determined by the two planet-points, which we can parameterize as

$$P = p \,( \cos 8 t, \sin 8 t ) \qquad Q = q\, ( \cos 13 t, \sin 13 t )$$

where $p$ and $q$ are the radii of the orbits. The line $PQ$ is then

$$f(t) := x \left( p \sin 8 t - q \sin 13 t \right) + y ( - p \cos 8 t + q \cos 13 t ) + p q \sin 5 t \tag{1}$$

so that

$$f^\prime(t) := x \left( 8 p \cos 8 t - 13 q \cos 13 t \right) + y \left( 8 p \sin 8 t - 13 q \sin 13 t \right) + 5 p q \cos 5 t \tag{2}$$

To derive the equation of the envelope, "all we have to do" is eliminate $t$ from $f(t)$ and $f^\prime(t)$. With lots of classical envelopes (cardioids, astroids, parabolas, etc), the elimination step is fairly straightforward. Here, with $t$ trapped inside the various sines and cosines, things are a bit complicated. It helps a bit to rewrite the equations in terms of the complex exponential, $\omega := \exp(it)$; it'll help further to define $z := x + i y$ and $\bar{z} := x - i y$. So, we make the substitutions

$$\cos kt = \frac12(\omega^k+\omega^{-k}) \qquad

\sin kt = \frac1{2i}(\omega^k-\omega^{-k}) \qquad

x = \frac12(z+\bar{z}) \qquad

y = \frac1{2i}(z-\bar{z})$$

Then $(1)$ and $(2)$ become, after clearing denominators,

$$\omega^{26} q \bar{z} - \omega^{21} p \bar{z} - \omega^{18} p q + \omega^8 p q + \omega^5 p z - q z \tag{3}$$

$$13 \omega^{26} q \bar{z} - 8 \omega^{21} p \bar{z} - 5 \omega^{18} p q - 5 \omega^8 p q - 8 \omega^5 p z + 13 q z \tag{4}$$

and now "all we have to do" is eliminate $\omega$. Again, this is conceptually straightforward: we merely invoke the method of resultants, which Mathematica graciously implements as its Resultant[] function. However, the computational complexity of resultant-finding is related to the sum of the degrees of the polynomials ---here 52--- which causes Resultant[] to bog down on my computer. Happily, I was able to get a faster implementation by having Mathematica construct the Sylvester Matrix for the polynomials, and take its determinant (which is equivalent to the resultant). The result(ant) is :

$$\begin{align}

&2814749767106560000000000 p^{36} q^{42} \\

+ &\cdots \;\text{($760$ terms)}\; \cdots \\

+ &18258084432456195379316013815625 p^{26} q^{16} z^{13} \bar{z}^{23}

\end{align}\tag{5}$$

Now, instead of restoring $z$ and $\bar{z}$ back to $x$ and $y$ form, I can use to the more-appropriate complex polar form:

$$z = r \exp(i\theta) \qquad \bar{z} = r\exp(-i\theta)$$

to get

$$\begin{align}

&15879378388503914086400000 \;\left(e^{15i\theta}+e^{-15i\theta} \right)\; p^{39} q^{24} r^{15} \\

+&\phantom{1}3 \left(e^{10i\theta}+e^{-10i\theta} \right)\;p^{26} q^{16} r^{10} (3289829448089600000000000 p^{12} q^{14} + \cdots) \\

-&12 \left(e^{5i\theta}+e^{-5i\theta} \right)\; p^{13} q^8 r^5 (1179648000000000000000 p^{26} q^{26} + \cdots) \\

-&\phantom{1}2\;(1407374883553280000000000 p^{36} q^{42} + \cdots) \\

\end{align} \tag{6}$$

Conveniently, the complex exponentials pair-up to form cosines (with a factor of $2$), so that the polar equation of the Flower of Venus has the form

$$\begin{align}

0 \;=\;\; &31758756777007828172800000 \;\cos 15\theta\; p^{39} q^{24} r^{15} \\

+&\phantom{1}6 \cos 10\theta \;p^{26} q^{16} r^{10} (3289829448089600000000000 p^{12} q^{14} + \cdots) \\

-&24 \cos 5\theta \; p^{13} q^8 r^5 (1179648000000000000000 p^{26} q^{26} + \cdots) \\

-&\phantom{1}2\;(1407374883553280000000000 p^{36} q^{42} + \cdots) \\

\end{align}\tag{$\star$}$$

Since the arguments of the cosines are all multiples of $5\theta$, the curve must have $5$-fold rotational symmetry. Easy-peasy! $\square$

Of course, this ad hoc approach doesn't provide any insights at all into why the $5$-fold symmetry appears, what happens with other "ratio differences", etc. I really just wanted to see for myself how crazy the Flower curve's equation is. I suspect that there must be a way to anticipate the symmetry from $(1)$ and $(2)$ (or $(3)$ and $(4)$) without having to actually calculate the resultant; if so, then (presumably) that strategy should apply to arbitrary ratio differences.