To me, this question (as well as the many up-votes it received) implied to me that it is appropriate to consider an integral to be a sum of $\beth_1$-many terms. I assume that when one starts to consider the integral with the surreal numbers in mind, it is no longer mathematically unrigorous to view it as an infinite sum of various values times an infinitesimal change in a variable.

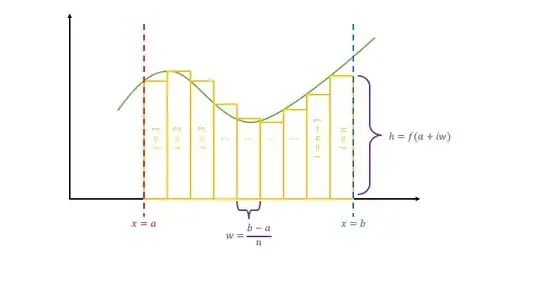

I don’t pretend to have formal knowledge of set theory, but, using the definition of the integral shown below and the definition that $\varepsilon = \left\{ 0 \,\middle|\, \frac12 , \frac14 , \frac18 , \cdots \right\}$ is an infinitesimal surreal number greater than $0$ but less than any real number, consider this transformation of the integral from real to surreal.

$$\begin{align} \int_\limits{[a,b]} f(x) \, dx &= \lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^{n}h \cdot w \\ &= \lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^{n} f\left(a+iw\right) \cdot \frac{b-a}{n} \\ &= \lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^{n} f\left(a+i\frac{b-a}{n}\right) \cdot \frac{b-a}{n} \\ \end{align}$$

Formulation

Take the above definition and drop the limit and and balance this with infinitesimal and transfinite surreal numbers.

As $n\to\infty$, the width of Riemann rectangles $w$—or alternatively $\Delta x$—approaches the tiny sliver of the $x$-axis that we write as $dx$. This ‘infinitesimal’ $dx$ is equal in size to $\varepsilon$.

Furthermore, as $n\to\infty$, the sum becomes a sort of series. When dealing with real numbers, we allow sums that have a number of terms equal to a natural number, even if the number of terms approaches the upper bound of the natural numbers (since the natural numbers are just as infinite as the number of terms in the sum). When dealing with the surreal numbers, let us allow a sum that has a number of terms equal to a transfinite cardinal: $\beth_1$. (Here $\beth_1$ appears as opposed to $\beth_0$ because the indexed domain became a continuous interval as $n\to\infty$. You could also quaintly think to yourself that integrals need more ‘infiniteness’ than do series to compensate for their infinitesimal terms.) If we allow this, we can then index the sum for all $i\in[a,b]$ and in turn evaluate $f$ at all of these $i$ as opposed to at each $a+iw$.

$$\lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^{n} f\left(a+iw\right) \cdot w = \sum_{i\in[a,b]} f(i) \cdot \varepsilon$$

Now we can certainly see how this resembles an integral. Devise a new symbol $\int$ that denotes continuous summation as opposed to $\sum$ which denotes summation over discrete values, change $\varepsilon$ to $dx$ and make the independent variable consistent throughout the entity, and you get

$$\sum_{i\in[a,b]} f(i) \, \varepsilon = \int\limits_{[a,b]}f(x) \, dx$$

Concessions

I know that in reality when $w$ is taken by itself, $\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{b-a}{n}=0$, but I didn’t know how to pull the limit into the sum and make this transformation rigorously. Nevertheless, most mathematicians will agree that $dx$ is not there to represent $0$.

In fact, I know that there is arguably more than one instance in which a ‘definition’ I provided was less than rigorous. However, this is my objective: to reconsider what an integral is considered by utilizing the surreal numbers as tools.

Questions

- What are both the strengths and the weaknesses of this reformulation as a ‘proof’ or persuasive argument of sorts? Overall, is it valid?

- If it is valid, could there ever be any way to evaluate a series with $\beth_1$ surreal terms in the way that we can evaluate a series with $\beth_0$ real terms?

Because part of my question is about the weakness of this argument, I will not change any errors that are pointed out to me. That way, they can be referenced in an answer. For this same reason, please don’t edit this question so as to correct an inaccurate assertion; simply draw attention to it in an answer or comment.

Edit 02:35 31 Jul 17: Example

The very kind @ProfessorVector suggested that I provide an example of how to evaluate these integrals. While I can’t confidently try my hand at any arithmetic with surreals, I can give an example of the $\lim\sum$ definition applied to $x^2$ over $[1,2]$:

$$\begin{align} \lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^{n} f\left(a+i\frac{b-a}{n}\right) \cdot \frac{b-a}{n} &= \lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{2-1}{n} \left(1+i\frac{2-1}{n}\right)^2 \\ &= \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( 1 + \frac{2i}{n} + \frac{i^2}{n^2}\right) \\ &= \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{1}{n} \left( \sum_{i=1}^{n}1 + \sum_{i=1}^{n}\frac{2i}{n} + \sum_{i=1}^{n}\frac{i^2}{n^2} \right) \\ &= \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{1}{n} \left( n + \frac{2}{n}\frac{n(n+1)}{2} + \frac{1}{n^2}\frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{6}\right) \\ &= \lim_{n\to\infty} \left( 2 + \frac1n + \frac13 + \frac{1}{2n} + \frac{1}{6n^2} \right) \\ &= 2+0+\frac13+0+0 \\ &= \frac73 \\ \end{align}$$

(I skipped over the expansions and reductions of the polynomials.) Notice that I have to make use of prescribed formulae for evaluating sums. I imagine that this is the barrier to evaluating some $\sum_{i\in[a,b]}f(i)\,\varepsilon$.