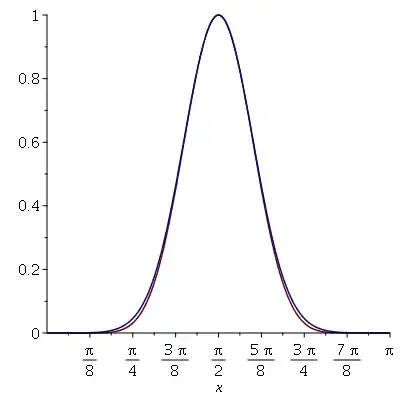

One thing that obscures the point in this exercise is that as $k$ increases, the Gaussian curve $y = \exp\left(-\frac k2(x-\frac\pi2)^2\right)$

develops a very narrow peak in the curve near $x=\frac\pi2$ surrounded by tails that are nearly zero.

As long as the values of $\sin^x(x)$ are close enough to

$\exp\left(-\frac k2(x-\frac\pi2)^2\right)$ near the very narrow top of the peak, the slope along the sides of the peak ($y$ values between $0.2$ and $0.9$ or other suitable bounds) becomes so steep that you could have a vertical error of several percent and the graphs would still appear very close because of the small horizontal distance to the nearest point on

the other curve.

As it turns out, the approximation is really quite good, but it's hard to be sure just by looking at these graphs.

I think we get a better-controlled comparison when we compare all of the approximations to the same Gaussian.

To make things a little simpler, I suggest first shifting the graph left so that it is centered on the line $x=0$ instead of $x=\frac\pi2.$

After this shift, we would be comparing $\cos^x(x)$ with

$\exp\left(-\frac k2 x^2\right).$

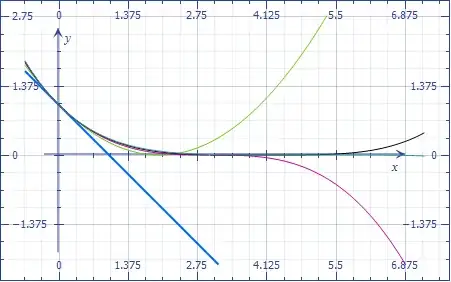

Next, we expand the graph in the horizontal direction by a factor

of $\sqrt k.$ That is, we substitute $\frac x{\sqrt k}$ for $x.$

The Gaussian function then is $\exp\left(-\frac12 x^2\right).$

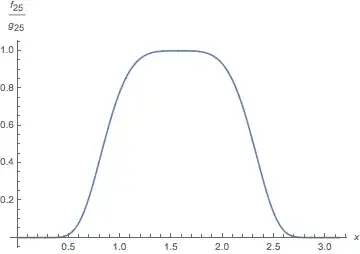

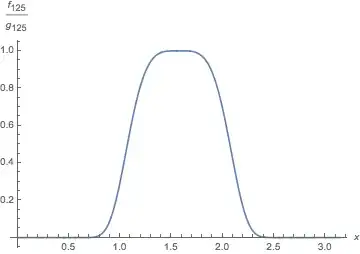

So we now will be comparing the sequence of sinusoidal functions

$h_k(x) = \cos^k\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt k}\right)$ with the

Gaussian $f(x) = \exp\left(-\frac12 x^2\right).$

Plotting both $f$ and $h_k$ on the same graph, it is clear that $h_k$ approximates $f$ reasonably well over a wide interval for moderately large values of $k$. (For any particular $k,$ of course, $h_k$ will take the value $1$ at infinitely many values of $x,$ but as $k$ increases the gap between these values of $x$ increases.)

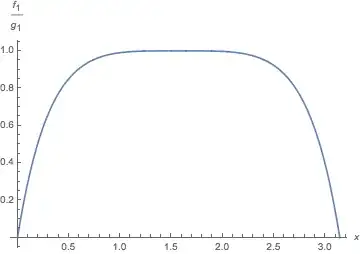

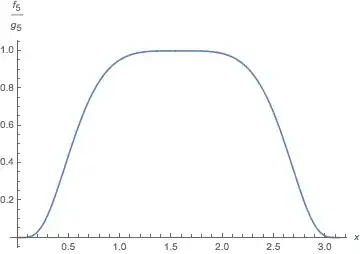

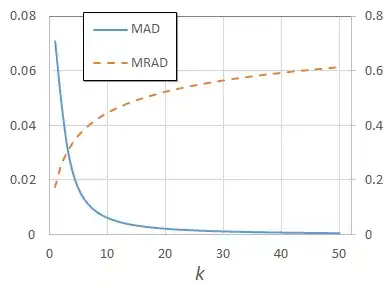

Moreover, if we consider the relative error $\frac{h_k}{f} - 1,$

it is visually close to zero for $-\frac12 < x < \frac12$ even for $k=1,$

and the "flat" part of the curve $\frac{h_k}{f} - 1$ gets wider as $k$ increases.

For example, consider this Wofram Alpha graph.

It shows that the error of $h_{100}$ relative to $f$ is less than half a percent when $-1.5 < x < 1.5.$

Taking a hint from

Semiclassical

and Claude Leibovici,

let's consider the Taylor series of these functions. The Taylor series of

$\exp\left(-\frac12 x^2\right)$ is

$$

f(x) = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^4}{8} - \frac{x^6}{48} + \mathcal O(x^7).

$$

The Taylor series of $\cos^k\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt k}\right)$ is

$$

h_k(x) = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2} + \left(\frac18 - \frac{1}{12 k}\right) x^4

- \left(\frac1{48} - \frac1{24k} + \frac1{45k^2}\right) x^6

+ \mathcal O(x^7).

$$

It's clear that for any $x,$ at least the first two terms of the difference

$$

f(x) - h_k(x) = \frac{1}{12 k} x^4

- \left(\frac1{24k} - \frac1{45k^2}\right) x^6 + \mathcal O(x^7)

$$

disappear as $k \to\infty$; it seems that the other terms disappear as well.