Based on Why do differentiating and integrating 'work'?

In differentiation, you take the gradient of a point $x$ by differentiating. To this, you take two points on the graph, one which is the point where you want to find the gradient of, and another one (which is explained later).

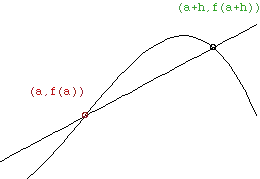

As you can see, there are two points:

$$(a,f(a)) \text{ and } (a+h,f(a+h))$$

Where $h$ is the distance between the points.

We take the gradient of these two points, and we get:

$$f'(x)=\dfrac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{(a+h)-a}$$

$$=\dfrac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{h}$$

To find the gradient of a point, we take $h$ as $h \rightarrow 0$ which gives us the gradient of the graph at $x$

So, now about integration.

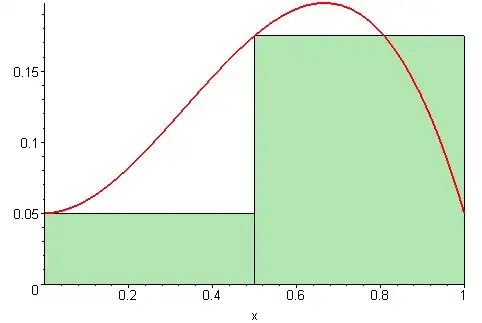

I understand that integration is using a trapezium rule to take the limit as the width of each strip $\rightarrow 0$ and the number of strips $\rightarrow \infty$

This gives us $$ \lim\limits_{n\to\infty} \sum\limits_{i=1}^n f(x_i)\Delta x_i$$

$n=$ number of strips

$\Delta x_i =$ width of strip $i$

So what is the algebraic reasoning behind this transformation of a function?

All images belong to Source