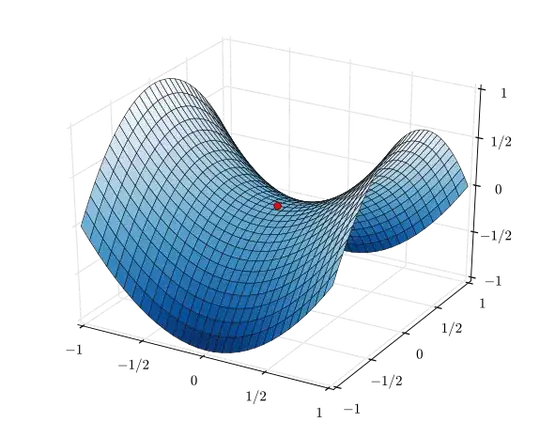

Assume a function similar to a saddle, like this.

At the origin, the gradient will be 0. However, assume you have a function similar to this one where the gradient of the saddle at the origin is not 0.

Then obviously, the magnitude of the direction of maximum increase is either in the x direction or in the y direction. However, if you add up those two vectors, which is taking the gradient of this function, you get a vector going sideways, which is not in the direction of maximum increase.

So, this is confusing me. The vector addition of the rate of increase the x direction and the rate of increase in the y direction does not equal the direction of highest increase.