I'm not sure what order material is covered in the book you're referencing, but here's a fairly elementary demonstration that $H^1_{dR}(\mathbb{R}^2\setminus\{(0,0)\} \cong \mathbb{R}.$ It requires only material covered in a standard American Calc 3 class, together with basic facts about forms. For ease of writing, I'll write $M$ for $\mathbb{R}^2\setminus \{(0,0\}$.

Proposition 1: For $\eta = P(x,y) dx + Q(x,y) dy$, $\eta$ is closed iff $P_y = Q_x$. Said another way, $\eta$ is closed iff the integrand you get in Green's theorem vanishes.

Proof: Well, since $dx\wedge dx = 0$ $d(Pdx) = P_y dy\wedge dx$. Likewise, $d(Qdy) = Q_x dx\wedge dy$, so $d\eta = (-P_y + Q_x) dx \wedge dy$. The result follows.

Now comes the technical result. In some sense, Proposition 2 is proving that $H^1_{dR}(M)$ is at most an $\mathbb{R}$ because there is only one obstruction to being exact: $\int_C \eta = 0$.

Proposition 2 Suppose $\eta = Pdx + Qdy$ is a smooth $1$-form on $M$. Let $C$ denote the unit circle with center $(0,0)$ traversed counter clockwise. Assume $\eta$ is closed. Then $\eta$ is exact iff $\int_C \eta = 0$.

Proof: Before proving this, the hypothesis that $\int_C \eta = 0$ implies that $\int_{C_R} \eta =0$ for any circle of radius $R$ centered at $(0,0)$. Indeed, because $\eta$ is closed, $P_y - Q_x = 0$. Thus, by Green's theorem, we have $\int_C \eta - \int_{C_R} \eta = \iint_X P_y - Q_x dA$ where $X$ is the annulus between $C$ and $C_R$. Since $\int_C\eta = 0$ and $P_y - Q_x = 0$, $\int_{C_R}\eta = 0$. With this out of the way, we can now actually prove this proposition.

First, assume $\eta$ is exact: $\eta = df$ for some smooth function $f$. We paramaterize $C$ as $(x,y) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ with $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$. Writing $f(x,y) = f(\cos t, \sin t) = g(t)$ for some smooth function $g$, we then compute $$\int_C df = \int_0^{2\pi} d(f(\cos t, \sin t)) = \int_0^{2\pi} dg = \int_0^{2\pi} g'(t) dt = g(t)|_0^{2\pi} = f(\cos t, \sin t)|_0^{2\pi} = 0.$$ Thus, if $\eta = df$, then $\int_C \eta = 0$.

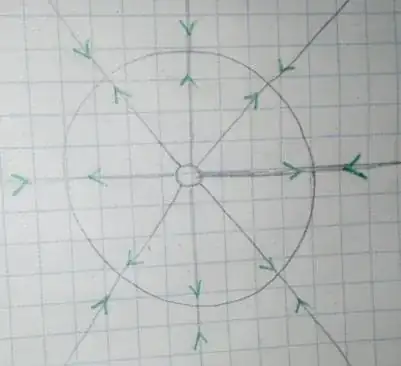

Now, let's prove the converse, so assume that $\int_C \eta = 0$. We define a function $f:M\rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ with $df = \eta$ as follows. For $p\in M$ which is not on the negative $x$-axis, let $L_p$ denote the segment connecting the point $(1,0)$ to $p$ (which stays in $M$. For $p\in M$ off of the negative $y$-axis, let $B_p$ a line segment connecting $(1,0)$ to $(0,1)$ followed by a segment connecting $(0,1)$ to $p$. For $p$ off of the positive $y$-axis, let $D_p$ be the line segment connecting $(1,0)$ to $(0,1)$ followed by the segment connecting $(0,1)$ to $q$.

For $p\in M$ note that at least 2 out of three of $L_p$, $B_p$, and $D_p$ are defined. We claim that $\int_{L_p} \eta = \int_{B_p} \eta$ if both are defined. Specifically, drawing both $L_p$ and $B_p$, it's clear they make a (possible degenerate) triangle which does not contain $(0,0)$. Applying Green's theorem, togther with Proposition 1 (and recalling that $\eta$ is closed) shows $\int_{L_p} \eta = \int_{B_p} \eta$. The same proof works for showing $\int_{L_p}\eta = \int_{D_p}\eta$ (again, assuming both are defined).

To see that $\int_{B_p} \eta = \int_{D_p} \eta$ (assuming both are defined), let $R$ be a large enough so that $B_p \cup D_p$ lies inside the circle of radius $R$ centered at $(0,0)$. Applying Green's theorem to the region between $B_p\cup D_p$ and $C_R$, we deduce that $\int_{B_p} \eta - \int_{D_p}\eta + \int_{C_R} \eta = 0$. Since, we have already showed $\int_{C_R} = 0$, it follows that $\int_{B_p}\eta = \int_{D_p} \eta$.

Now, let's first prove that $f_x(p) = P(p)$. For $h$ small, let $S_h$ be the line segment connecting $p$ to $p + (h,0)$. If $p$ is not along the negative real axis, then the three paths $L_p$, $S_h$, and $L_{p+(h,0)}$ are defined and form a triangle. Again applying Green's theorem, we see that $ \int_{L_{p+(h,0)}} \eta -\int_{L_p}\eta =\int_{S_h} \eta$. Paramaterizing $S_h$ via $(x,y) = p + (t,0)$, we see $y' = 0$, so \begin{align*} f_x(p) &= \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{f(p+(h,0)) - f(p)}{h}\\ &= \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{\int_{S_h} \eta}{h}\\ &= \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{\int_0^h P dx}{h} \\&= P(p),\end{align*} where the last line uses L'Hospital's rule together with the fundamental theorem of calculus. If, on the other hand, $p$ is along the negative real axis, repeat this proof with $D_p$ and $D_{p + (h,0)}$ replacing $L_p$ and $L_{p+(h,0)}$.

The proof that $f_y(p) = Q(p)$ is almost identical. In fact, if $p$ is not on the negative real axis, again use $L_p$ and $L_{p+(0,h)}$. If $p$ is on the negative real axis, to show $\lim_{h\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{f(p+(0,h)) - f(p)}{h} = Q$, use $B_p$ and $B_{p+(0,h)}$, and to show that $\lim_{h\rightarrow 0^-} \frac{f(p+(0,h)) - f(p)}{h} = Q$, use $D_p$ and $D_{p+(0,h)}$.$\square$

Now, let $\omega = \frac{-y}{x^2 + y^2}dx + \frac{x}{x^2+y^2}dy.$ Computing $P_y$ and $Q_x$ both gives $\frac{x^2-y^2}{(x^2 + y^2)^2}$, so they're equal. Hence, by Proposition 1, $\omega$ is closed.

Proposition 3: The form $\omega$ is not exact.

Proof: From proposition $2$, it's enough to compute $\int_C \omega$ where $C$ is the unit circle centered at $(0,0)$. Paramaterizing the circle via $(x,y) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ with $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$, we get $\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{-\sin t}{\cos^2 t + \sin^2 t} (-\sin t) dt + \frac{\cos t}{\cos^2 t + \sin^2 t}(\cos t) dt = \int_0^{2\pi} (\sin^2 t + \cos^2 t)dt = 2\pi$. Since $2\pi \neq 0$, $\omega$ cannot be exact. $\square$

If follows that $[\omega]\in H^1_{dR}(M)$ is non-zero.

Proposition 4: Suppose $\eta$ is a closed one form. There is a real number $\lambda$ with the property that $\lambda \omega - \eta$ is exact. In other words, $[\eta] = \lambda[\omega]$ so $[\omega]$ generates all of $H^1_{dR}(M)$.

Proof: Let $\lambda = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_C \eta$, where $C$ is the unit circle centered at $(0,0)$. Then \begin{align*}\int_C \lambda \omega - \eta &= \lambda \int_C \omega - \int_C \eta\\ &= \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_C \eta \int_C \omega - \int_C\eta\\ &= \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_C \eta 2\pi - \int_C\eta\\ &= 0.\end{align*} Since $\lambda \omega - \eta$ is obviously closed, Proposition 2 now implies that $\lambda \omega - \eta$ is exact. $\square$