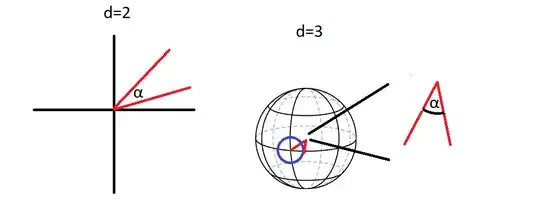

A rotation in (2n+1)-dimensions has a real eigenvalue $\pm 1$, its eigenvector spans an invariant 1-d axis subspace. Except for dimension 3 with its single parameter of an angle determining the rotation matrix in the 2d-plane orthogonal to the axis, in higher dimensions the 2n-dimensional subspace orthogonal to the invariant 1-d subspace is carrying the full representation.

So let 2n be the even dimensional case. There exists the set of antisymmetric unit matrices $$(L_{(i,k)})_{m,n} = \delta_{m,i}\delta_{n,k}-\delta_{n,i}\delta_{m,k}$$

e.g.

$$L_{1,2}\ = \ \left(

\begin{array}{cccc}

0 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

\end{array}

\right) , \quad L_{1,2}^2 \ = \ \ \left(

\begin{array}{cccc}

-1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

\end{array}

\right) $$

Any such matrix generates a rotation matrix $O_{ik}(\alpha_{ik})$, leaving all direction inavariant except the 2d-plane $(x_i,x_k)$

by

$$(e^{\alpha_{ik} L_{(i,k)}})_{mn}= 1 + (\cos (\alpha_{ik}) -1) \ \delta_{im}\ \delta_{kn} + (\alpha_{ik} L_{(i,k)})_{mn} \sin (\alpha_{ik}) $$

because the even powers generate an alternating unit diagonal matrix with two entries only

$$ \left(\left(L_{(i,k)}\right)^2\right)_{m n} \ = \ -\delta_{im}\ \delta_{kn} $$

It follows, that the 2n-dimensional orthogonal matrix is generated by all products of all 2-d rotation matrices in any order. In the vincinity of the unit matrix the linear approximation is given by

$$O(\mathbf \alpha) = 1 + \sum_{1<i<k<2n}\alpha_{ik} L_{ik} + \mathrm o\left( \mathbf \alpha^{\otimes 2}\right)$$

that extends to the exponential by the group identity

$$\lim_{s\to \infty} \ \left(1 + \frac{1}{s}\ \sum_{1<i<k<2n}\alpha_{ik} L_{ik} \right)^s \ = \ e^{\sum_{ik} \ \alpha_{ik} \ L_{ik}}$$

Such general rotations are entangled in such a way, that finally only the formula for the determination of the rotation angle in any 2-plane by taking the trace with the generator for that plane yields the well known $\cos$-formula in dimension 2

$$2 \cos(\alpha) \ = \ Tr\left(\begin{array}{cc} \cos \alpha & -\sin \alpha \\ \sin \alpha & \cos \alpha \end{array} \right)$$