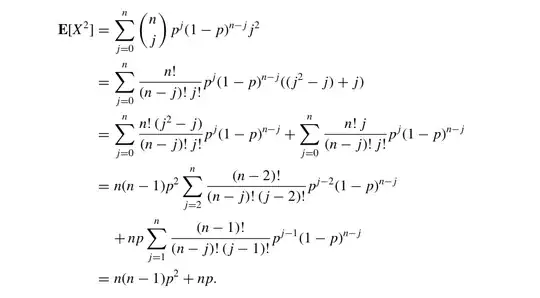

Well, you could try the elementary approach:

$$\mathrm{Var}[X] = \mathbb E\left[X^2\right] - \mathbb E[X]^2,$$

where $\mathbb E[X] = np$ and $\mathrm{Var}[X] = np(1-p)$. So

$$\mathbb E\left[X^2\right] = \mathrm{Var}[X] + \mathbb E[X]^2= np(1-p) +(np)^2=np(1-p+np)= n(n-1)p^2 + np$$

Quick proof for expectation and variance:

Let $Y_i \overset {\text{i.i.d.}} \sim \mathrm{Bern}(p)$, then

$$\mathbb E[X] = \mathbb E\left[\sum_{i=1}^n Y_i\right] = \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbb E[Y_1] = np$$

$$\mathrm{Var}[X] = \mathrm{Var} \left[\sum_{i=1}^n Y_i\right] \overset {Y_i\text{ i.i.d.}} = n \:\mathrm{Var}[Y_1] = np(1-p),$$

as $\text{Var}[Y_1]= p - p^2$:

$$\mathbb E[Y_1^2] = 1^2 \cdot p + 0^2 \cdot (1-p) = p=\mathbb E[Y_1]$$

But the most elegant solution would be using MGFs:

The Momentgenterating Funktion (MGF) of a RV X is defined as:

$$M(t) =\mathbb E[e^{tX}]$$

It is easy to show that for $Y_i$ $\text{i.i.d.}$ and $X:=\sum_{i=1}^n Y_i$

$$M_X(t) =\mathbb E[e^{tX}]= \mathbb E[e^{tY_1}]^n$$

So for $Y_i \overset{\text{ i.i.d.}}{\sim} \mathrm{Bern}(p)$ we have:

$$M_Y(t)=\mathbb E[e^{tY_1}] = p e^{t} + (1-p)$$

$$\implies M_X(t)= [p e^{t} + 1-p]^n$$

Now the $n$-th moment is the $n$-th derivation of $M(t)$ evaluated at $t=0$ (verify this fact by using the Taylor-series expansion of the exponential function $\exp(tX) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac {t^nX^n} {n!}$), so:

$$M'(t)= n[p e^{t} + 1-p]^{n-1} p e^{t} \implies M'(0) = n[p e^{0} + 1-p]^{n-1} p = np =\mathbb E[X]$$ (works)

$$M''(t)= n(n-1)p^2[p e^{t} + 1-p]^{n-2} e^{t} + M'(t)\implies M''(0) = n(n-1)p^2 + np = \mathbb E[X^2]$$ (also works)

$\dots$

You see, now you have a pattern for all moments, and you didn't even need to solve complicated binomial coefficients ;-)

(Thanks to @Egor Ivanov for caring about my Tex-Skills <3, your edit was lost upon updating this post...)