The biharmonic equation takes two boundary conditions. Typical choices:

- Prescribe both $u$ and $\partial u /\partial n$ on the boundary.

- Prescribe both $u$ and $\Delta u$ on the boundary: this is convenient for splitting the problem in two Poisson' equations $\Delta u = v$, $\Delta v = f$, but is not very natural.

The first choice, with homogeneous boundary conditions, simply means we look for

a solution in $H^2_0(U)$, which is strictly smaller than $H^1_0(U)\cap H^2(U)$. The post Unique weak solution to the biharmonic equation is very relevant here.

The second choice, with homogeneous conditions, leads to $v\in H^1_0(U)$ and subsequently $u\in H^1_0(U)\cap H^3(U)$ which is slightly weird (and also smaller than $H^1_0(U)\cap H^2(U)$).

The only natural situation that I can think of where you get $H^1_0(U)\cap H^2(U)$ is when you prescribe homogeneous Dirichlet and non-homogeneous Neumann condition, $\frac{\partial u}{\partial n}=g$ on $\partial\Omega$. Then one has to require $g$ to be compatible with the desired regularity: there must be some function $w\in H^1_0(U)\cap H^2(U)$ such that $\frac{\partial w}{\partial n}=g$. Writing $u=w+\tilde u$, you then reduce the problem to the homogeneous case: $\tilde u \in H^2_0(U)$ with $\Delta^2 u = f - \Delta^2 w$.

What are those function spaces?

You also asked for an explanation of that intersected function space. The part $H^2$ indicates the interior regularity and says nothing about boundary behavior. The part $H^1_0$ indicates vanishing of $1$st order on the boundary; intuitively, it's $u=0$ but not necessarily $\partial u/\partial n=0$. Recall that $H^k_0(U)$ consists of all limits of smooth compactly supported functions in $H^k(U)$. Being compactly supported means the derivatives of all orders vanish on the boundary. But the "limits of" part is governed by the index $k$ which indicates how much of that vanishing is actually preserved.

Most notably, $u\in H^2_0(U)$ implies $\nabla u\in H^1_0(U)$ while $u\in H^2_0(U)\cap H^1_0(U)$ only implies $\nabla u \in H^1(U)$.

Here is an illustration of these function spaces, with the domain $U$ being the interval $(-1,1)$.

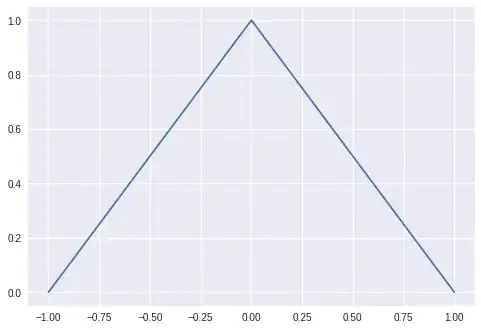

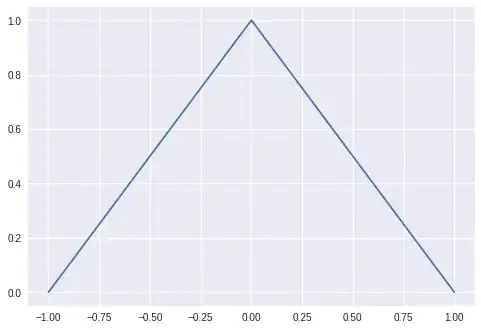

$H^1_0$ but not $H^2$

Vanishes on the boundary like $H^1_0$ indicates, but interior smoothness is low.

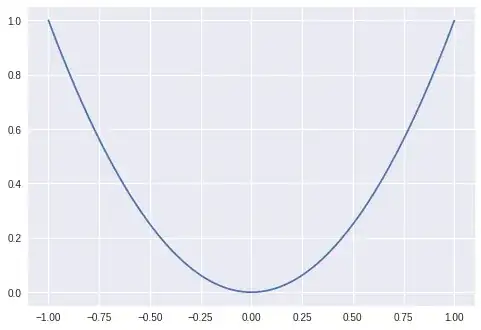

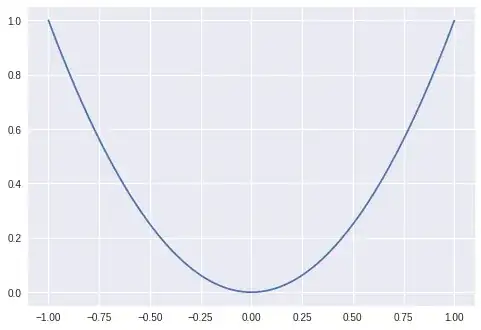

$H^2$ but not $H^1_0$

Smooth but no vanishing on the boundary.

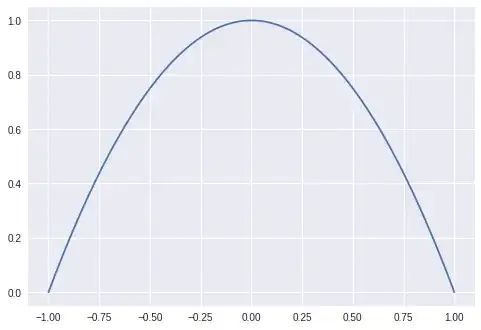

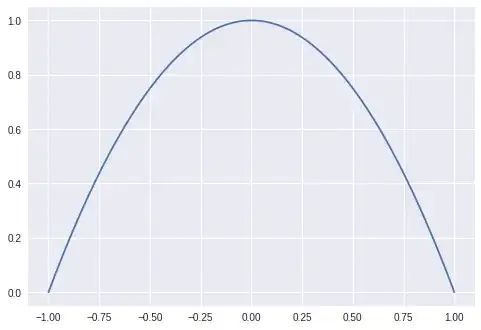

$H^2$ and $H^1_0$ but not $H^2_0$

Vanishes on the boundary like $H^1_0$ indicates, and is smooth inside. However, the derivative does not vanish on the boundary: the gradient is not in $H^1_0$.

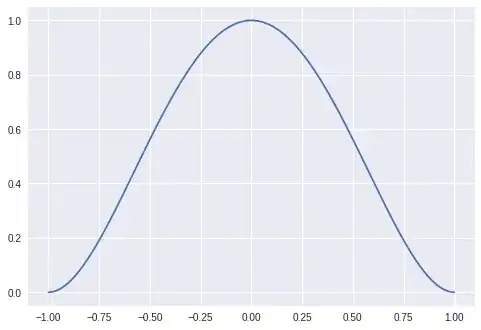

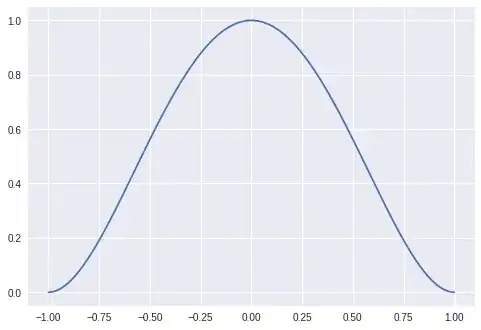

$H^2_0$

The function is "clamped" on the boundary. I'd say this is a natural space in which to study the biharmonic equation.