I have considered a sequence defined as follows:

$$a_{n+1}=a_n+\log a_n$$

$$a_1=2$$

Surprisingly enough, its growth is almost linear, or, more precisely, it seems that:

$$n < a_n < n^{3/2}$$

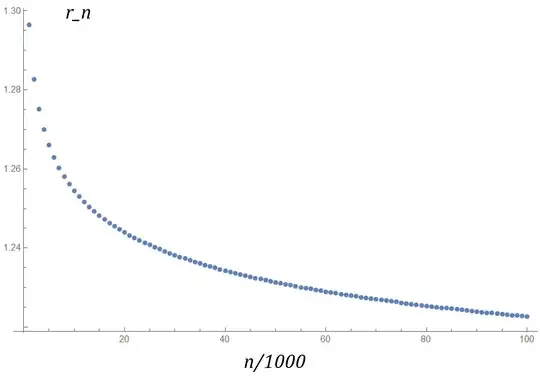

From numerical experiments, the growth rate for large $n$ is well described by a power law (as it's obvious from the previous condition), with the exponent being around $1.2$. Here's the plot of:

$$r_n=\frac{\log a_n}{\log n}$$

for $n=10^3 - 10^5$.

For larger $n$ we have, for example:

$$r_{0.5 \cdot 10^6}=1.204993305$$

$$r_{1.5 \cdot 10^6}=1.194589226$$

$$r_{4.5 \cdot 10^6}=1.185287843$$

$$r_{10 \cdot 10^6}=1.179122734$$

$$r_{20 \cdot 10^6}=1.174129607$$

Can we (1) prove that the sequence obeys a power law for $n \gg 1$ and (2) find the value of $r_{\infty}$?

Edit

If, as Did says in the comments, the sequence actually obeys another law:

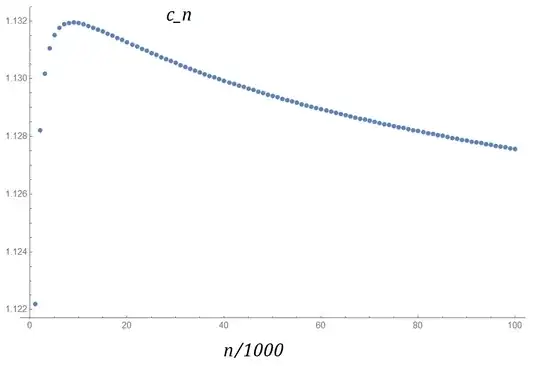

$$a_n \asymp c n \log n$$

Then it would be interesting to prove and especially find $c$.

From experiments:

$$c_{10 \cdot 10^6}=1.113128774$$

$$c_{20 \cdot 10^6}=1.111029684$$

And the plot for $n=10^3 - 10^5$:

Professor Vector suggested that $c_{\infty}=1$, which is possible even though convergence is really slow.

Update:

In a linked question I prove (kind of) that the following inequality holds for $n \geq 2$:

$$a_n \leq (n+1) \left( \ln (n+1) + \ln \ln (n+1) \right)$$

This bound is quite tight.

First of all, from your inital condition $a_1=2$ it is obvious that $a_n\rightarrow +\infty$.

Furthermore, approximate $a_{n+1}-a_n\approx a'_{n}$ (we will justify this in hindsight). This yields ($n\rightarrow x,,a_n\rightarrow y(x)$) $$ y'(x)=\log(x) \rightarrow x=\int\frac{dy}{\log(y)} $$

which might be implicitly solved in terms of the logarithmic integral $\text {li}(z)$

$ x=\text {li}(y)+C $

– tired Feb 25 '18 at 22:26$$ x\sim\frac{y}{\log(y)}+O\left(\frac{1}{\log(y)}\right) $$

or

$$ y(x)\sim -x W_{-1}\left(-\frac{1}{x}\right) $$

– tired Feb 25 '18 at 22:26$$ y(x)\sim x\log(x) $$

as expected.

Now, $y^{(n)}(x)\sim x^{-n-1}\ll y'(x) = \log(x)+1$ which justifies our inital approxmation (the higher order corrections to the difference between $\Delta a_n$ and $a'_{n}$ negligible). So

$$ a_n\sim n \log(n)\quad \text{as} ,,n\rightarrow \infty $$

– tired Feb 25 '18 at 22:26