In an ellipse, all circumscribed parallelograms whose sides are parallel to a pair of conjugate diameters have the same area. And it is easy to show that any other parallelogram circumscribed to the same ellipse has a greater area.

Proof.

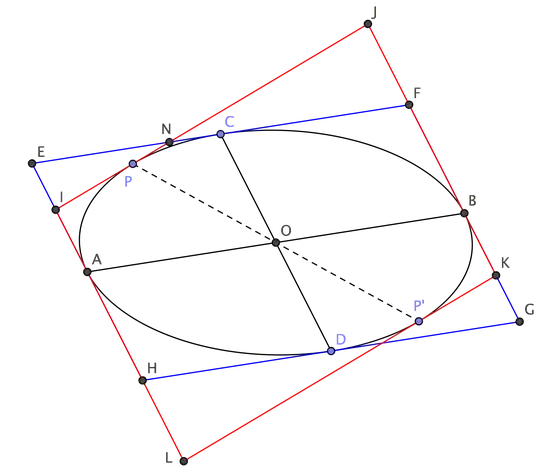

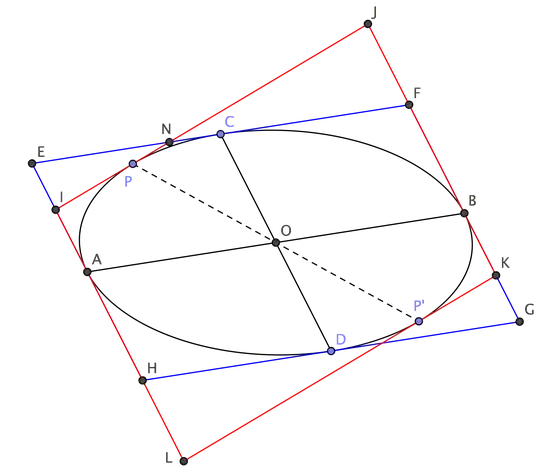

Consider (diagram below) parallelogram $EFGH$, whose sides are tangent to the ellipse and parallel to conjugate diameters $AB$ and $CD$. Take any other diameter $PP'$: tangents at its endpoints form with lines $FG$, $HE$ another parallelogram $IJKL$, circumscribed to the ellipse. As line $IJ$ cuts $EF$ at $N$, the difference between the areas of $IJKL$ and $EFGH$ is equal to twice the difference between the areas of triangles $JFN$ and $IEN$. But $C$ is the midpoint of $EF$ and $N\ne C$, so that outer triangle $JFN$ is larger than inner triangle $IEN$. It follows that parallelogram $IJKL$ is larger than $EFGH$.

In particular, among all parallelograms whose sides are parallel to a pair of conjugate diameters, we can consider the rectangle whose sides are parallel to the ellipse axes of symmetry: by the above proof, it is the smallest rectangle circumscribed to the ellipse.

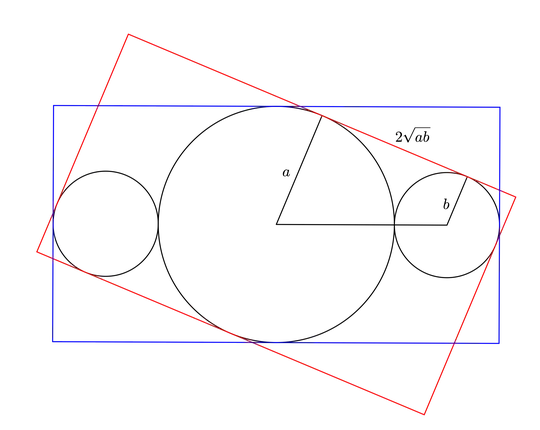

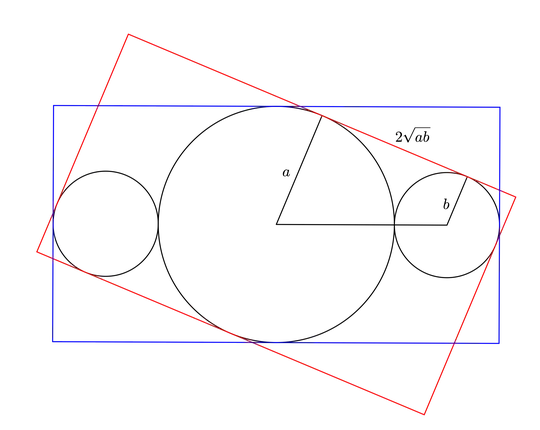

But it is not true, in general, that if a closed curve has two orthogonal axes of symmetry, then the circumscribed rectangle with minimum area has the same symmetry. Consider for instance the curve formed by the three circles in the diagram below. Red rectangle has area $4a(2\sqrt{ab}+b)$ while blue rectangle has a larger area of $4a(a+2b)$.