Hyperbolic case

First off, the combinatorics of tilings in hyperbolic geometry will also affect the size of the cells. So I'd guess a hyperbolic bee might be more interested in having approximately bee-sized cells, even if it means using slightly more wax. But that's a question for hyperbolic biology, so back to the geometry.

The way you quoted it, you'd be minimizing line length per number, which has a length unit remaining. Thus the optimum is not invariant under scale. But the video mentions that the cells should have unit area. So if you had a honeycomb with cells of area 9 square length units, you'd scale it down by 3 length units and then start measuring edge lengths. Or in other words, you are minimizing perimeter divided by the square root of the enclosed area. You could as well square that and minimize squared perimeter divided by enclosed area. If you care about absolute numbers, particularly comparing them with the limit process described in the video, you might want to divide the perimeter by two since each wall is shared by two adjacent cells, so the contribution per cell is just half of that. But for the sake of finding the optimum it does not matter.

Let's consider a regular hyperbolic tiling of $n$-gons, $m$ of them meeting at each corner, with $\frac1m+\frac1n<\frac12$. What's its edge length? The hyperbolic law of cosines for curvature $-1$ states

$$\cosh a=\frac{\cos\alpha+\cos\beta\cos\gamma}{\sin\beta\sin\gamma}$$

Now consider a right triangle covering $1/2n$ of your cell. It has $\alpha=\frac\pi n$ at the center, $\beta=\frac\pi m$ at the vertex and $\gamma=\frac\pi 2$ at the center of the edge of the cell. This leads to

$$a=\operatorname{arcosh}\frac{\cos\frac\pi n}{\sin\frac\pi m}$$

The area of that triangle is equal to the angle defect:

$$A=\pi-\frac\pi n-\frac\pi m-\frac\pi 2=\pi\left(\frac12-\frac1n-\frac1m\right)$$

Now the whole cell is composed of $2n$ such triangles, so the total perimeter is $2na$ and the total area is $2nA$. Thus the number to optimize is

$$\frac{(2na)^2}{2nA}=\frac{2n\left(\operatorname{arcosh}\frac{\cos\frac\pi n}{\sin\frac\pi m}\right)^2}{\pi\left(\frac12-\frac1n-\frac1m\right)}$$

Now you can try this out for some values of $m$ and $n$:

$$\begin{array}{c|ccccccc}

n\backslash m & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 & 9 \\\hline

3 & & & & & 23.8496 & 26.7747 & 29.5759 \\

4 & & & 20.0136 & 23.7379 & 27.2316 & 30.5319 & 33.6653 \\

5 & & 17.9257 & 22.5929 & 26.8885 & 30.8947 & 34.6616 & 38.2245 \\

6 & & 19.8745 & 25.2172 & 30.1103 & 34.6579 & 38.9226 & 42.9479 \\

7 & \mathbf{15.0035} & 21.8342 & 27.8626 & 33.3653 & 38.4677 & 43.2445 & 47.7470 \\

8 & 16.1524 & 23.7997 & 30.5195 & 36.6382 & 42.3027 & 47.5994 & 52.5871 \\

9 & 17.3024 & 25.7687 & 33.1832 & 39.9220 & 46.1528 & 51.9740 & 57.4518

\end{array}$$

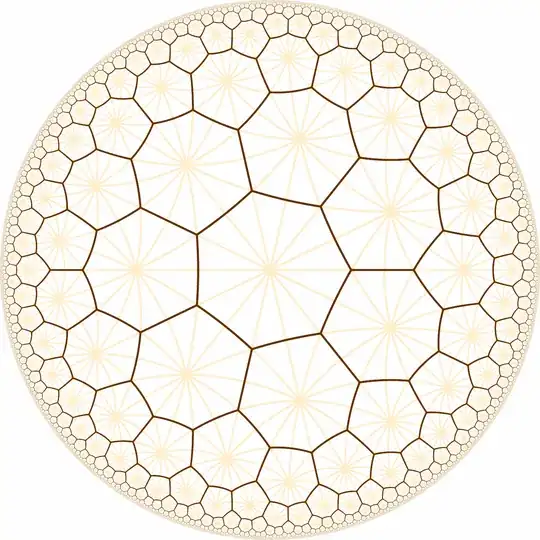

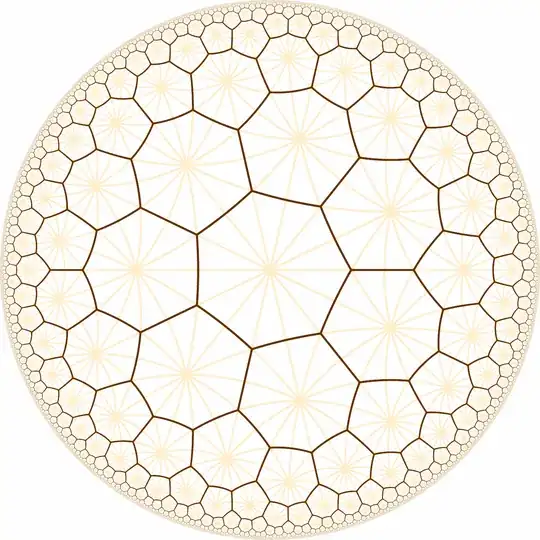

It turns out the optimum is the 7,3 tiling: regular heptagons, three of them meeting at each vertex. This is also the tiling with the smallest cells, so if the cells aren't too small for our hyperbolic bees, they should pick this one. For comparison, the Euclidean hexagon is at $8\sqrt3\approx13.8564$, the Euclidean square at $16$. So that hyperbolic heptagonal tiling is still better than the Euclidean 4,4.

Elliptic case

You also asked for the elliptic case, and there the approach is pretty much the same. Use the spherical law of cosines and the surplus angle as a measure of area and you get

\begin{gather*}

a = \arccos\frac{\cos\alpha-\cos\beta\cos\gamma}{\sin\beta\sin\gamma}

= \arccos\frac{\cos\frac\pi n}{\sin\frac\pi m}

\\

A = \frac\pi m+\frac\pi n+\frac\pi 2-\pi = \pi\left(\frac1m+\frac1n-\frac12\right)

\\

\frac{(2na)^2}{2nA}=\frac{2n\left(\arccos\frac{\cos\frac\pi n}{\sin\frac\pi m}\right)^2}{\pi\left(\frac1n+\frac1m-\frac12\right)}

\end{gather*}

But here the degenerate situations win out. For $m=2$ you get two hemispheres no matter the value of $n$, which is already better than any $m>2$. For $m=1$ you get a division by zero since $\sin\frac\pi m=0$ in that case. But you can well imagine that considering the whole sphere a single cell is optimal as it uses no walls at all.