Your teacher was referring to a true fact that is worthwhile for you to know,

although as it turns out, it does not apply to your two calculations.

To understand what your teacher is talking about, we need to remember

that $\int f(x)\,dx$ does not describe a single function, but rather a

family of functions containing every function whose derivative is $f.$

Each member of that family of functions is an antiderivative or

primitive of $f.$

Since the notation for a family of functions like this is a bit complicated,

we usually indicate the solution of an indefinite integral by writing

down just one of its antiderivatives, that is, one representative from the family of functions that solves

the integral. The $+C$ term is an acknowledgement that the choice of which function to write is arbitrary; it says that in order to say which

of the antiderivatives of $f$ we have written, we just have to choose a value for the constant $C.$

A different choice will give us a different antiderivative, but it belongs to the same family of functions.

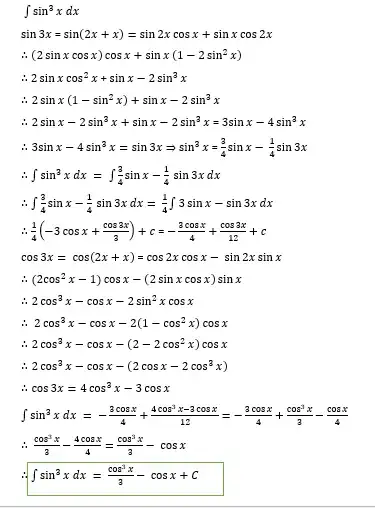

It often happens that when you use two different methods to integrate a function, you end up with answers that look different,

in much the same way that your two answers look different.

In those cases, your teacher is correct: if you remove the $+C$ from each answer, the functions that remain differ by a constant amount, and that is the difference your teacher referred to.

An example of this is in this answer to another integration question

In a definite integral of $f,$ again we can use any antiderivative of $f$

in the solution, but we must use the same antiderivative at both

ends of the interval of integration.

So whatever the amount is by which the antiderivative you chose is greater than the antiderivative someone else chose, the difference cancels out

when you subtract the value at one end from the value at the other.

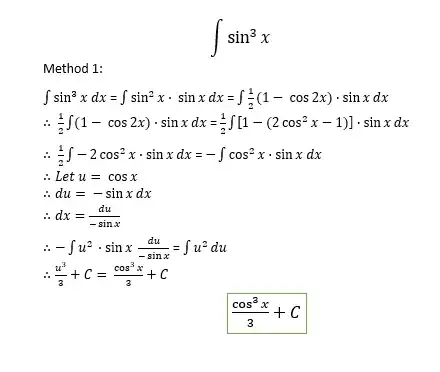

In your particular integral, however, in your first

attempt at the solution you simplified $[1 - (2\cos^2 x - 1)]$

to $-2\cos^2 x.$ That is incorrect. In fact,

$$[1 - (2\cos^2 x - 1)] = 2 - 2\cos^2 x.$$

The missing term $2$ is why you are missing the term $-\cos x$ at the end.

That is, your first result is simply wrong, not just using a "different constant $C$" than your second result.