In $\Bbb R^3$ we have a closed convex polyhedron $P$ with triangularised faces (you may assume it's symmetric about the origin for simplicity.), and a point light source $s\notin P$. Let $F_{1,\cdots, m}$ be all of $P$'s faces, and $\pi_i$ be the plane that passes through $F_i$ respectively. Each $\pi_i$ cuts $\Bbb R^3$ into two open regions one of which contains the interior of $P$ while the other doesn't intersect $P$. For each $i$, we call the open region that doesn't intersect $P$ as $R_i$. Then we know that a face $F_i$ is lighted by $s$ if and only if $s\in R_i$. Now consider the collection $\mathcal F_s$ of all faces that are lighted by $s$.

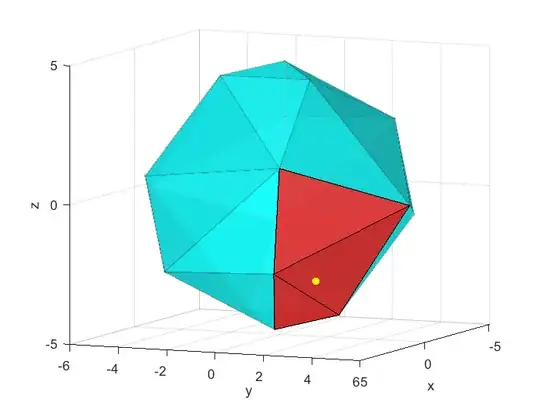

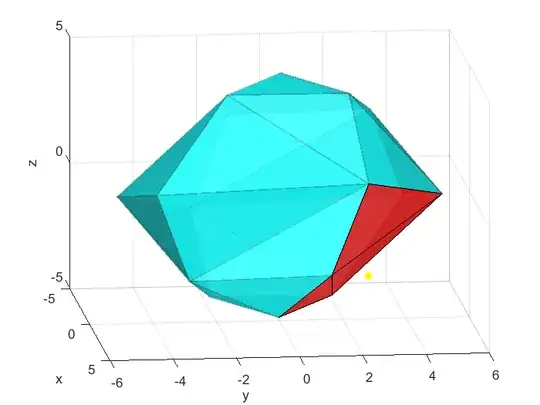

An illustration made in Matlab where the yellow point indicates the light source and faces coloured red are lighted faces (viewed from two different angles):

I have to show that $\mathcal F_s$ is entirely connected, in the sense that any face in $\mathcal F_s$ must share an edge with at least one another face in $\mathcal F_s$ (which is slightly stronger than path connectedness, because in this case two faces connected only by a single point are not considered as connected), and that the union of all faces in $\mathcal F_s$ is simply connected.

This is geometrically intuitive, but the proof turns out extremely hard for me. Having been working on it for a whole week, I still get virtually nothing of value. Could anybody help?

PS: for what it's worth, it's 2D analog is very easy to prove, because edges of a convex polygon form a loop and we can make sense of a "direction" on it. But in 3D, the connectivity between faces is much more complicated. So I don't think there is an easy extension from 2D to 3D.